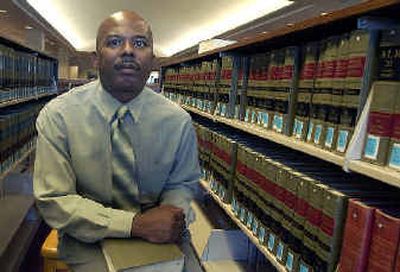

Defending death-row inmates a calling for GU law professor

A law professor at Gonzaga University is the last chance Frances Elaine Newton has to escape becoming the third woman executed in Texas since the state revived the death penalty.

Ken Williams, who came to GU two years ago, has been defending death-row clients for several years while also teaching law. It’s work that speaks to his empathy with the impoverished and his desire to operate as a check on the system, ensuring fairness.

Newton was convicted of forging her husband’s signature on $100,000 worth of insurance policies and using her boyfriend’s gun to shoot her husband, her 7-year-old child, Alton, and 21-month-old daughter, Farrah Elaine, in 1987.

Williams wants the court to order a retrial of Newton’s case and allow a jury to hear mitigating evidence that she was abused by her husband. Newton contends she’s innocent, that her husband and family were killed by a drug dealer trying to collect a debt from her husband.

A copyrighted Houston Chronicle story quoted Newton’s mother as saying, “I know she’s innocent. We’re a praying family, and we’re going to keep on praying.”

Williams has met with Newton three times.

“She’s a very pleasant, quiet person,” Williams said. “You’d meet her and think there’s no way she could have done this.”

Newton was jailed when she was 23. The petite woman is now 39.

“She does write me letters on a regular basis,” Williams said. Mainly, she’ll offer legal advice, potentially helpful rulings, anything that might help her case, he said.

There’s a strong chance she’ll be dead Dec. 1. The court set her date of execution earlier this month.

Working pro bono, Williams is crafting his request for a U.S. Supreme Court review of the case, which is due Aug. 18. All other legal venues have been exhausted. More than 10,000 cases are offered to the nation’s highest court and fewer than 100 are routinely reviewed, Williams said.

“I’ve seen a lot of good cases slip through the cracks,” Williams said.

Should Newton’s review be denied and her execution become inevitable, he plans to visit her one last time. He will not stay to watch her die.

“I don’t have any desire to see that,” Williams said. Until now, he’s only seen people die from serious illness.

Soon after Newton’s execution date was set, Williams received calls from journalists from around the country. He’s not received a call about the three men on death row he also represents.

“Society still has difficulty in accepting a woman killing,” Williams said.

Williams was recruited to Gonzaga University’s School of Law two years ago as part of an effort to bring in professors of varied experiences, said Gonzaga’s Academic Vice President Stephen Freedman.

“He’s a pretty serious guy,” Freedman said. “He’s a person who takes his research very seriously.”

Soon after settling into Spokane, Gonzaga President Rev. Robert Spitzer told Williams that he is the first tenured African American professor in the history of the Jesuit school.

Williams admits he thought he’d heard wrong at first. As far as anyone knows, it’s true, Freedman said.

Williams is taking a year’s leave in the fall to teach at Southwestern University School of Law in Los Angeles, a school that specializes in criminal law.

“I plan to come back,” Williams said, “unless President Kerry calls to appoint me to the Supreme Court.”

Williams worked previously at Texas Southern University’s Thurgood Marshall School of Law in Houston. Gonzaga gave him a chance to try something different, he said.

While in Texas, which has some 500 death-row inmates, Williams discovered he liked the death row appeals. The cases complement his sense of empathy imparted by his mother.

“My mother was real poor. She was a waitress (in a bar),” Williams said. “Before she died, it always seemed she had a really hard life. Ever since she died, I wanted to devote myself to people like her.”

Williams was 12 when his mother died of lung cancer in New Orleans. His father was a school principal.

His love of law came early in his college career at the Jesuit-run University of San Francisco. After graduating in 1983, he entered a top-10 law school, the University of Virginia School of Law.

“I didn’t come into my own as a student until college,” Williams said.

But once he understood the power of the law, he knew that was his lifetime path.

“I knew I wanted to help people. I wanted to help people who were downtrodden,” he said.

After graduating from law school, Williams returned to New Orleans. He did some public defender work and took a job with the National Labor Relations Board. He pursued an academic career after meeting a woman who would become his mentor, Ruth Coker, a fellow board member for the ACLU in Texas. After a few years, he was hired by Texas Southern University.

In Houston, he met a group of attorneys who specialized in capital punishment cases.

“It seemed like such an awesome responsibility to have someone’s life in my hands,” Williams said. “I get to help someone and be intellectually stimulated. It’s the best of both worlds.”

A federal judge did order a new trial for one of Williams’ clients, Howard Guidry.

Guidry was convicted of a contract killing of a woman involved in a bitter divorce. Williams argued that Guidry was tricked into confessing and was prosecuted with hearsay testimony. An appeal of the order for a retrial is pending.

“Anything goes in Texas,” Williams said. “A lot of these people get terrible representation.”

Probably the most frequent question Williams hears is, ” ‘How can you defend these people?’ “

There must be some checks on the power of police and defenders, he said. By giving the best possible representation, he’s ensuring the system works and remains healthy, he said. To date nationally, some 200 people on death row have been discovered to be innocent, he said.

The experience Williams receives from his pro bono work is then shared with his students, who pay to learn how to think about the law.