‘Play it right and with respect’

COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. – Ryne Sandberg was born and raised in Spokane, and we had a front-row seat in our living rooms for 15 years as his fame grew.

But in the end, it seems we barely knew him at all.

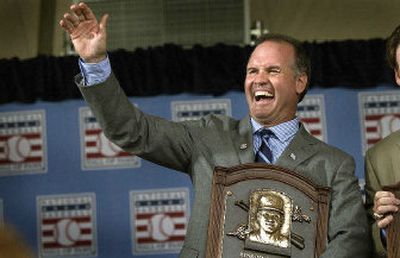

Quiet, reticent, almost colorless as a personality both in his boyhood on Spokane’s North Side and during his playing days with the Chicago Cubs, Sandberg was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on Sunday – and he brought the heat.

The unexpected result was one of the most memorable induction-day speeches in recent years – and a new shine on an old shoe.

Make that an old pair of spikes.

“I’m a baseball player,” said Sandberg, batting cleanup among Sunday’s inductees that included Peter Gammons and Jerry Coleman in the writers-and-broadcasters wing of the hall and one of the game’s consummate hitters, Wade Boggs.

“I’ve always been a baseball player. I’m still a baseball player. That’s who I am.”

That started in earnest at North Central High School in the mid-1970s and continued through a major-league career that came to an end in 1997. Sandberg retired – for a second time, after a year-and-a-half hiatus in 1994 and 1995 triggered by family issues and an impending divorce – as the career leader among second basemen in home runs (a record since broken) and fielding percentage.

But the baseball player took on a new role Sunday – that of the game’s conscience – with sharp criticism of modern players, their effort and approach.

“A lot of people say this honor validates my career,” said Sandberg. “But I didn’t work hard for validation. I didn’t play the game right because I saw a reward at the end of the tunnel. I played it right because that’s what you’re supposed to do – play it right and with respect.

“If this validates anything, it’s that learning how to bunt and hit-and-run and turn two is more important than knowing where to find the little red light of the dugout camera.”

After his speech, Sandberg was asked if he was referring to any player in particular.

“Who did you have in mind?’ he teased back.

“In general, you see a lot of that. I watch these games and see players self-promoting – they hit a home run, but their team is still down four or five runs, and here they are tipping their hat to the cameras because they hit a home run. It drives me nuts.”

But the assumption was that Sandberg was citing former Cubs teammate Sammy Sosa – the swing-away slugger who became a magnet for both team and public criticism last season before he was traded to Baltimore.

Sosa seemed to be in the cross hairs again when Sandberg recalled how Cubs broadcaster Harry Caray – “a huge supporter of mine” – used to say how nice it was that a guy who could hit 40 home runs and steal 50 bases (as Sandberg did in different seasons) also was the best bunter on the team.

“Nice?” said Sandberg. “That was my job. When did it become OK for someone to hit home runs and forget how to play the rest of the game?”

Forty-nine Hall of Famers – including Boggs – sat behind Sandberg as he said it, and many could be seen nodding their heads in agreement.

Induction day is rarely an occasion for broadsides or sermons. It is, mostly, a thankathon, with the inductees’ family and various mentors and teammates getting their due, and Sandberg didn’t shirk from that obligation.

Still, he threw a few high hard ones and he got off a joke or two, as when he thanked the Baseball Writers Association of America, which conducts the Hall of Fame voting.

“I think a large part of (my election) is the fact that I was a great interview and gave you so many quotes you could wrap a story around,” he cracked.

But it wasn’t that Sandberg was pretentiously colorful or glib. He didn’t ask Cubs fan Bill Murray – who sat in Sandberg’s special section and led the crowd in standing ovations – for comedy tips.

He was pointed, sentimental, sincere.

And it resonated with the Cubs fans who seemed to make up the loudest, if not the largest, part of the estimated crowd of 28,000 outside the Clark Sports Center, the third-largest induction audience in Hall of Fame history.

“We love you, Ryno!” came the shout during a pause not a minute into his speech.

“I love you, too,” Sandberg responded.

Not that Cubs fans weren’t caught off-guard, too.

“It was surprising,” said Mike Waller, who came from Oklahoma City and wore a replica of Sandberg’s No. 23 jersey. “He’s never one to cause a fuss or ruffle any feathers, and here he was calling out the modern players.

“I think he’s right. I think they do need to show the game more respect, and I think it was good that he spoke out about it. But it wasn’t anything I expected from Ryno.”

And it did upstage the embrace Sandberg reserved for his family, which included his wife, Margaret, the five children in their blended family, brother Del and his wife and children, sister Maryl Nance and 31 assorted uncles, aunts and cousins from California who turned the occasion into a reunion.

Sandberg acknowledged his deceased parents, Derwent and Elizabeth, and his late brother, Lane, early in his speech, and his sister spoke of how much the ceremony would have meant to them.

“My mom would have brought out the tissues already,” she said. “She’d be smiling ear to ear, and my dad the same. And if you asked them, I think they’d say they’re very proud – of all their children, because that’s what they always said. They would be very proud of Del for mentoring Ryne.

“And then I think they would be without words.”

Many expected Sandberg himself to be close to speechless on a day of speeches, but he had plenty of words – 23 minutes’ worth – and plenty of support, including a half dozen former Cubs teammates.

And as he did as a player, he sent them home with something to talk about.