Without a trace

KITTITAS, Wash. – Cody Haynes, an 11-year-old with the twinkle and smile of an all-American kid, didn’t come home for Thanksgiving.

He also wasn’t at his home on Main Street for Halloween.

Richard “Cody” Haynes Jr. hasn’t been seen since Saturday night, Sept. 11, when he vanished from his family’s home in an old two-story apartment, less than a block from the two-man Kittitas Police Department.

Now, as winter winds begin to blow down from the Cascades, there is widespread concern in this tiny central Washington agricultural community that the missing boy is dead, probably the victim of violence.

On the night the boy disappeared, his dad left the home at 2:30 a.m. for a 250-mile car trip, apparently driving throughout Eastern Washington and almost to Spokane, “looking for car parts,” police initially were told.

The boy was reported missing at 6 p.m. Sept. 12 – 18 hours after he was last seen, and after his father returned home.

Puzzled investigators have plenty of questions, but the missing boy’s dad and his live-in girlfriend, who once worked for Child Protective Services, are refusing to talk.

Kittitas Police Chief Steve Dunnagan says he fears the worst, but hasn’t asked for outside law enforcement help.

“It’s a small town,” the chief said. “We don’t have this kind of thing happen here – ever.”

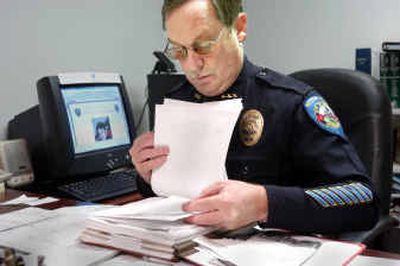

His department has received only eight tips, all unfounded, about the boy’s disappearance, Dunnagan said this week as he reviewed the file in his office. “We don’t have squat.”

The chief doesn’t think, at this point, that a stranger abducted the boy.

The boy’s natural mother, who has served prison time in Florida for child abuse and can’t legally have contact with Cody, has been eliminated as a suspect, Dunnagan said.

Shortly after Cody disappeared, state Child Protective Services workers removed his four sisters from the home after a suspected-child-abuse referral was made by the police chief. It was the third referral about suspected child abuse and neglect in the family’s home.

Dunnagan, who says he knows almost every kid in town, said he knew four girls lived in Haynes’ home, but the chief had no idea there also was a young boy who lived there.

“He was very sheltered, very controlled, very structured,” the chief said of the boy.

The family’s apartment on Main Street adjoins Sure Shot Gun & Pawn, Time Out Saloon and Kittitas Feed. There are no stoplights and very little traffic in the community, which is a mile off Interstate 90, nine miles east of Ellensburg.

A neighbor, 66-year-old Larry Oliver, said he’d occasionally see the Haynes children playing in the back yard, in between old cars, including a Kaiser that the boy’s father is restoring. “They’d never leave their back yard,” Oliver said of the youngsters, who were home-schooled.

The chief wants to talk to the missing boy’s dad, Richard “Rick” Haynes, a 43-year-old Ellensburg tow-truck operator. But Haynes and his live-in girlfriend, Marla Jaye Harding, both have retained a lawyer and are refusing to talk with investigators.

The police chief said he’s not labeling either Haynes or Harding as “persons of interest” at this point, but describes their response as “curious and strange.”

The investigator did find evidence of excessive corporal punishment and possible sexual abuse among the children, and referred that matter, as mandated, to the Department of Social and Health Services.

The abuse allegations are contained in a DSHS “dependency petition,” a sealed court document given to the Ellensburg Daily Record by Harding and Haynes as they “attempted to tell their story.”

Harding, 39, is a former Child Protective Services worker for the state of Washington who was fired in February 2001 and denied unemployment benefits, court records show. Harding was fired for misconduct, said DSHS spokeswoman Kathy Spears.

The ex-CPS worker and Haynes were the focus of a welfare fraud investigation when Cody was reported missing, the police chief and state officials confirmed.

“I ain’t talkin’ to you without my attorney present,” Haynes angrily said on Monday when tracked down in a “bull pen,” a holding area for wrecked and damaged vehicles, where he was working for D&M Motors in Ellensburg.

When a photographer took Haynes’ picture, he called Ellensburg police before yelling, “I’m going to call the NRA attorneys on you, too,” an apparent reference to the National Rifle Association.

An Ellensburg police officer who responded said Haynes’ privacy wasn’t violated and he had no right to object to his picture being taken because he doesn’t own the property where the encounter occurred.

