Then and Now: First Waterworks

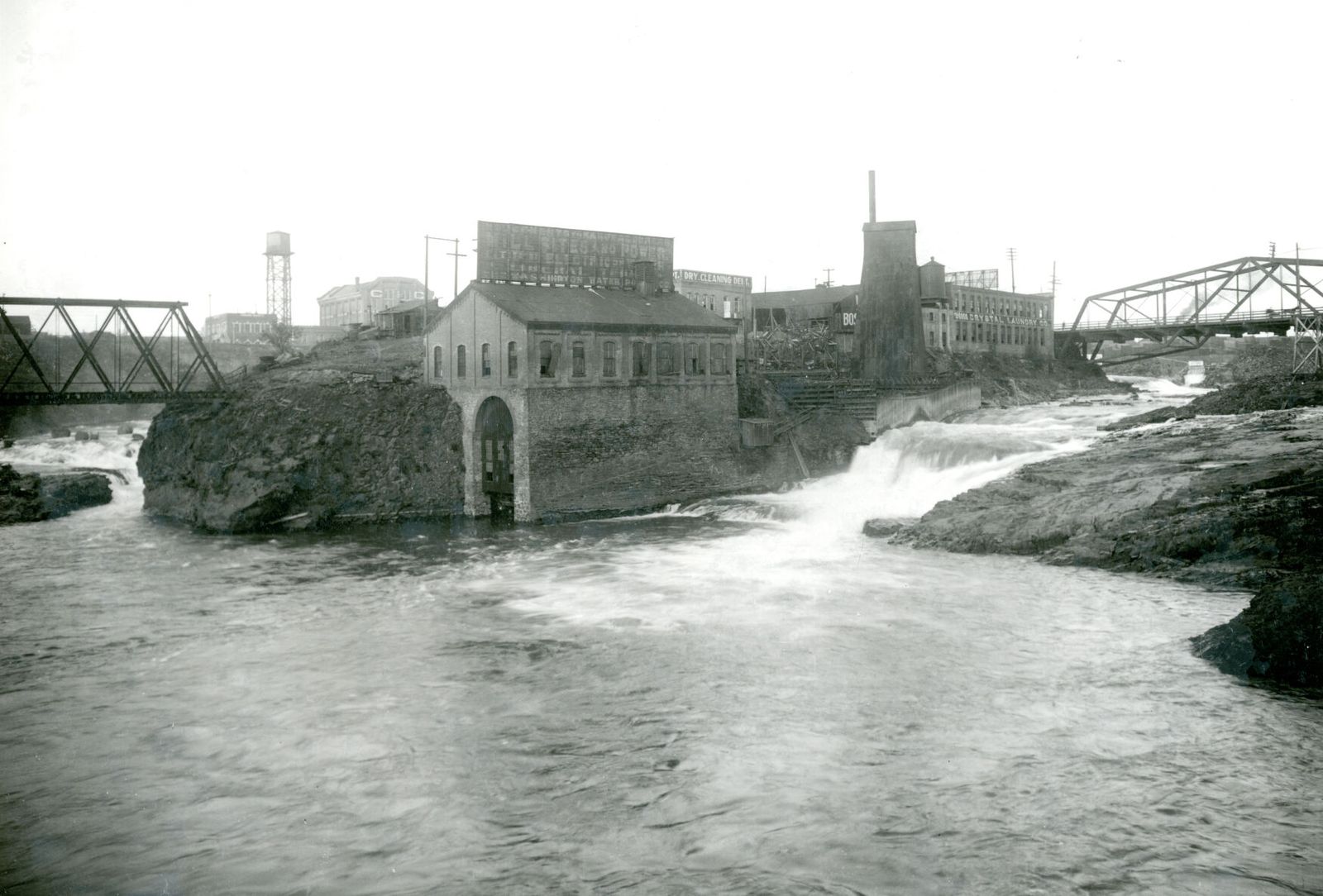

The first waterworks plant, on what was then called Crystal Island, was completed in 1888, was built to pump running water into Spokane for the first time, and provide fire protection. Or so they thought. Traces of the foundation can still be seen on the rocky bank of Snxw meneɁ (sin-HOO-men-huh), the name given the island in 2017 to reflect the history of Native people in this area.

Section:Then & Now

Then and Now: First Waterworks

Traces of the foundation of Spokane’s first waterworks still cling to the side of Snxw meneɁ (sin-HOO-men-huh), once called Crystal Island, and later Canada Island, in the middle of the Spokane River. The small island was given a Salish name meaning “salmon people” in 2017 to reflect the Native peoples who camped and fished by the river centuries before white settlers arrived.

In 1884, when many residents still carried river water to their homes for cooking and bathing, city officials hired Rolla A. Jones to build a water plant.

Jones was a businessman who ran a jewelry store in Spokane and had other interests around the region.

The progress toward running water in Spokane paralleled the effort to develop hydropower electricity in the city, which started with small generators placed on or near the river.

The new waterworks incorporated a Holly Fire Protection System, the latest technology for firefighting, which integrated a steam engine, rotary pumps and patented hydrants. Before the new system, volunteer firefighters brought water to fires in tank wagons, a slow and laborious process.

Jones had installed the system, but he was in Coeur d’Alene, working on a steamboat he owned, on Aug. 4, 1889, the day Spokane’s great fire broke out.

Another man fired up the water system, but for some reason could not activate full power. People watched helplessly as the fire devoured more than 30 square blocks of downtown buildings.

People would later blame Jones for the extent of the damage because he was unavailable. Some would say he was pleasure boating or fishing while the city burned.

Jones resigned as water superintendent.

City and county officials knew that river water downtown would never be reliably potable because of sewage that went into the water upstream. The city decided to switch to wells and build a new water plant near what is now Felts Field.

Jones was hired to build Upriver Dam by the new water plant. The wooden dam was finished in 1896 and generated the electricity for the pumps that moved the water. The old waterworks building was abandoned. Washington Water Power Co. eventually acquired the building, which was mostly gone by the 1920s, according to one newspaper story.

Jones died in 1934 at the age of 71.

The remainder of the foundation was removed just before Expo ’74.