Congolese watch the aid go elsewhere

KINSHASA, Congo – Even now, as thousands of children die each week from drinking dirty water and not having enough food, and the people of once-thriving communities hide like the hunted in the forests, the Congolese expect little from the world’s big spenders.

But as Congo watches the global scramble to raise billions in aid for victims of the Dec. 26 tsunami, many here wonder why Asian suffering stirs action while African suffering is greeted largely with apathy.

The New York-based International Rescue Committee says nearly 4 million people have been killed in Congo since the start of war in 1998, most from war-induced disease and starvation. Fighting persists in the county’s east – the epicenter of the war – and 1,000 are dying each day, half of them younger than 5.

The tsunami, in comparison, killed an estimated 150,000 as of Friday. The disaster was a sudden scourge of nature, while Congo’s toll has accumulated slowly, at the hands of man.

“Over the last six years, millions of people have died here from this war,” said Kudura Kasongo, spokesman for President Joseph Kabila. “In Asia, they’re dying too, and getting money. Why is this?”

“In Asia, Westerners are also dying alongside them, perhaps that’s why,” Kasongo said.

Led by $810 million from Australia, the victims of the Indian Ocean tragedy have received a total of nearly $4 billion in pledges.

According to the IRC, international humanitarian aid for Congo was $188 million – roughly $3 per person – in 2004.

“Asia’s crisis is temporary, but here we have a permanent catastrophe,” said Ingele Ifoto, a government minister who recently headed a program to return 32,000 displaced people from Congo’s dense northern Equateur province. Many were found roaming naked through the wilds, their clothing rotted off.

On Thursday, British Treasury chief Gordon Brown called on the world’s richest nations to contribute an additional $50 billion to the world’s poorest countries, particularly in Africa.

The same day, Prime Minister Tony Blair described the dire humanitarian situation in Africa as “the equivalent of a man-made, preventable tsunami every week.”

“Outside of the tsunami areas, I would say Congo is the one area in the world where most people die of neglect and lack of attention and lack of presence of the international community,” U.N. humanitarian chief Jan Egeland said.

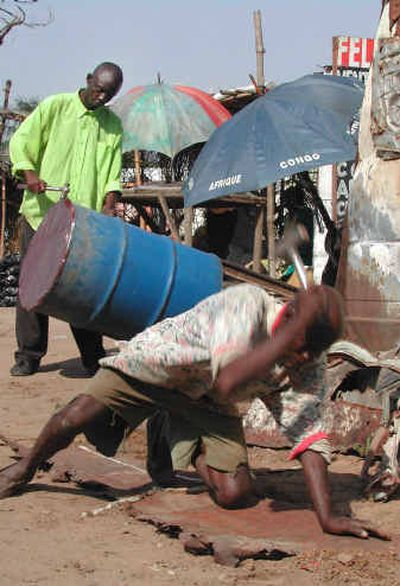

In Congo’s hardscrabble capital, Kinshasa, decades of government corruption and broken promises have taught its people a thing or two.

“I’ll tell you why no one gives Congo any money,” said Ponce Mondano, a mason at a market near the Congo River. “Because every time they do, the government just steals it.”

Africa has had its share of the world’s sympathy.

In 1984, Live Aid brought significant attention to victims of Ethiopia’s famine, and world leaders have recently spoken out on behalf of Sudan’s western Darfur region, where ethnic conflict has displaced an estimated 2 million people since early 2003 and killed tens of thousands. The world response to Ethiopia helped prompt long-term improvements in famine-warning and food-reserve systems, international officials say.

The U.S. Agency for International Development spent $54 million on Congo in 2004. The request for 2005 is $32 million. The decline mostly reflects an elimination of food aid.

But world attention to Congo’s war has always lagged.

More than 2 million displaced people are scattered across the country, living in squalid camps, or within the world’s second-largest rain forest, where rogue militias cut them down.

In one part of eastern Congo, renewed fighting last month between loyalists and dissident, former rebel soldiers emptied communities and caused about 150,000 to flee into forests.

U.N. peacekeepers established a six-mile buffer zone to separate the two warring sides, but it hasn’t stopped gunmen from venturing in.

In towns like Walikale, south of the buffer zone, the entire population has fled four times already this year.

In nearby Niabiondo, the only people left on the streets are loyalist government Mai Mai soldiers with Kalashnikovs and machetes, waiting for their next opportunity to battle former rebel troops, allies of neighboring Rwanda.

Doors are missing on every house and hut, ripped off after their owners fled. Most of the town’s residents now live rough in the jungles, with no humanitarian aid in sight.

“We need medicine and health care, but nobody wants to approach us,” said Kubuya Doole, 30, who appeared from the forest on a road outside town looking for food. She was filthy and hadn’t eaten for days.

“We’ve been in the bush two weeks,” she said, “wondering the whole time what the world thinks about us.”