Louis Gossett Jr., commanding actor of TV and film, dies at 87

Louis Gossett Jr., an actor who brought authority to hundreds of screen roles, winning an Oscar as a Marine drill instructor in “An Officer and a Gentleman” and an Emmy Award as a wise, older guide to the enslaved Kunta Kinte in the groundbreaking miniseries “Roots,” died Friday at a rehabilitation center in Santa Monica, California. He was 87.

His first cousin, Neal L. Gossett, confirmed the death but said he did not know the immediate cause. In recent years, Louis Gossett Jr. battled prostate cancer and respiratory illness caused by toxic mold in his former home in Malibu, California.

In a career spanning nearly seven decades, Gossett became one of the most recognizable actors of his generation. With his gleaming shaved skull and the sinewy 6-foot-3 physique of a former college basketball player, he brimmed with magnetism.

In his drive to shatter boundaries as an African American performer, he worked on Broadway and other stages starting in the 1950s and appeared in dramas such as Lorraine Hansberry’s landmark “A Raisin in the Sun,” Jean Genet’s anti-colonialism play “The Blacks” and Conor Cruise O’Brien’s “Murderous Angels,” in the last as the ill-fated Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba.

He seemed poised for greater success after winning an Emmy for “Roots” in 1977 and the supporting actor Oscar for “An Officer and a Gentleman” in 1983. He was the first Black actor to receive an Academy Award since Sidney Poitier’s win in 1963 for his performance in “Lilies of the Field.” But despite Gossett’s widely acknowledged range, he found himself largely excluded from prestigious and lucrative film roles.

“I thought I’d get a lot of offers – and they didn’t come,” he told the New York Times in 1989. Several factors were at work, he later said. One was age: He was in his mid-40s, putting him at a disadvantage when competing for leading parts, especially when people of color had fewer opportunities in general. Another, he said, was the difficulty of pursuing a career while raising a young son as a divorced single father.

The pressures and disappointments became so great, he said, that he sunk into depression and became addicted to cocaine and alcohol. Gossett’s reputation plummeted after a former wife alleged during a custody battle in 1982 that their son was spoon-fed “white powder” by one of Gossett’s girlfriends. Criminal charges were dropped for lack of evidence, and Gossett retained custody, but the damage seemed insurmountable.

In a memoir, “An Actor and a Gentleman,” Gossett wrote that white actors “were able to overcome worse predicaments with drugs and alcohol and self-destructive acts.” He added: “For them, there was a hope of redemption and an even more successful career at the end of treatment, the drug problem only adding to the allure. But for a black man who was supposed to ‘mind his manners,’ the drugs were a permanent blemish. For me, the road was too narrow to have room to fool around.”

To pay the bills, he was reduced to supporting roles in low-rent action fare starring Chuck Norris and Dolph Lundgren, as well as many direct-to-video movies. And his fallen stature felt like a constant reminder of the indignities he had endured as a Black man in Hollywood, starting with his first trip to Los Angeles in 1967 to make a TV movie. He said police handcuffed him to a tree for three hours because he looked suspicious driving a luxury sports car and blasting Sam Cooke on the radio.

Even as an established name, he was told by white directors that he wasn’t acting “Black enough” or that he needed to “use those Black phrases.”

“There were times I wanted to quit altogether,” he told the Times in 1989. “Our employment was basically fulfilling Hollywood’s stereotypes about Blacks, and the whole mocking mentality of the crews – well, I wanted to leave the business.” Instead, he added, he kept “trying to find some dignity in those parts. But I carried a hot ball in my stomach for a lot of years.”

‘Roots’ and ‘Officer’

Mr. Gossett had a promising start. At 17, in 1953, he secured the lead in “Take a Giant Step,” an acclaimed Broadway drama about a troubled youth. After a torrent of strong reviews in stage parts, he moved into television, slowly transitioning from playing juvenile delinquents to less stereotyped roles as law enforcement officials and (eventually) white-collar professionals.

His professional breakthrough was “Roots,” the ABC miniseries based on Alex Haley’s best-selling book that traced the impact of slavery on a Black family across generations. The production ran eight nights and was seen by an estimated 130 million people, placing it among the highest-rated programs in television history.

