Washington wolf shot in Montana after roaming 700 miles

A young male wolf captured and GPS collared by state wildlife biologists in northeastern Washington left the Huckleberry Pack in June 2016 and roamed about 700 miles in three months before being shot by Wildlife Services as it attacked sheep in Central Montana. (Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks)

UPDATED 5:15 p.m. with quotes from Scott Becker, Washington Fish and Wildlife Department wolf capture and monitoring leader who was involved with collaring the far-roaming wolf.

ENDANGERED SPECIES — A young gray wolf that left its pack in northeastern Washington this summer traveled about 700 miles before being shot in central Montana last month while attacking sheep.

The 2-year-old male wolf was captured in February by Washington Fish and Wildlife Department biologists and fitted with a GPS satellite tracking collar. It began wandering northeast into the Idaho Panhandle in June, headed into the Moyie area of British Columbia before crossing Lake Koocanusa and trekking southeast into Montana near Eureka on July 4.

“We have no clue how the wolf crossed the reservoir,” said Scott Becker, Washington Fish and Wildlife wolf capture and monitoring leader who was involved with collaring the footloose wolf. “It could have swam or used a bridge; it probably didn’t hitchhike.”

A federal Wildlife Services agent near Judith Gap, Montana, shot the wolf on Sept. 29 as it was killing sheep near Judith Gap, Montana.

The wolf originated in the Huckleberry Pack, which roams from the Spokane Indian Reservation north into Stevens County.

“Dispersal is a necessary and a very risky component of wolf population dynamics,” said Ty Smucker , Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks wolf specialist.

“By late July it was on the Rocky Mountain Front and Washington Fish and Wildlife called to let me know,” Smucker said. The wolf’s locations were monitored weekly by Washington biologists and related to Smucker in Montana.

Wolves in Eastern Washington are protected by state endangered species rules. However, wolves have been removed from federal and state protections in Montana and Idaho and opened to hunting and trapping.

“The wolf came out on the Rocky Mountain Front just east of Bean Lake on July 22,” Smucker said. “Then it spent over a month and a half moving around the lower Dearborn River Country, before heading toward Square Butte west of Great Falls on Sept. 13.”

From Square Butte, a prominent land feature near Geraldine, Montana, the wolf turned east and emerged on the foothills of the Little Belts west of Judith Gap on Sept. 22, Smucker said.

Responding to a report of a wolf killing sheep, Wildlife Services killed the collared wolf Sept. 29. Montana officials said the wolf had been chasing and feeding on a band of sheep. Montana does not capture and relocate problem wolves, Smucker said.

“It had to travel at least 700 miles total,” he said. The young wolf would ultimately be looking for a mate, but no wolf packs currently occupy that portion of Montana, he said.

“It’s not surprising when a wolf disperses,” said Becker. “A lot more wolves that aren’t wearing collars go all over the place looking for social openings and new territories. It’s what a wolf does.”

“Wolf packs consist of breeding pairs that generally produce four-to-six pups each spring,” Smucker said. “As young wolves mature they typically disperse from their natal pack in search of potential mates and vacant territories in which to start their own packs.”

Sometimes that search can take the animal on a long journey. In 2015, a wolf wearing a GPS collar left its pack’s territory west of Missoula and ended up 600 miles north in British Columbia.

OR-7, a wolf collared in Oregon in 2011, became internationally famous for its 1,000-mile loop into California and back to Oregon before it found a mate in 2015 and started the Rogue River Pack.

