Weathercatch: How the weather impacted – and was impacted by – the eruption of Mount St. Helens

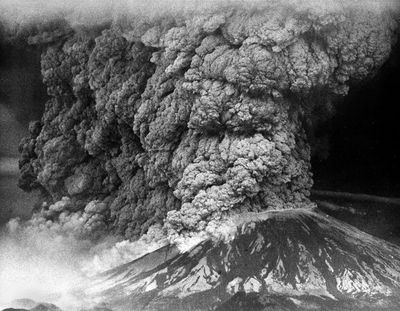

If you were in the Pacific Northwest 43 years ago Thursday, there’s a good chance you remember hearing the news: Mount St. Helens erupted in Washington, blowing the mountaintop apart and shooting a huge cloud of ash more than 12 miles into the sky.

The disaster on Sunday, May 18, 1980, killed 57 people and decimated 230 square miles of landscape. The towering ash plume drifted east, blocking out the sun for miles.

“Death is everywhere,” the Oregonian newspaper wrote. “The living are not welcome.”

But the weather always lives on. Sunny skies that morning enabled satellites to capture clear images of the ash cloud’s movement, pushed by the winds.

After the eruption, an upper-level wind carried a big part of the volcanic ash cloud to the east-northeast at about 60 mph, according to U.S. Geological Survey reports. Two inches of ash fell on the city of Yakima within an hour. Two hours later, the plume reached Spokane, followed by North Idaho 15 minutes afterward.

“Over the course of the day, prevailing winds blew 520 million tons of ash eastward across the United States and caused complete darkness in Spokane, Washington, 250 miles from the volcano,” the USGS reported.

By the next morning, winds had carried the diffused ash cloud across 17 states. Within two weeks, particles of fine ash circled the earth.

Not only did the weather influence the eastward dispersion of the volcanic ash, but the eruption temporarily changed our region’s weather. Surprised? Read on.

The dense ash cloud blocked the sun as it moved across portions of Eastern Washington that day, causing temperatures to drop by about 14 degrees. That night, however, the low-level sunlight-absorbing cloud caused temperatures to rise by roughly 12 degrees.

Fortunately, the eruption’s impact on our weather was short-lived – but not its impact on science. Amid the devastation, Mount St. Helens became a hotbed of study on volcanic activity and improved monitoring, weather impacts following an eruption, and the surprising ways that surrounding landscapes can recover.

Nic Loyd is a meteorologist in Washington state. Linda Weiford is a writer in Moscow, Idaho, who’s also a weather geek.