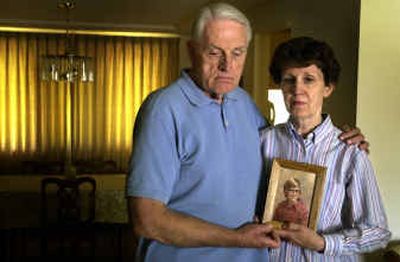

Couple seeks reform after son’s suicide

The church was their world.

As devout Roman Catholics, Terry and Ann Corrigan looked to the church for spiritual guidance, meaning and moral clarity. They devoted their lives to Assumption of the Blessed Virgin, their parish home for more than four decades.

But when their son died two years ago, their world – and their faith – nearly shattered.

Tim Corrigan was 39 and the father of three young children when he ended his life on an August afternoon, several hours after seeing a newspaper photograph of a priest now accused of molesting dozens of boys.

Ann and Terry Corrigan never really knew how much suffering their sons, Tim and Mike, allegedly endured at the hands of Patrick O’Donnell, a man they trusted.

They only found out after Tim killed himself.

The secret buried deep inside by his brother, their friends at Assumption Parish and many other men who were allegedly abused as children came into light when word spread about Tim’s suicide.

Since then, 18 lawsuits representing more than 50 victims, including Mike and Tim, have been filed against the Diocese of Spokane, alleging that church officials didn’t do enough to protect children from sexual predators. Half of those victims identified O’Donnell as their perpetrator.

As they slowly emerge from the shock and heartache, Ann and Terry Corrigan – who are still committed Catholics – want to make sure what happened to their sons will never happen again. Although they’re not part of the lawsuits, the couple wants to hold Bishop William Skylstad and the diocese accountable for allegedly allowing pedophiles like O’Donnell to continue preying on children. It’s not enough for church officials to simply be sorry for what happened, said Terry Corrigan; they must also apologize to victims “for covering up the abuse.”

“The crisis in the church is not the scandal,” he said. “It’s the hierarchy’s abuse of power. It’s the cover-up.”

On Aug. 29, the anniversary of their son’s death, the Corrigans will be joined by friends, family and many others during a vigil to honor Tim’s memory and to take a stand on behalf of other victims of childhood sexual abuse.

Despite the torment their son must have endured, despite the tragedy that has befallen their family, despite that sense of betrayal, Ann and Terry Corrigan remain dedicated to the Catholic Church. Every Sunday, they attend Mass and receive communion. Although they briefly went to church at St. Aloysius shortly after Tim’s death, they returned to Assumption Parish before the year’s end.

Ann and Terry, both in their 60s now, were raised in the Catholic Church – “It’s in our bones, it’s so much a part of us,” Ann explained. In 1962, when their oldest child Mike was 2 months old, the couple bought a house in northwest Spokane, specifically so they could attend Mass at Assumption and so their children could walk to the parish school. Over the years, the Corrigans served in various church boards and volunteer positions, including the parish council, as Eucharistic ministers and lectors, as the people distributing milk to kids during lunch. Terry Corrigan spent years leading the Serra Club, a Catholic organization that supports the bishop and priests and fosters vocations among those considering religious life. Every year, they not only sent birthday cards to the priests of the diocese, they also remembered the anniversaries of their ordinations.

When their son committed suicide, only six priests expressed their condolences. The Corrigans were in too much grief to care, but looking back, the lack of sympathy from the church was disappointing. Although the bishop tried to contact them days after Tim’s death, he hasn’t been in touch at all, according to the Corrigans.

“My faith does not lie in bishops, priests or buildings, but on the word of Christ,” said Terry Corrigan. Some abuse victims and their families have left the church or have become fed up with religion in general, but the Corrigans chose “to hang in there to help return the Catholic Church to the people.”

The bishop and the Rev. Steve Dublinski, vicar general of the diocese, were both out of town and unavailable for comment. In previous interviews, however, Skylstad has pledged to seek input from the laity, reach out to victims of clergy sex abuse and ensure children’s safety. “We’re not into covering up and protecting the church,” Skylstad said. “We want to support victims in their healing and reconciliation.”

Deacon Eric Meisfjord, director of communications, said Thursday: “As a concerned pastor, the bishop’s heart and prayers go out to any parent who loses a child, under any circumstances.”