“Roots” provided a rare high-profile dramatic outlet for Black actors such as LeVar Burton, John Amos, Cicely Tyson and Ben Vereen. It swept the Emmy Awards.

Mr. Gossett did not initially embrace the role of Fiddler. At first, he said, he regarded the older character as an “Uncle Tom.” But he came to see a poignant humanity in Fiddler, who lives by his own complicated code to survive in a dehumanizing system.

In perhaps his most revealing moment, Fiddler is traumatized when his young friend Kunta Kinte (played by Burton) is whipped into answering to his slave name, Toby.

“There’s gonna be another day,” he says as he cradles his friend. “You hear me? There’s gonna be another day.”

Mr. Gossett said he improvised those lines of rage and sorrow in the emotion of the moment.

Several years later, Mr. Gossett gave another evocative performance, as Sgt. Emil Foley, the D.I., or drill instructor, in “An Officer and a Gentleman” (1982). To prepare, he spent 10 days undergoing gut-busting Marine Corps drills at Camp Pendleton, Calif.

The film’s star was Richard Gere, playing a selfish loner trying to pass Navy aviation officer candidate school while enjoying a fling with a local factory worker (Debra Winger). While the movie focuses principally on Gere and Winger’s growing romantic attachment – to the ballad “Up Where We Belong” – another form of love story emerges between the D.I. and the men and women he trains over 13 grueling weeks to his uncompromising standards.

In a karate showdown and other clashes, Mr. Gossett’s Foley beats moral fiber into Gere’s callow, angry young man. (For years afterward, Mr. Gossett wrote in his memoir, he kept away from bars because his presence sometimes invited fights with drunk Whites seeking to prove that they could best him in martial arts.)

Times film critic Janet Maslin praised Mr. Gossett’s “subtlety and spark” as he navigates the layers of a man who is not entirely the abusive taskmaster he appears.

Mr. Gossett hoped that “An Officer and a Gentleman,” which grossed more than $100 million, would vault him to a higher level of stardom and pay that eluded most Black actors. Instead, he told the Television Academy Foundation, he received no film offers for a year. “People weren’t ready for me to win,” he said. “I was at the racial edge.”

He was eventually carried off in a current of derivative action films, playing a Sea World manager in “Jaws 3-D” (1983), a reptilian extraterrestrial in the science-fiction fantasy “Enemy Mine” (1985), and an ex-Vietnam War fighter pilot named Chappy Sinclair in “Iron Eagle” (1986) and sequels.

His drug habit worsened, and he started freebasing cocaine. “All my life I’d been healthy, straight, responsible,” he told the Times in 1989, noting that many members of his immediate family were alcoholics and that his father died of alcoholism-related causes. “And I’d never got high when I was working. … I had an Oscar, an Emmy, and yet I had this big hole in my soul. I was in a pit of self-pity and resentment.”

Fifteen years would pass, he said, before he overcame his addiction through rehab and newfound spiritual fulfillment. He began taking roles in many religious films, including the apocalyptic Christian thriller “Left Behind III: World at War” (2005), playing the American president.

Actor and athlete

Louis Cameron Gossett Jr., the only child of a porter and a maid, was born in Brooklyn on May 27, 1936. He described growing up in the ethnically diverse neighborhood of Coney Island with supportive White friends who gave him the self-confidence to run for senior class president at Abraham Lincoln High School (he won) and become a standout athlete in baseball and basketball.

He nurtured an interest in the performing arts from a young age, taking the subway to Harlem’s Apollo Theater to catch acts and then re-creating them for family members. With the encouragement of a teacher, he tried out for the lead in the Broadway show “Take a Giant Step,” a coming-of-age-drama by Louis Peterson about segregation in a New England town. Mr. Gossett won the part over 400 other contenders.

The show ran for only 76 performances in 1953 but drew plaudits for the unknown performer then still in high school. Theater critic Brooks Atkinson wrote in the Times that Mr. Gossett “conveys the whole range of [his character’s] “turbulence” – “manly and boyish at the same time, wild and disciplined, cruel and pitying. It is a composite of opposite impulses.”

