Exercise in teamwork

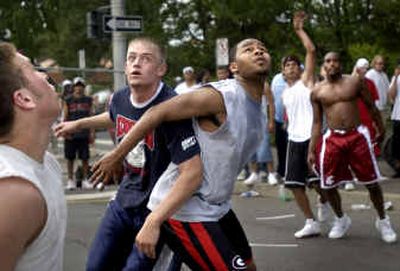

Down on the blacktop, with the crowds and the morning sun pressing in, tempers can be as hot as the asphalt.

An elbow sent Heather LaBrie, 13, sprawling to the ground. Her face turned red, but she dusted herself off and checked the ball in play.

Her team trailed 11 to 0. The high-school girls on the other team – schooled in backdoor cuts and screen-and-rolls – scored again and again. By the end of the first-round Hoopfest game, the other team was high-fiving and smiling. LaBrie and teammates quietly shook hands.

In some ways, it was a victory.

“Heather held it together,” said Bob Devine, a therapist at Spokane Mental Health. “In the old days, she would have been a volcano. But not today. I’m proud of her.”

For LaBrie’s team and three others composed of youths from Spokane Mental Health, the games had little to do with winning. They were exercises in teamwork and self-restraint.

“We call it life therapy,” said Tracey Tucker, a mental health therapist who started the teams three years ago. “These are kids who struggle to get along with each other. They won’t talk in a therapy room. They don’t have a lot of structure in their lives.”

For the past several months, they practiced basketball once week as a sort of recreational therapy. About 90 percent of the players have anger management problems. One youth, who suffers from severe anxiety, rocked back and forth at the first practice, his hands shaking. On the court, his confidence grew with practice. On Saturday, he knocked down a 12-foot jumper, one of his team’s few baskets.

Many of the players have washed out of traditional school sports programs, fighting with players and coaches. But at Spokane Mental Health, they have gelled into teams.

The team names aren’t flashy – Hoops I, Hoops II, Hoops III and Hoops IV. The players suggested other names, but “they weren’t socially acceptable,” Devine said.

Their growth as teammates is evident in small things. In a pregame huddle, the girls hugged and cheered. The boys patted one another on the back, and they crowded the curbsides to cheer for their teammates.

Often, basketball is an exclusive game, the realm of the big, the strong and the quick. But Hoopfest has swung wide the door, attracting thousands of players of all shapes, sizes and abilities.

Tucker saw an opportunity.

In the past two years, the teams have tallied a single victory in Hoopfest play. It came when two of the teams played each other. On Saturday, they struggled to compete with players well-coached, disciplined and athletic. The losses piled up. Twenty to two. Twenty to one. Twenty to zero.

But the teams raise an intriguing question: How do you win when you keep losing games?

Sometimes, Tucker said, it is enough to compete.

“I’ve been so proud of our teams’ sportsmanship,” Tucker said. “Our teams have behaved exceptionally. They have lost gracefully.”

In the hypercompetitive world of blacktop basketball – where thrown elbows and fouls can border on assault – the games can be shockingly rough, even for children and teenagers.

On first glance, it does not appear to be conducive to therapy. The players on Spokane Mental Health’s teams struggle with oppositional defiance, anger management and thought disorders.

But if the players can conduct themselves here, therapists reason, they can control their anger just about anywhere.

Take Tyson VanDinter, 12. Since third grade, he has struggled to control his temper. Now, as a 5-foot-9 center, he’s become a team leader. He’s quick and lanky, one of the most athletic players on the teams. Off the court, he has matured as well.

“He’s improved so much,” said his mother, Tiffany, as she watched her son’s game. “He doesn’t lash out at home like he used to. It helps for him to play with kids with similar issues.”

The teams have precious few plays.

Two are called Gigi and Fall Back Guard. There are several differing explanations for how these plays are executed. They prompt a broad discussion, some head-shaking and the tracing of routes on one’s palm.

“We just tell them to go for layups and try to get close to the hoop,” Devine said. “It’s free-flowing.”

The teams wear uniforms and basketball shoes donated by a local physician and a pharmaceutical company. The uniforms are brand new, complete with baggy shorts, but they lack the numbers and names that their opponents’ uniforms carry.

At Riverside and Post, Hoops II struggled Saturday morning to stay competitive. After making every practice, their best player – their ball handler and shooter – was unable to make the tournament.

The therapists said they could not disclose why, but Hoops II missed him.

Their opponents stole inbound passes, slapped away their shots and scooted past them for layups.

Yet the faces of the Hoops II team belied no anger or frustration.

“In P.E., I’ve played against some tough kids,” said Sean Morton, 13. “But it’s been awhile.”

His teammate, Kyle Fisher, 11, agreed.

“They were pretty good,” Fisher said. “But this is my first Hoopfest. Next year, I’ll practice more.”

On a downtown court Saturday afternoon, LaBrie and her teammates hugged and patted one another on the back as they got ready for another game. They’ll play again today.

“We just have to play hard,” said Kari Curbow, the team’s center.

“Then everything else will get better.”