A year ago, Ann and Terry Corrigan were too fragile to talk about their son, they said. But since then, they’ve found a path toward healing, thanks to the support of other victims of clergy sexual abuse. In the past year, members of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests reached out to them to offer support. The Corrigans’ spirit also has been bolstered by the encouragement they’ve received from Voice of the Faithful, a group of lay Catholics seeking accountability from church leaders and pursuing reform.

Many victims of priest abuse in Spokane have told them it was Tim’s death that spurred them to break the silence surrounding their own experiences with abuse. Although it was likely not his intention, he became their martyr.

Steve Barber, another O’Donnell victim, said he fell into a panic attack when he read the same article and saw the same photo that triggered Tim’s suicide. He never met Tim, but when he learned about his suicide days later, Barber decided to go public with what happened to him in order to fight for justice, he said. “I couldn’t fathom more people taking their lives,” said Barber. Tim’s death “forever changed my life.”

As Terry and Ann Corrigan listened to the painful stories of abuse, they, too, found the courage to speak. “Hearing their stories has given us strength,” said Ann Corrigan.

Tim Corrigan wasn’t the first O’Donnell victim believed to have committed suicide as a result of the abuse. According to SNAP members, they know of two other men who ended their lives because they could no longer live with the shame and torture of the abuse inflicted on them as boys. On the day Tim Corrigan took his own life, the newspaper story with O’Donnell’s photo contained information about a Garfield couple whose 12-year-old son was molested by O’Donnell in the late ‘70s. Their son committed suicide in 1990 and referred to the alleged abuse in his suicide note.

Tim also was 12 years old when he was allegedly abused by O’Donnell. A sandy-haired boy with a toothy smile and thick-rimmed glasses, Tim was a gentle spirit, his mother said. He was kind, even-tempered and the voice of reason among the four Corrigan siblings. Although he made a living as a computer technician, his real passion was the outdoors. He spent weekends hiking, fishing and reveling in nature. “He liked nothing more than being in the beauty of God’s creation,” a friend said during the funeral at Garland Alliance Church, where Tim and his wife, Cheryl, attended services with their children. Friends spoke of his patience and dependability, his talent for building campfires and barbecuing salmon, the hilarious stories he told during the annual “spring fling” or “primal release weekend,” which he spent every year with his brother and several childhood friends.

Above all, friends and family said, Tim loved his three children, whom he tucked into bed every night after reading them a story.

“If Tim were your son, brother or friend, he was the best you could ever have,” said Terry Corrigan.

In many ways, the Corrigans feel betrayed. They trusted O’Donnell, who was the associate pastor at Assumption Parish when their sons were molested. They believed in Skylstad, who was Assumption’s head pastor at the time and lived in the same rectory as O’Donnell when he was allegedly committing countless acts of abuse. Both men were family friends, as far as the Corrigans were concerned. They were priests, holy men revered by the Catholic community.

“O’Donnell groomed us, as well,” said Ann Corrigan. “He was so charismatic and charming. He knew which families were vulnerable.”

“We were duped,” said her husband, his voice filled with disbelief. “Catholics, in general, were duped. I can’t believe we were so gullible.”

In a previous interview, Skylstad said that when he was the pastor at Assumption, he was not aware of abuse committed by O’Donnell. “There is an assumption that the bishop knew everything,” he said. “But even in very intimate family circumstances, people are not aware of what’s going on.”

While some have commiserated with the Corrigans’ loss, many Catholics haven’t expressed any outrage over the church’s sex abuse crisis, which has affected countless victims and their families, the Corrigans said.

Their silence – their willingness to continue to “pay, pray and obey,” in Terry Corrigan’s words – has saddened the couple. They often ask themselves if this hadn’t happened to their own family, would they have questioned the hierarchy? Would they be as outraged? “Would we be pew potatoes as well?” asked Terry Corrigan. “I would hope we would’ve spoken out.”

As they forge ahead on the path toward healing, the Corrigans continue to find solace in prayer. They pray for their family, asking God for the grace and strength they need to deal with the tragedy in their lives. They pray for the bishop, “that he will have a change of heart,” said Terry Corrigan. They pray for the victims, that they find comfort and peace, and that there will be no more suicides.

And most of all, they pray for children, that they will be safe from abuse and protected from the harm that led to the loss of their own son.