Private screeners look to rebound

After suffering sharp ridicule from the public and near extermination by the federal government more than two years ago, the airline screening industry is seeking a comeback at U.S. airports.

The federal law passed after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks that banned private companies from airports allows them to return by 2005 if they are approved by the government. The provision has led a few security firms – many of them new to the business – to begin pitching themselves to undecided airports as a class above the old guard of airport screening companies such as Argenbright Security Inc., which took the brunt of criticism after Sept. 11.

“The business prior to 9-11 didn’t have the best reputation,” said Nancy Montgomery, vice president of strategic accounts at Barton Protective Services Inc., a company that employs security guards at office buildings and would like to get into the airport security business. “It’s a very different program now.”

Three companies have an advantage in the new industry because they are already operating security checkpoints at the San Francisco, Kansas City, Mo., Rochester, N.Y., and Tupelo, Miss., airports, which are participating in a $127 million pilot project. One company, FirstLine Transportation Security Inc., worked in airline security before 2001 and has changed its name. Another, McNeil Technologies Inc., is a minority-owned firm that, like many new contenders, has traditionally provided security services for government agencies.

Some new entrants already work in related businesses. Gate Safe Inc., an Atlanta company seeking checkpoint security contracts, screens airline food and other supplies before they are loaded onto planes. “It’s a natural extension of the way that we’ve grown our business,” said Larry P. White, director of marketing and sales at Gate Safe.

Airports also can get into the business by forming a subsidiary company to perform security screening, as the Jackson Hole Airport Authority has been doing through a test program with the government at its Wyoming airport.

Excluded from the business are many of the companies, including Huntleigh USA Corp., Wackenhut Corp. and Argenbright – now known as Cognisa Security Inc. – that employed a majority of the screeners three years ago. Those companies are units of larger firms based overseas and are now prohibited under federal law from working at security checkpoints. “The overwhelming majority of Huntleigh’s business has been wiped out,” said company spokesman Robert H. Bork Jr. “What little they have is not profitable.”

At least one firm, Wackenhut, is lobbying to be let back in to airport screening.

Department of Homeland Security officials estimate that up to 25 percent of the nation’s 429 airports may eventually sign on with the private security firms. For now, airports say they are interested in the option but are hesitant to decide until the government clarifies how much liability they will take on in the event that a company’s security screener or the airport is blamed for another terrorist attack.

Hiring a private company to conduct airport screening is attractive to many airports because they have seen poor or inconsistent performance by the Transportation Security Administration, which employs 45,000 screeners at more than 400 airports. Although the government raised the standards and recruited better-paid and better-trained employees at the checkpoints, several airports said the agency has been slow to hire enough screeners and has had difficulty retaining them.

Washington’s Dulles International, for example, suffers from a 21 percent attrition rate, among the highest in the country. Las Vegas’ McCarran International Airport, at one time had passengers waiting for three hours in security lines because the TSA did not have enough workers at the checkpoints to match the increase in traffic as travelers resumed flying.

Sometimes, the federal bureaucracy hinders operations, airports say. Every time a security screener leaves the job, the TSA headquarters sends its contractor to the city to set up a recruiting, testing and training program, which can take weeks. Even TSA managers stationed at each airport cannot hire or fire employees, even though the TSA said it is working to change that model.

“It takes so long to replace someone” who leaves the job, said Randy Walker, director at the Las Vegas airport. “It is so painful … and the local manager has no control.”

Security firms working at the pilot airports say they have more flexibility to hire and train employees quickly. None of those airports plans to part with the private companies.

Jackson Hole Airport director George Larson said he was pleased by his airport-run pilot program. He said he is able to turn a 10 percent profit by assigning screeners other airport tasks, such as cleaning and directing passengers to their gates, when the security lines are slow. Larson said he recently gave a talk about his security model at an airport conference in Las Vegas.

“It was standing-room only,” he said.

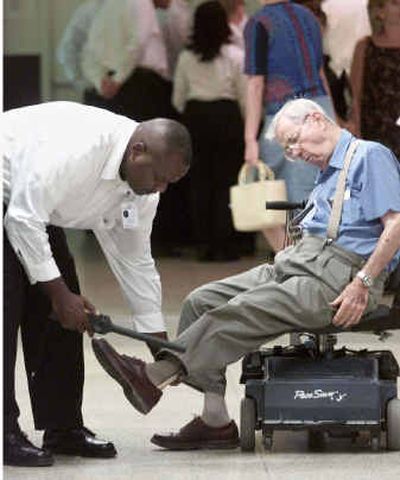

If private security firms win approval, they will be required to maintain the government’s standards, ensuring that each security screener speaks English, has a high school diploma or equivalent, and passes a background check.

Security screeners working for private firms must be paid a compensation package at least equal to the $12.50-an-hour wage plus benefits that the federal government offers, and the firms must give TSA employees priority in hiring.