Summer Stories 2025: ‘Next of Kin’

Sheriff hands me the fax, watches over the top of his glasses as I read. Bad news from a neighboring county. He says, “You’re gonna need to go see the widower.”

“But–” I say.

“Not what I want, either. But this wind.”

I can hear it out there: a thin, shrieking howl. A power line’s down on Five Mile, sparking in the road. An empty cattle trough tumbled end over end onto the highway and into an oncoming pickup. The big evergreen in front of the Presbyterian church blew down, limbs crashing through a stained-glass lancet window.

“My hands,” Sheriff says, turning his palms to the sky, “are full.”

He gives me a Stage 4 cancer kind of look: I’m sorry you’ve got it, but you do.

We leave together, he to his cruiser and me to my pickup. Pellets of dust sting my face. A sidewalk sign cartwheels past: Mode O’Day Finest Ladies Fashions. Cars creep by on Main, headlights jaundiced in the midday dark.

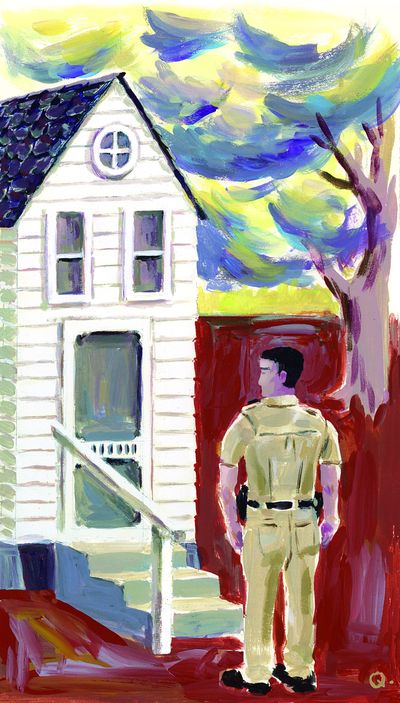

I am a special-purpose reserve deputy in the Gooding County Sheriff’s Department, hired two months after my high school graduation to hand out trays in the jail, guide traffic at the rodeo and serve the occasional subpoena. Sheriff hired me because he and his deputy were stretched thin by the investigative demands of Gooding’s first murder in five years – our small-town crime wave. He knew me from Explorer Scouts, and liked me, I guess, or thought I had an aptitude. I wasn’t sure yet what I had an aptitude for. If anything. Sheriff said I could gain experience leading to a lifelong career in law enforcement; he gave me a silver badge and a brown uniform shirt with golden patches, which I wore with Levis. At home, in my apartment, I would put it on and look at myself in the mirror. I felt like I was dressed for a Halloween party.

I drive north, fizzing with dread, fax folded in my front pocket, fighting the wheel as gusts push the truck around. The last thing Sheriff said was, “Relate the facts, say you’re sorry for his loss, tell him to call this number.” He had written the number of a funeral home in Jerome on the fax. “Don’t think about it too much. There ain’t any good way to do it.”

A mile out, I come to the farmhouse, shrouded by two tall oaks waving their arms in the wild brown air and a flailing wall of lilac bushes, stripped clean. The house seems quiet. Windows dark.

The wind here is grittier, thicker. I feel it in my eyes and lungs. I go to the back door, and pull open the screen, which the wind rips from my hand and slams against the wall. I knock, wait, knock. A full minute passes, as a sense of warm relief loosens me all over. The world has recognized that I am not right for this task, and it has arranged this empty house in recognition of that fact, and I want to drop to my knees and thank the world for that.

I turn and look out at the dirt yard between the house and shed, which groans and creaks in the wind. A burst of dust scoots across the ground.

I feel so good. Like the wind carried off my dread. I decide I will knock once more, knock loudly so I can say I tried my best, then leave.

I turn to find an old man standing with his door open, squinting.

“Mr. Boyer?” I say, words blown from my mouth. “MR. BOYER?”

He shakes his head and points to his ear. He steps aside and waves me in. In the entryway, he asks, in a phlegmy baritone, “Is something wrong?”

On the drive out, I rehearsed what I would say. Practiced it, stating the bare facts: Gray Corolla. Eastbound on I-84. Crossed the median into. Dead at the.

Even just pretending, my voice trembled.

What I hadn’t practiced, though, was how I would begin. How I would make my way to those words I practiced.

Is something wrong?

