Paperback market is going premium

NEW YORK — Slow sales and an aging market have the publishing industry thinking about upsizing — at least when it comes to paperbacks.

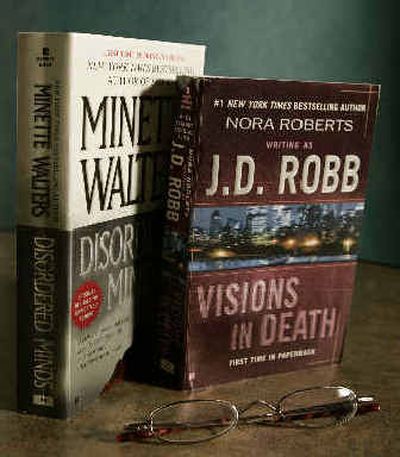

Mass market paperbacks, those pocket-sized best sellers available everywhere from airports to drug stores, are on the decline, apparent victims of increased competition and the squints of baby boomers who value larger print over lower prices.

“Many people over the ripe old age of 40 are starting to have trouble reading, and reading mass market books has become very difficult,” says Jane Friedman, president and CEO of HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

“The format’s been down a little bit, and I definitely think there’s room for innovation,” adds Allison Elsby, genre fiction category manager for Borders Group Inc., the superstore chain.

Mass market books remain a vital, billion dollar product, enabling readers to snap up cheap, portable editions of such favorites as Dan Brown’s “Angels and Demons” and John Grisham’s “The Last Juror.” But according to the Book Industry Study Group, a nonprofit research organization, annual sales have dropped by 65 million over the past five years, from 600 million in 1999 to 535 million in 2004.

In response, publishers are trying out a new paperback format, so new they haven’t even agreed on a name for it. Penguin Group USA calls it “Penguin Premium.” Simon & Schuster Inc. and Hyperion still just think of it as “new.”

The new paperbacks will be at least a half-inch taller than mass market books — big enough to make the books more readable, but small enough to fit into pockets and existing store racks. In both size and prize, they will stand midway between mass market books and “trade” paperbacks, which are the same size as hardcovers.

This summer, for example, Penguin will issue a “premium” edition of Clive Cussler’s “Lost City,” which came out in hardcover last summer. The new format will have a suggested price of $9.99, about $2 more than a typical mass market book and about $4-$5 cheaper than a trade paperback.

“We think it will be a more comfortable reading experience, but still at an affordable price,” says Leslie Gelbman, Penguin’s president of mass market paperbacks.

Simon & Schuster and Hyperion are also planning books in the new format, although both declined to list any specific titles. Hyperion president Bob Miller called the paperbacks “a smart experiment,” while Simon & Schuster president and CEO Jack Romanos said the books would hopefully “bring back former readers.”

Small print is cited as a primary reason for the mass market blues, but publishers and booksellers also note the increased availability of hardcover books and trade paperbacks, which now turn up in supermarkets and other venues where only mass market books were once sold. And Barnes & Noble Inc., which has long advocated lower prices, said the format is no longer the bargain it was decades ago.