Vase is first evidence of a real gladiator fight in Roman Britain

LONDON – Elaborately armed, two gladiators named Memnon and Valentinus faced each other in brutal combat almost 2,000 years ago.

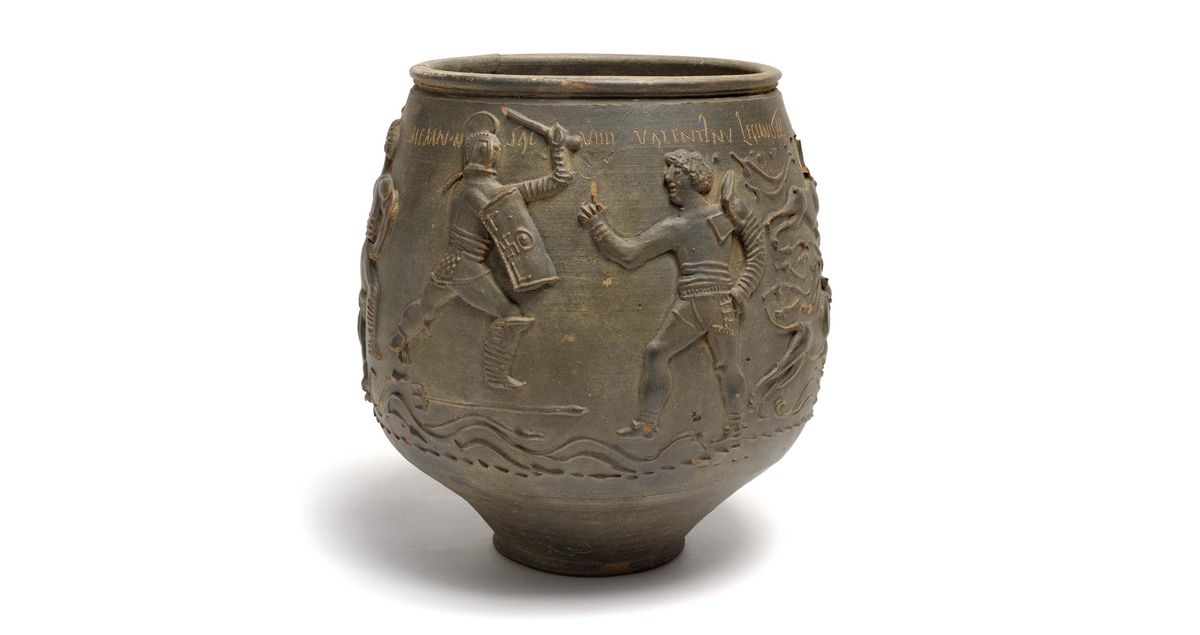

Historians have known since a clay vessel was discovered in 1853 that Memnon, an enslaved past champion who experts say was probably Black, won this match. Valentinus, also enslaved, can be seen raising an index finger toward the sky, a gladiatorial gesture of submission equivalent to the waving of a white flag.

But unknown until now was where the match took place: Colchester, England.

Archaeologists say it is the only depiction of a real gladiator match that took place in Roman Britain. While there are other artifacts suggesting that gladiators were in Britain, on the outer reaches of the empire in its heyday, none depicted specific matches taking place.

An analysis conducted by archaeologists collaborating across British universities reveals that the two gladiators almost certainly met for combat near where the pot was found – a city in what’s now the eastern county of Essex.

“When you now look at this vase, you know that you’re seeing real people on it. They fought here, in Colchester,” which was known to the Romans as Camulodunum, Glynn Davis, a senior curator at Colchester Museums, said in a telephone interview Monday. The vase is believed to date to the late second century.

“It was a revelation,” he said.

Because of the sophistication of the frieze, archaeologists previously assumed that the pot had been imported from elsewhere in the Roman Empire.

Archaeologists studying the lettering scratched onto the pot’s surface and its clay material concluded that the description was carved while the clay was still soft before it was fired in a Colchester kiln. That means, according to Davis, that Memnon and Valentinus met for battle nearby.

“The clay is like a fingerprint for where it’s been made,” said Davis, who worked alongside a team of experts to examine its composition. “It matched identically with the local clay.”

A separate analysis of the Latin lettering inscribed across the pot’s surface found that Memnon and Valentinus’ story was spelled out before the pot entered the kiln and not scratched onto the surface later.

“We were looking at an inscription that couldn’t have been scratched on after firing,” he said. “The T’s and the X’s you can only achieve in soft clay. If you tried to do that in fired clay – it would chip.”

The researchers concluded that the vase was commissioned, designed and fired locally, upending previous assumptions that it had been imported from elsewhere in Europe or that it may have been manufactured as a generic with details added afterward. “This can’t have been a generic souvenir,” Davis said.

Memnon had a heavy advantage in the fight, according to the vase’s depiction. He carried a sword and a large shield and had a helmet that completely encased his head except for eyeholes, considerably better than his rival’s weaponry and armor. The inscription says this was his ninth victory as a gladiator.

It is also highly likely that he was Black, said King’s College London archaeologist John Pearce, who was involved in the research. Memnon, probably a stage name, is an apparent reference to the King of the Ethiopians in Homer’s Troy, Pearce said. The mythological figure recurs throughout Roman literature and is frequently accompanied by a reference to his ethnicity or that of his companions.

“It seems to us plausible that the choice of name for this particular gladiator was influenced not only by his martial abilities but also by his skin color,” Pearce said via email. “He could be a star performer brought a long distance or could himself have been born in Britain to parents from places far to the south who had come to the province as forced or willing migrants.

“Inscriptions and increasingly analysis of human skeletal remains show us the presence of individuals of Middle Eastern and African geographical origin in Roman period Britain, especially in the province’s cities.”

The vase shows Valentinus, Memnon’s rival who appears to have been left-handed, armed with just a trident that has dropped to the ground. He wears only a padded sleeve and shoulder guard for protection.

Not shown on the pot, according to Pearce, is the match’s referee – who would have been gesturing to Memnon to pause combat until the fight’s sponsor decided whether to order the defeated combatant to be shown mercy or slain.

The crowd may have influenced that decision, cheering on behalf of the defeated gladiator if he had fought well – or encouraging Memnon to kill him. One thing we still don’t know: Valentinus’ fate.