NCAA rule cuts foreign legions

Michigan State basketball coach Tom Izzo thought his team had a budding star in Slovenian-born Erazem Lorbek in May 2003. The 6-foot-10 forward was coming off a stellar performance in the NCAA Tournament when he returned to Europe for a visit in May.

He never returned. Lorbek informed Izzo – who had no inkling it was coming – via phone he had signed with an agent and planned to play professionally, ending his college career. The Indiana Pacers drafted Lorbek in the second round of this year’s NBA draft, but he still is playing in Europe.

The Spartans have a Canadian this season, but Izzo is content to leave much of his international travels behind.

“I don’t see any sense, when you have (to recruit) three or four players a year, that you would recruit a European kid unless you have a special connection,” Izzo said.

Izzo might not be alone. The number of Division I players from outside the United States nearly tripled from 1993-2003, according to NCAA statistics. There were 392 during the 2002-03 season.

But the growth has slowed considerably the past two years, even while analysts agree the game is more popular internationally, and more international players are making the NBA. There were 396 international players last season, according to NCAA statistics.

ESPN analyst and former New Mexico, St. John’s and Manhattan coach Fran Fraschilla said an NCAA rule in which a player voids his amateur status if he plays on a team that includes players that are paid – even if that player doesn’t accept money or signs with an agent – is the main reason.

Many of those players are put in those situations as 13- and 14-year-olds, with nearly no knowledge of NCAA rules, Fraschilla said, adding domestic players who play on elite summer-league teams usually receive more material benefits.

“That rule has really limited the amount of kids that have come over here, particularly the last five years,” he said.

Fraschilla said overseas players looking to come here to improve their lives are most hurt. Jeronimo Bucero, a Spanish player he coached at Manhattan in the mid-1990s, would not have been eligible under current NCAA guidelines, he said.

“He came to us and wasn’t close to being the best player on the team,” Fraschilla said. “But he had a 3.97 grade-point average in international finance and opened us dyed-in-the-wool New Yorkers to a whole new world.”

Florida coach Billy Donovan lost talented forward Christian Drejer during his sophomore season in 2004, when Drejer abruptly left the team to sign with a professional team in Spain.

“A lot of these European teams have clubs that are paying players,” Donovan told the Arizona Republic earlier this year.

“For a talented young player to maintain his eligibility, that’s difficult. … I don’t want to say (the NCAA) doesn’t want foreign players, but it’s very difficult.”

Bill Saum, the NCAA’s director of membership services and head of its recently formed amateurism clearinghouse, cautions not to read too much into the slowing of international numbers. The amateurism clearinghouse is an attempt by the NCAA to make eligibility issues easier to understand, much like its academic clearinghouse was designed to make academic standards for players and schools easier to understand, he said.

“I would say we should pause before we look at a snapshot of just two years,” Saum said. “I don’t necessarily think the numbers have stabilized. … People are still looking for the international athlete, but they’re now looking more for the elite (international) athlete who can change programs.”

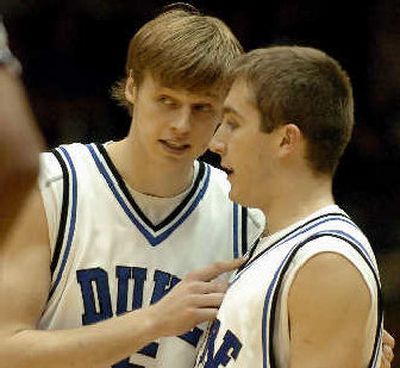

Top-ranked Duke, for instance, has two players in its highly regarded freshman class from overseas in Martynas Pocius (Lithuania) and Eric Boateng (England). Indiana has Ben Allen (Australia) and Cem Dinc (Germany).

Saum said the NCAA has been willing to work with international players who may have inadvertently broken rules as a youngster. That player may be granted eligibility but have to sit out a certain amount of games, for instance.

“The ones that we’re going to take significant pause over are the ones who have signed contracts, have drawn a salary and have signed with sports agents,” he said. “I think everyone agrees those are clearly professionals, whether they’re domestic or international players.”

But no matter the rules, international recruiting is here to stay. Top-level programs want the best players, no matter their country of birth. Teams struggling must look to non-traditional areas to harvest talent.

“If there’s a kid in the Midwest, for instance, and other schools in the Big Ten want him, I might be third or fourth getting on the list,” said Northwestern coach Bill Carmody, who usually has at least two international players in his starting lineup.

“If you’re in a conference and you’re not the top dog, it’s tough to recruit the same area. That’s true with a lot of teams across the country.”