“Oh no,” I say quickly, as if the words were blown through me. “There’s nothing wrong.”

He looks at me, waiting. He wears a flannel shirt buttoned to the neck and wrists, and suspenders. He is big, thick in the chest, and his face shows the years of farm life: weather-rough, tanned, spots of raw skin high on his cheeks, criss-crossed by a map of tiny veins.

“Well?” he asks.

“I just needed to talk to you,” I say. “For a minute.”

“Somebody like you shows up at the door,” he said. “Not good news.”

“No, no,” I say – and again, like it’s not even me: “Everything’s fine.”

I follow him to the living room. He limps in, side to side, suspenders crossed on his back, and lowers himself into a recliner. I sit on the couch. On an end table beside the chair stands a little skyline: orange pill bottles, a telephone, a folded newspaper, and a reading lamp.

“So?” he says.

I think and I think.

“Everything’s fine, but you just needed to talk to me for a minute,” he says.

I think and I think and I think but my mind is a gear that will not engage. I am 18 years old, sir, is all that comes to me.

“There was some reason you came here, right?” he says.

Behind him, in the big picture window, the world is brown and loud and strange.

I know these people. The Boyers. Somewhat. And they know me. They went to my grandmother’s Methodist church, and Mrs. Boyer was my Cub Scout leader when I was in second grade and I was friends with her grandson, Bucky Boyer, who lived with them for a time back then, before returning to his regular family somewhere else. We had been good friends that year, Bucky and I, but I have no idea what has become of him, and sitting here I can’t picture his face, and I can’t picture Mrs. Boyer, either, but I remember coming out here, to this house, and doing some kind of craft thing for Cub Scouts – putting beads on a leather thong – and I remembered her serving us little mayonnaise sandwiches on soft white bread, crusts trimmed off, cut into triangles.

“We’re just out checking on people,” I say at last. “Seeing if there’s any damage or problems.”

“Any problems,” he says.

“With the wind,” I say.

He wears a look that I recognize – the way Sheriff looks at someone who is telling him something he doesn’t believe.

“You’re just out checking to see whether I’m having any problems with the wind?” he says.

“Yes,” I say. “Trees down. Any damage or anything.”

“But everything’s fine?” he says.

“Yes.”

I can barely hear myself. I stare at the shelf of figurines behind him. Little ceramic children. German or something. A chubby-cheeked boy peering out from under an umbrella. Two kids climbing over a wooden fence.

“Son?” Mr. Boyer says.

“Yes?”

“You need to tell me why you’re here.”

“I know,” I whisper.

In the window, a tree limb tumbles awkwardly past, bone white where it split free. I feel like a piece of wood myself, stiff and mute and sad and dumb. A puppet that has not yet been turned into a boy.

Mr. Boyer exhales loudly. Gets up, lumbers toward me. I think he might coming to give me a beating, but he sits beside me.

Little mayonnaise sandwiches. Soft little triangles. Crusts trimmed off. Like nothing I’d ever seen before. Neat and soft and exotic and delicious. I could almost taste them.

He puts a heavy hand on my shoulder.

“I know I do,” I say again.

“This is about May, right?”

I nod.

“Something happened to May.”

“Yes,” I say.

I take the fax from my pocket and unfold it and hand it to him.

“I’m sorry,” I say.

He nods. He squeezes my shoulder, as if he’s comforting me. He says, “Told her not to go out in this,” and a sound comes out of him, like he’s being squeezed by a giant hand.

He says, “Ah, May. My word.”

And then: “Thank you for telling me.”

The wind blows deep into the night and when it stops, the silence wakes me. I look at the ceiling, pebbled in the moonlight through the window. I sit up. My uniform shirt hangs on the back of a chair, the badge invisible in the dark. There is a sound inside the silence, as if everything that was stirred up is sifting down like snow. I see into the future – or maybe it’s not the future, maybe it’s only a wish: I place the shirt and badge in a paper bag and carry it down to the station and hand it to Sheriff and tell him I’m sorry but. I drive to Safeway, where I hear they need a night clerk, and I’m hired and given a different uniform – a brown vest and a brown tie freckled with little orange S’s – and every night after the store is closed and half the lights are off, I fill the shelves neatly with pancake mix and vegetable oil and Count Chocula and tomato soup. I go home at first light and sleep through the mornings and wake up in the afternoons, ready to make a friend of the night.