After graduating from high school in 1954, Mr. Gossett took classes at the Actors Studio workshop in Manhattan. One day, the visiting movie star Marilyn Monroe placed her hand on his knee and breathily asked Mr. Gossett if he’d like to play a love scene together.

As he recalled to the Television Academy Foundation, he sensed immediately that this was a put-on – likely orchestrated by classmate Martin Landau, who briefly dated Monroe. “As I go out the door,” Mr. Gossett said, “Marty Landau is in stitches. He never confessed, but he set me up.”

Meanwhile, on an athletic-drama scholarship, he studied at New York University and was a standout on the university basketball team. Invited to the New York Knicks’ rookie-camp tryout after his graduation in 1959, Mr. Gossett gave up his pro-sports ambitions when he was offered a role that year in the forthcoming Broadway play “A Raisin in the Sun.”

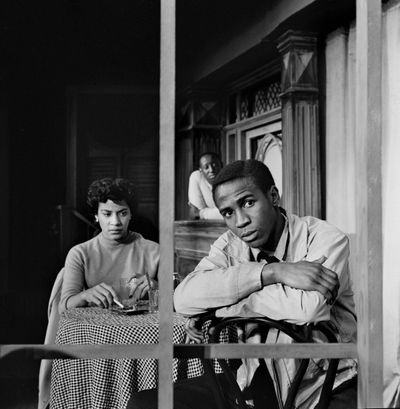

The drama, acclaimed for its sensitive portrayal of Black life, starred Poitier as an ambitious Chicago chauffeur who hopes to move his family to the White suburbs. Much of the cast, including Mr. Gossett as the wealthy college student who romances Poitier’s sister, reprised their roles in the well-received 1961 film version.

On Broadway, Mr. Gossett had a supporting part in “Golden Boy” (1964), a musical starring Sammy Davis Jr., followed by leading roles in plays such as “The Zulu and the Zayda” (1965), set in South Africa, and the Poitier-directed comedy “Carry Me Back to Morningside Heights” (1968).

Mr. Gossett also demonstrated facility as a musician. He sang and played guitar at Manhattan nightclubs and wrote with Richie Havens the antiwar anthem “Handsome Johnny,” which Havens performed at the Woodstock Festival in 1969. (“That song kept me from being homeless,” Mr. Gossett told HuffPost. “A landlord was putting me out when I got a residual check.”)

Because of an injured Achilles’ tendon, he lost the role of football star Gale Sayers to Billy Dee Williams for the phenomenally successful 1971 ABC movie “Brian’s Song.” But Mr. Gossett won arresting parts in other movies, among them Diana Sands’s ax-wielding jealous husband in “The Landlord” (1970); James Garner’s con-man partner, posing as an enslaved man in the antebellum South in “Skin Game” (1971); and a Haitian drug dealer in the sunken-treasure hit “The Deep” (1977).

He also headed the cast on the ABC medical drama “The Lazarus Syndrome” (1979), playing an idealistic chief of staff at a private hospital. Although the series got poor reviews and was quickly canceled, Mr. Gossett said he saw it as an opportunity to present a Black role model in medicine.

His marriages to Hattie Glascoe, actress Christina Mangosing and actress-singer Cyndi James-Reese ended in divorce. Survivors include a son from his second marriage, Satie; a son from his third marriage, Sharron, whom he adopted from a St. Louis homeless shelter; and several grandchildren.

In later years, Mr. Gossett led an anti-racism foundation called Eracism. He also appeared in scores of TV shows, including the HBO’s miniseries “Watchmen” and CBS’s sci-fi series “Extant.” In 2018, after his longtime home in Malibu was destroyed in a wildfire, he moved to Georgia.

Of all his roles, he said his favorite was Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in the 1983 TV miniseries “Sadat,” because he felt at the top of his craft, even as he was overlooked by most Hollywood producers.

“Each day of this filming, I felt as if I was not acting,” he noted in his memoir, written with Phyllis Karas. “Instead, I was simply in the midst of a magic that consumed me, allowing me to glide effortlessly into my role and leave everything else behind. I returned to my own reality only after the cameras were turned off. Sometimes I believe that the reason I have been able to do such exemplary work on the screen is because this is the only place I can be free, neither censured nor judged.”