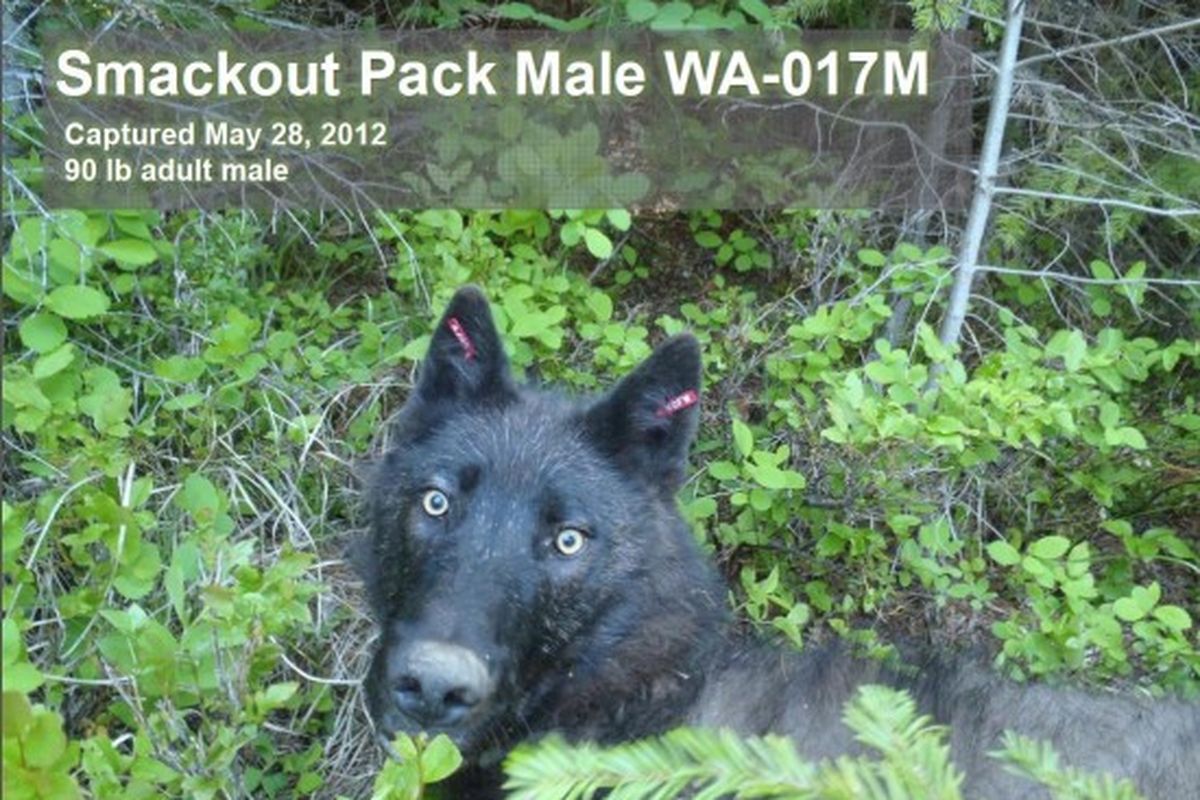

Similarly, Washington male wolf caught and collared in 2012 from the Smackout Pack of Pend Oreille County was tracked on a romp of more than 500 miles to an area 300 miles northwest of Oroville .

That wolf caused a rustle among DNA researchers who had previously assumed a population of coastal gray wolves in British Columbia was distinct.

The long-distance travels of wolves documented by GPS technology also prompt doubts about theories that the 1995 release of Canadian wolves into Yellowstone introduced a subspecies that was larger and different than the wolves that had been extirpated from Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and Wyoming.

There’s never been a wolf-proof fence along the international boundary, researchers point out.

While noting research that indicates distinct sub-species of wolves in North America and even the Northwest, Becker says GPS tracking has proved that “wolves have always been capable of traveling long distances and hooking up.

“What this wolf did is the primary reason we have wolves in Washington,” he said. “We didn’t reintroduce them here; they moved in on their own (from Canada and Idaho).”

Becker said dispersing wolves make up 10- 20 percent of a region’s wolf population on an annual basis.

Montana’s wolf population has stabilized for the past eight years at a minimum of more than 500, Smucker said. At the end of 2015, Idaho reported a population of about 800 wolves and Washington had a still-growing population of more than 90 wolves.

* This story was originally published as a post from the blog "Outdoors Blog." Read all stories from this blog