Privileged Pilferers

Why would Tyco International Chief Executive Officer Dennis Kozlowski use company money to pay for a $15,000 poodle-shaped umbrella stand and a $6,000 shower curtain?

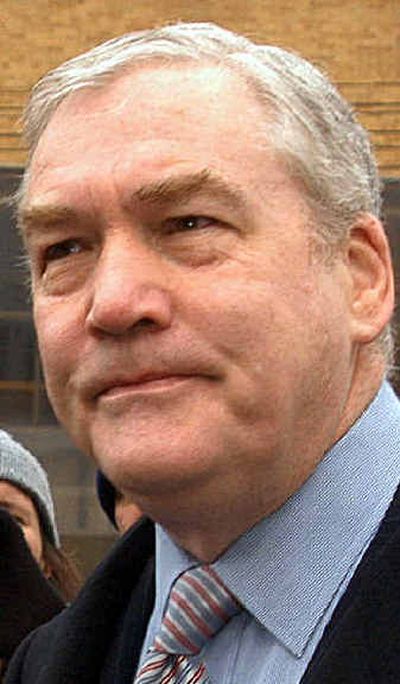

Why would Conrad Black, CEO of Hollinger International Inc., bill $2,400 in handbags to his newspaper publishing firm and have the company pick up the tab for his personal servants?

It is easy enough to understand why a financially strapped bookkeeper or a frustrated executive passed over for the top job might steal from his company.

But it is far more difficult to fathom why the pampered person at the top would plunder an enterprise that was paying him millions of dollars a year in cash and stock.

At the very least, spending corporate money on personal expenses risks an Internal Revenue Service audit. In the worst case, such behavior could cost a CEO his seven-figure job and land him in prison.

The simple answer is that some CEOs lose their sense of reality and feel entitled to whatever they can get away with, psychiatrists and corporate governance experts say.

Instead of thinking about what is fair or right, some CEOs look around to see what their peers at the top of the heap are getting in cash, stock options and perks, such as corporate jets and club dues. They want that — and more.

“They begin to feel that everything is going to be done for them, and they have the right to that,” said Dr. Robert Gordon, a psychoanalyst and partner in the Chicago firm Analytic Consultants, which works with business clients. “In our recent business culture, it has become more and more accepted to live like a potentate.”

Sometimes old friends can see the transformation with the most clarity. At his 35th high school reunion picnic in 1995, then-Enron Corp. Chairman Kenneth Lay bragged about how his wife exceeded her $2 million home-decorating budget in only a few months.

It seemed out of character, recalled one of Lay’s high school classmates. “Like the rest of us, he was brought up like normal folks. You just don’t bring those subjects up,” said Dan Simon, an attorney in Columbia, Mo. “He obviously had changed along the way.”

Last month, Black and David Radler, Hollinger’s former second-in-command, were accused of being the country’s latest example of “kleptocrats,” executives who steal from the companies that issue their paychecks.

“Behind a constant stream of bombast regarding their accomplishments as self-described ‘proprietors,’ Black and Radler made it their business to line their pockets at the expense of Hollinger almost every day, in almost every way they could devise,” according to a 513-page report prepared for Hollinger by Richard Breeden, a former chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

In Black’s case, the amount of money he took each year from Hollinger was determined by his exorbitant expenses, the report said.

It is not cheap maintaining houses and servants in London, Toronto, New York and Palm Beach, Fla., not to mention his wife’s well-documented fashion taste for Jean Paul Gaultier and Oscar de la Renta and a passion for expensive jewelry.

Then there were hobby-related expenses, such as the $8 million of Hollinger’s money Black spent on Franklin Roosevelt memorabilia. After Black was forced out as CEO of Hollinger in November, the company sold the FDR papers for $2.4 million.

Other recent examples of extreme executive privilege include Adelphia Communications Corp. founder John Rigas and his sons Timothy and Michael, who have been accused of improperly using company cash to pay for a personal masseur, 22 luxury cars, church dues, condo fees, 100 pairs of bedroom slippers, corporate jet rides for personal vacations and more.

Meanwhile, HealthSouth Corp. founder Richard Scrushy, indicted on charges of cooking the company’s books, is being sued by shareholders who say he stole corporate money to buy a Lamborghini, fly friends to the Grammy music awards on a corporate jet and promote a female pop band.

The standards are different, of course, for owners of private firms. They can take home every penny of profit and be justified in doing so. But it’s a far different matter when heads of publicly traded companies treat their firms as private piggy banks.

Even in cases in which the CEO is the majority owner, he or she has an obligation to act in the best interests of his co-owners, the individual investors who expect a return on their equity.

In extreme cases, some top executives believe that the rules of society do not apply to them, Gordon said. A grandiose sense of self develops, and they feel larger than life. They experience no remorse for actions that hurt others.

The mental health community has a word for such individuals: sociopaths.

Sociopaths appear normal, but they are manipulative and cunning. They often are charming and persuasive, and they seek out situations where their self-aggrandizing actions will allow them to succeed and be admired.

Many cult leaders fit the profile, but so do some out-of-control CEOs, mental health experts say.

“I’m sure there are many sociopaths who have headed corporations,” said Gordon.

Of course, no dysfunctional individual exists in a vacuum. In the corporate world, chiefs who are losing their bearings have boards of directors that are supposed to help them maintain perspective.

But boards often are stacked with friends of the top guy, which makes it hard — indeed, almost impossible — for them to say no, said Nell Minow, a corporate governance specialist.

The position of directors is even more awkward when the CEO owns a majority stake in the company.

“I hope everybody learns from Hollinger and Adelphia and Martha Stewart that if somebody asks you to go on a board where the CEO maintains voting control, the right answer is ‘no,’” Minow said.

It’s natural for a chief executive to lose perspective on what their compensation should be because many corporations these days throw tens of millions of dollars a year at their leader, shareholder activists say.

Out-size pay packages present a moral hazard to today’s corporate titans in America that does not exist in other countries and did not exist here a few decades ago.

A funny thing happens when people become rich beyond their wildest dreams, Minow said. “Sometimes they become even greedier.”

Whether a CEO starts out greedy, the temptation to enrich himself is there, and no one is likely to give them honest feedback about how their pay package plays in Peoria or anything else.

It happened to Minow when she became the head of a small company with about 25 employees, the opposite end of the spectrum from Fortune 500 behemoths.

“My predecessor’s last words were, ‘Watch how funny your jokes become.’ He was 100 percent right. After he left, no one ever told me the truth again,” she said.

When CEOs are not reined in, they may begin to measure themselves by how many summer homes they have, how many corporate jets they command, or how big and fancy their Gulf Streams are.

When the jig is finally up — the company has gone bankrupt, or the executive has been indicted — there is no reason to expect a teary confession or mea culpa.

CEOs accused of ruining their companies usually blame others for the problems or say the facts have been distorted. They rationalize their conduct and see themselves as victims of someone else’s crusade. For instance, Kozlowski, who resigned in June 2002, said he did nothing wrong because all his expenditures were authorized.

“Unless it’s some kind of public redemption, some of these big business guys are difficult to work with,” said Gordon. “They don’t want to change. They feel like there’s nothing to change.”

The Washington Post contributed to this report.