When Haynes was told there is public interest in his missing son, he responded: “I’m not interested in talking about it. I’m not talking without my attorney present. No way.”

Asked if it was possible that his son was dead, Haynes quickly responded. “Oh, no, not a chance. He’s not dead. He’s not dead.”

He then walked away.

Harding didn’t answer the door at the Kittitas apartment. A handwritten note addressed to “Cody” was folded over and taped to a back door.

Haynes’ boss, Kevin Johnson, the co-owner of D&M Motors in Ellensburg, described him as “an exemplary employee.”

“He obviously has been upset with the situation of his son disappearing,” Johnson said.

But the employer acknowledged he and others in Kittitas County don’t have firsthand details about the boy’s disappearance, which have been largely kept quiet by the police chief.

The chief said the boy and Harding, who Haynes initially described only as his children’s “caregiver,” had a “heated argument” after Saturday dinner on Sept. 11. The boy reportedly refused a request to put leftovers away and do the dishes.

As discipline, Cody was ordered to sit in the kitchen until almost midnight when he was sent to a second-floor bedroom, without a door, which he shared with his dad, the chief said. His four sisters, sleeping in another bedroom at the other end of the apartment, were told to stay away from their brother’s room.

“About 2:30 a.m., Mr. Haynes told us he left the home to go looking for car parts,” the chief said, acknowledging that it would be difficult to find parts for a 1954 Kaiser in the dark.

Before he stopped talking, Haynes told investigators that his middle-of-the-night, 250-mile trip took him from Kittitas to Toppenish, to Yakima, to Naches. He took a wrong turn at the Vernita Bridge and eventually ended up on U.S. Highway 395 that took him to Ritzville and Interstate 90.

Haynes drove east at least to Sprague, in Lincoln County, the chief said. At some point, he turned around and returned west, before his 1984 Dodge minivan broke an axle at the Sprague rest stop.

He called a friend who drove to the rest stop and helped make the repairs, then returned to the Kittitas home about 4 p.m., “wondering, ‘Where is Cody?’ ” Dunnagan said.

The boy was reported missing to authorities at 6 p.m. on Sept. 12 by Harding, the chief said.

The chief was off Sunday and Monday, and didn’t get personally involved until Tuesday, Sept. 14.

“I asked him (Haynes) if it was possible if Cody stowed away in the van, and then got out, and he said it was possible,” the chief said.

Dunnagan returned to the family home on Sept. 17, hoping to ask the boy’s four sisters about what they had seen the night of the disappearance.

Harding answered the door and told the police chief he couldn’t question the girls. In front of them, she told the chief, “I’m not going to lose my freedom for anything,” according to the dependency petition filed by CPS workers.

When told she wasn’t the guardian or parent of the children, Harding instructed Haynes to deny the request, and he followed her instructions, the dependency petition said.

The police chief made a referral to CPS, saying his initial investigation uncovered evidence of child abuse – “inappropriate discipline” – in the home. The four girls were removed from the home on Sept. 21.

After preliminary, informal discussions, the chief and Kittitas County Sheriff’s Detective Jerry Shuart Sr. asked for a formal interview with Haynes on Oct. 22 – 41 days after his son disappeared.

Haynes showed up at the police station with Harding. When the chief asked for a private interview with Haynes, Harding objected, Dunnagan said.

“At that point, they ‘lawyered up’ and said they weren’t talking anymore,” the chief said.

Haynes and Harding didn’t show up for a communitywide search Sept. 15 when volunteers went door-to-door to 430 homes in the community of 1,135, passing out fliers with information about the missing boy.

His family did provide a pillowcase for the search, four days after he disappeared, but tracking dogs couldn’t find a scent trail, the chief said.

The dad and his girlfriend also didn’t attend a candlelight vigil organized by the community for the missing boy, Dunnagan said.

Word of the disappearance quickly spread.

Now the case is posted on the Web site of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

It’s also posted at the Polly Klaas Search Center, named in memory of the California girl whose body was found more than two months after she was abducted from her Petaluma, Calif., home by a knife-wielding intruder in 1988.

One psychic reportedly has said the boy is dead and his body will be found in the spring, according to word making the rounds in the community on Wednesday.

The police chief said he hadn’t heard that specific conclusion, but was aware that other psychics are predicting the worst. At this point, Dunnagan said he welcomes any help.

“Their behavior is definitely curious,” the chief said of the boy’s family. “It does make us ask, ‘Why does he have to have an attorney to help us find his son?’ “