This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: Cutting funds for state auditor’s office is punitive, counterproductive

The office took a look at eight county jails – including Spokane County’s – and found that, at just those jails, $655,736 in jobless benefits had been paid to inmates in a 15-month period, spread out over more than 1,900 improper payments. The audit concluded that the state Employment Security Department didn’t have access to jail records – something that had recently been granted to several other state agencies that oversee various benefits payments – and suggested that the Legislature correct this oversight.

These days, there is a lot of talk of accountability and reform among lawmakers, and especially among the GOP, which has seized control of the Senate and been feeling its oats as the watchdog of Gov. Jay Inslee’s appointees.

But the passion for accountability did not extend to the budget.

The Legislature – both the Democratic House and the Senate – cut funding for performance audits by $10 million in the recent supplemental budget, on top of $12.6 million in the biennial budget passed last year. That’s 74 percent of the budget for performance audits – and a terrible decision by everyone involved.

It’s possible that Inslee may exercise the line-item veto and fix this. Barring that, however, the state will spend less time and energy and, yes, money on the best tool we have for double-checking the work of government. Hot talk and political beheadings are accountability theater; the auditor’s office does the real work.

Consider some of the areas of government the office examined in just the past year: improving staff safety in state prisons; evaluating long-term outcomes for students enrolled in alternative learning programs; identifying overlap and duplication among the 55 state agencies that have a hand in workforce development; filling the holes in the state’s criminal history database; and considering a program to help the state collect delinquent debts, among many others.

The story of the auditor’s budget and the Statehouse is somewhat complicated, but at the root is a very simple situation: the indictment of Auditor Troy Kelley and Kelley’s subsequent refusal to resign. Kelley faces a 10-count federal indictment for theft, connected to allegations that he illegally kept millions of dollars in fees that he should have returned to clients of the real estate reconveyance firm he owned before he was elected auditor. He should have quit long ago, but the fact that he hasn’t doesn’t cast light on the auditor’s office as much as it does him personally.

Sen. Michael Baumgartner, a Spokane Republican, said that the “biggest reason not to fund the auditor’s office is because of Troy Kelley.” But he also said that he didn’t think Kelley’s case should reflect on the auditor’s office or its important work, and he said he and some of his fellow Republicans think the office should have been better funded. He noted that the governor’s initial budget included the $10 million cut, and that Senate budgeters tried to restore a little of that money.

“I think our guys think we probably should have put more money into the auditor’s office than the governor did,” he said.

Jan Jutte – who has postponed her retirement to run the auditor’s office during Kelley’s leave of absence – described the process a little differently. The initial cuts were built upon an oversight by the governor’s budget writers, who miscalculated the fund balance left over from the last biennium, she said. Initial proposals included plans to “sweep” this leftover money into the general fund; by the time lawmakers were through, however, the $10 million had been actively removed from the auditor’s budget and distributed to another agency.

Jutte said some lawmakers were explicit that the cut was tied to Kelley’s indictment.

“We had a few legislators who told us we were in a weak position because of Troy Kelley,” she said.

I asked her: Wouldn’t the Kelley scandal naturally give someone legitimate reason to doubt the office?

“That is totally wrong,” she said. “I’ve worked in this office for 31 years. This office is operating with the same integrity and transparency that we always have.”

She added, “What Troy Kelley did, he did before he came to this office. … It has nothing to do with this office.”

The budget cut seems especially ill-advised. Eleven years ago, Washington voters passed Initiative 900, establishing an excellent method of auditing government, providing sales-tax money to finance it, and requiring legislative hearings on audit findings. I-900 was a Tim Eyman initiative, and it was a winner. Unlike many of his proposals, it worked toward improving – rather than simply slashing – government.

Since I-900 passed, lawmakers have frequently raided that sales-tax funding for other purposes. But this year’s cuts are something new. Jutte has already canceled contracts for outside auditors – whom the office retains in cases where specialized expertise is needed, such as cybersecurity. She’s not yet sure which in-house audits will be canceled or scaled back, because her efforts have so far been focused on determining how many people she’ll have to lay off. So far, six people have left voluntarily, and another 10 will have to be laid off from a staff of 53.

Unless, that is, Inslee gets out his veto pen.

“Taking money from us just seems so counterproductive,” Jutte said. “We can be part of the solution. We’re not part of the problem.”

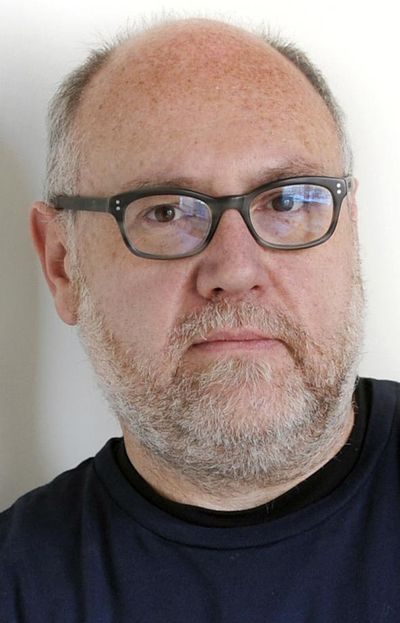

Shawn Vestal can be reached at (509) 459-5431 or shawnv@spokesman.com. Follow him on Twitter at @vestal13.