This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: Burgess, GU’s original All-American, also stood at the center of a fair housing case in Spokane

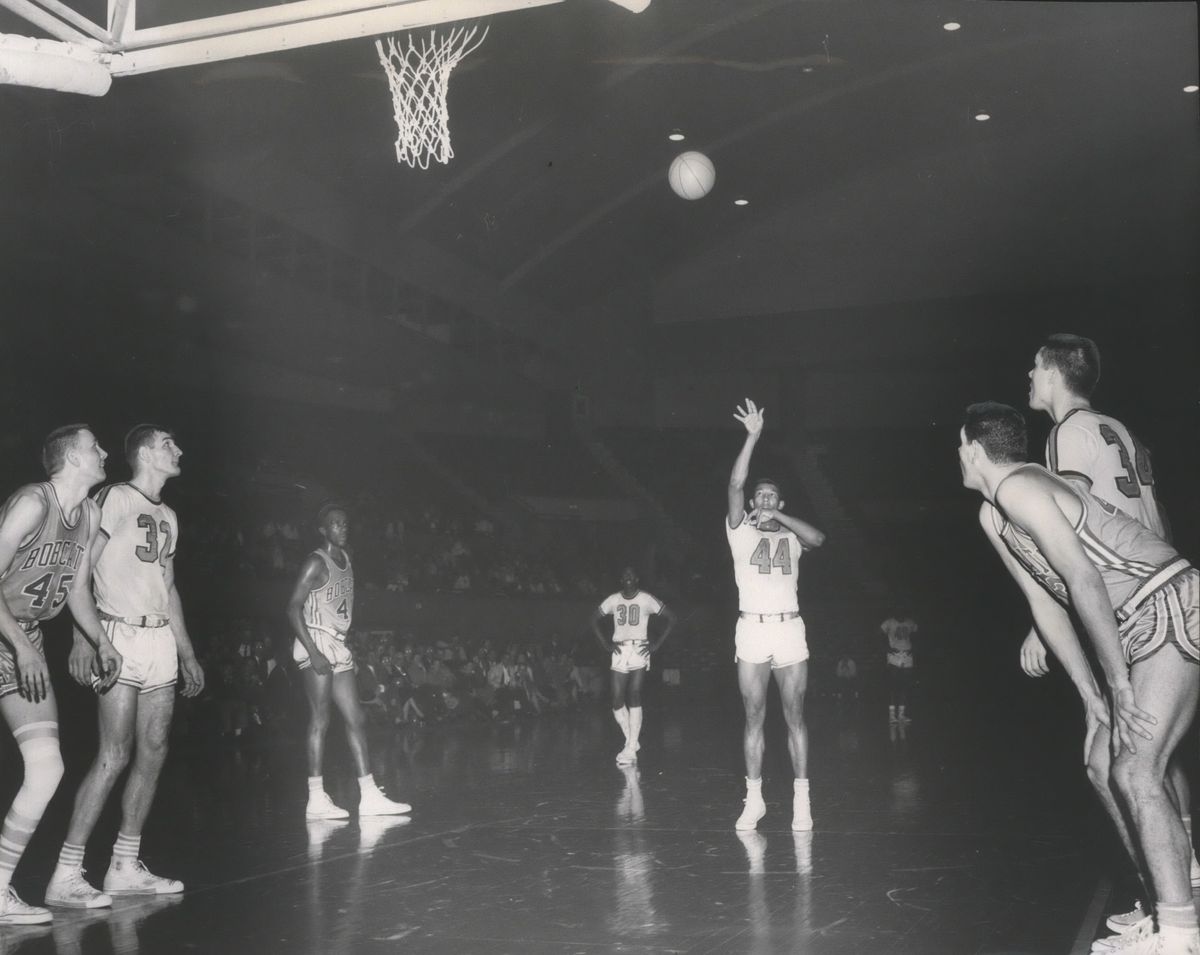

Gonzaga’s Frank Burgess tosses the free throw that produced the winning point in an 80-79 hoop conquest of Montana State last night at the Coliseum. The shot came with just six seconds left. (The Spokesman-Review photo archive)Buy a print of this photo

As the clock runs out on Frank Burgess’ scoring record at Gonzaga, it’s a good time to revisit a short but revealing chapter from his life in Spokane in the 1960s.

