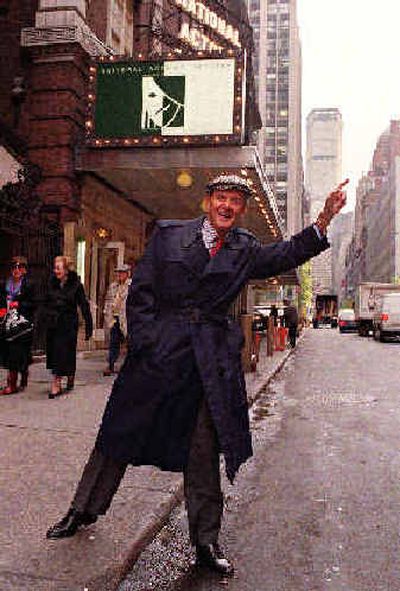

‘Odd Couple’ star Randall dies

When Tony Randall won an Emmy for playing Felix Unger in “The Odd Couple” just after the TV series was canceled, he deadpanned, “I’m so happy. Now if only I had a job.”

Randall actually never stopped working in a career that spanned six decades. He died of complications from a long illness at New York University Medical Center Monday at the age of 84. He developed pneumonia after undergoing heart bypass surgery in December. And he worked right to the end. A month before entering the hospital, the actor starred as Lamberto Laudisi in Luigi Pirandello’s play “Right You Are.”

The lights were to be dimmed Tuesday night in Broadway theaters as a tribute to a comic actor of rare talent and suave timing.

Randall’s gifts as a raconteur and a biting wit that was often self-deprecating put him in demand on the talk-show circuit. David Letterman made him a fixture with 70 appearances on the “Late Show.”

Randall will be forever identified with Felix Unger, the neurotic photographer condemned to share the slovenly lifestyle of sportswriter Oscar Madison (Jack Klugman) on “The Odd Couple.” The show, based on the Neil Simon play, ran from 1970 to 1975.

His other TV series were “Mr. Peepers,” costarring with Wally Cox; “The Tony Randall Show,” which cast him as a Philadelphia judge; and “Love, Sidney,” in which he played a single commercial artist.

In his movies, Randall had a particular flair for playing the fussy best friend, especially in the romantic comedies of Doris Day and Rock Hudson. It’s hard to imagine “Pillow Talk,” “Lover Come Back” and “Send Me No Flowers” without his pungent contributions.

He also fit the bill as a gray-flannel ad man playing against Jayne Mansfield in 1957’s “Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?” He was especially proud of “The Circus of Dr. Lao,” a 1964 fantasy in which he played multiple roles.

Randall was born Leonard Rosenberg in Tulsa, Okla., in 1924 and studied speech and drama at Northwestern University. He broke through on Broadway in 1941 with a role in “A Circle of Chalk,” but the war interrupted a fledgling career on Broadway, and he served four years in the Army Signal Corps.

When he left the service, Randall found radio and stage work, but it was “Mr. Peepers” that made him popular and, in turn, led to a nonstop schedule. It didn’t take Hollywood long to recognize his credentials in comedy, and he went on to make 25 films.

In 1991, Randall realized a long-held dream by putting up $1 million of his own money to found the National Actors Theatre, a nonprofit company that sought to bring the classical repertory back to Broadway on a consistent basis and at accessible prices. Its productions have included Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” and Ibsen’s “The Master Builder.”

When an ailing George C. Scott faltered during Randall’s 1996 production of “Inherit the Wind,” Randall appeared out of the audience, apparently knowing the role of Clarence Darrow from memory, and filled in. The company is now based in Pace University in downtown Manhattan.

A long-time opera buff, Randall entertained radio listeners’ questions on the Metropolitan Opera’s intermission quiz.

He was married to his first wife, Florence, for 54 years; she died of cancer in 1992. He later wed Heather Harlan, an intern at the National Actors Theatre who was 50 years his junior.

When Randall became a father for the first time seven years ago at age 77, he found himself the focus of a spirited debate about the wisdom of having a child so late in life. The Randalls were not deterred by the controversy and had second child in 1998.

Randall once gave a speech to the National Funeral Directors Association and urged that funerals should be a celebration of life.

“A touch of humor doesn’t hurt a bit,” said the man whose life certainly proved it.