Burgess was Gonzaga’s first All-American, led the nation in scoring and went on to play briefly as a professional in the short-lived American Basketball League before returning to GU Law and moving on to a distinguished legal career that ended on the federal bench. His prowess on the court and his legal legacy have been well-documented in recent columns by Dave Boling; Burgess scored 2,196 points in three seasons, a figure that Drew Timme is within 21 points of surpassing.

In the years immediately after he stopped playing basketball, Burgess, who grew up as the son of a sharecropper in Arkansas, also was involved in a case of apparent housing discrimination in Spokane – a case the pioneering civil rights attorney Carl Maxey took to court and won in 1965.

The matter centered around an $80 deposit Burgess had paid to lease a home in Northwest Spokane. He was later denied the chance to move into the home, and the property owner’s agent told him the “neighborhood reaction had created pressures” to cancel the contract, Burgess said in a sworn statement in the case.

“GU Cager Great Files Court Suit,” read a small headline on page 16 of The Spokesman-Review in July 1964.

That short item outlined the case: Burgess was suing a property owner and his agent “claiming he obtained an option to lease a house in Spokane but was not allowed to exercise it.”

The article also noted, “Burgess is a Negro, but the complaint does not mention race as a factor.”

It is true that the suit did not advance a legal argument of discrimination. But Maxey, who had become “the region’s point man in the struggle for fair housing,” believed it was a matter of racial discrimination, according to the book “Carl Maxey: A Fighting Life” by former Spokesman-Review reporter Jim Kershner.

“Maxey told the judge, Ralph E. Foley … that the refusal was clearly because of race,” Kershner wrote. “Yet Maxey’s main legal argument wasn’t about race; he simply argued that the $80 payment constituted a binding contract.”

There was little in the way of legal recourse for housing discrimination at the time. While there had been important Supreme Court rulings against housing discrimination – 1948’s Shelley v. Kraemer ruling banned racially restrictive housing covenants, for example – discrimination against African Americans and other people of color remained common.

Stronger federal anti-discrimination law, through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, was on the way but hadn’t arrived yet.

Burgess sought to lease the home at 3009 W. Eloika Ave. for himself, his wife, Lillian, and their two children in the spring of 1964 after seeing an ad in the local paper. Burgess was a GU law student at this point and vice president of his class.

He paid $80 – a month’s rent that secured an option for a one-year lease – to the homeowner’s agent, R.A. Griepp. The home was owned by Ray Ruth, who was living in Billings..

Two days after Burgess gave Griepp the check, the agent called back to indicate there was a problem, according to Burgess’s statement – saying “for one thing, the owner would prefer to sell than lease” the house.

“I said, ‘What is the other thing?’” Burgess said. “Conversation with Griepp indicated that neighborhood reaction had created pressures necessitating Griepp’s call for the purpose of attempting to repudiate the contract.”

Griepp returned Burgess’ check by mail. In sworn statements, Ruth said he had simply decided to trade the home for a house in Billings, where he was living. He said it had always been his preference to sell the house, not lease it.

“I would like to say I have no discriminatory feelings toward the Negro race, and never have, but houses are not easy to sell and especially when living so far from the property,” he said.

The case went to trial. In the meantime, a local group advocating for racial justice – Citizens for Reconciliation – took out an ad in the Spokane Daily Chronicle in June 1965 saying that the case “proves that racial discrimination in housing does exist in Spokane and that it should be recognized and protested.”

That ad – like Maxey’s work – reflects the reality that the civil rights movement was active, if not huge, in Spokane during the 1960s. Just a year before Burgess made his down payment, the “Haircut Uproar,” as the newspapers called it, had led to a court case and public demonstrations decrying racism and discrimination.

In that case, a GU exchange student from Liberia, Jangaba “Gus” Johnson, had been refused service by a local barber. Maxey took the matter to court and won; the barbershop was picketed by groups of GU students, even as some in Spokane’s establishment rose to the barber’s defense. The barber’s attorney argued in court that forcing him to cut a Black man’s hair was akin to slavery itself.

That was part of the context in which Burgess’ effort to find housing played out. Judge Foley ruled in his favor, finding that the $80 payment established a binding contract, and ordered the payment of $250 in damages.

In his order, Foley outlined how racial discrimination affected Burgess after he was denied the home on Eloika, making it difficult to find another place to live. Burgess made five calls to rental homes over three months, without success. The house he eventually did rent was “not as good” as the one he was “deprived of,” Foley said – noting that it lacked paved streets and curbs, a driveway, a finished basement, and a garage, and cost almost as much.

He won the case, in other words. But it was a qualified victory, at best, for GU’s original All-American.