Brady overcomes average skills with superb grace under pressure

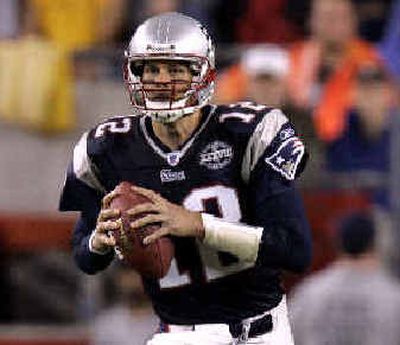

Tom Brady presents the experts with a chronic problem: He’s invariably better than they say he is. This is partly a problem of articulacy. In appraising Brady, we tend to employ one of the more ill-used and dog-eared words in sports: intangible. This is a pretty weak description, and it doesn’t really explain why a 27-year-old with average talent and few apparent muscles is one of the most successful pressure players, with a 7-0 record in the playoffs.

All over the NFL there are failed seers and blind palmists when it comes to Brady. The scouts? Those brilliant evaluators thought so poorly of him that he was the 199th player chosen in the draft, out of Michigan in 2000. The commentators? They’re the ones who said he had no chance against Peyton Manning and the Indianapolis Colts, and some of them are saying he has no chance against the Pittsburgh Steelers and strong-armed Ben Roethlisberger, either.

We get lulled by Brady’s head-ducking reticence, or distracted by his cleft chin, when he said, “If I don’t really work at it, I’m a very average quarterback.” But if Brady wins again this weekend, it will be time to throw away the modest qualifiers, and the silly preoccupation with his looks, and state that he has real greatness in him.

We talk about pressure a lot, but we hardly ever seriously examine it. It’s why nobody has quite put a finger on what it is Brady does so well, or how he does it. Statistics are irrelevant in trying to explain him; it’s just not useful to compare him to his fellow NFL quarterbacks. The only statistic worth mentioning is that on 15 occasions, he has led his team on game-winning, fourth-quarter drives, two of them in the Super Bowl. For that reason, maybe it’s more useful to look at another group of people when talking about Brady: people who ace the SATs.

He tests well.

“The thing that gets the best of most players is their inability to deal with anxiety,” said former quarterback turned CBS commentator Boomer Esiason. “That’s why guys have not lived up to the expectations. They can’t handle the basic game itself, let alone the biggest moments in the games. Brady is human, so you know he has the demons we all had when we played. But somehow he’s been able to capture those demons and play free of mind. Everybody has anxiety, but his never seems to get the best of him.”

Pressure has actual physical effects. Sociologists and behavioral psychologists know without question that pressure or “threats” affect performance in myriad ways for all of us, not just NFL quarterbacks. Studies have shown that fear of failure can drive down test scores of the best math students. Administer a practice SAT problem to a group of math students and they tend to score higher. Tell them it’s the real SAT and that their scores will affect their college admissions, and scores tend to go down.

Anyone who has taken the SATs has an inkling of what a quarterback feels in the pocket. Shallow, butterfly breath. That ice floe of anxiety in the stomach. The sudden inability to think and employ basic skills you learned in grade school. Now add a 300-pound lineman bearing down on you, with just seconds to make decisions.

One of the things that happens when we falter under pressure is that our bodies literally betray us. When we are threatened, we are partly at the mercy of our biochemistry. Behind every emotion are molecules. “There is a genetic component to performance anxiety,” said Eric Morse, of the International Society of Sport Psychiatry. Adrenalin is pumped from the pituitary gland, heart rate and blood pressure go up, and blood is shunted to the bigger muscles in your body — this is standard fight or flight response. “But sometimes, for some people, they overfire,” said Morse.

This can be fatal for a quarterback. While blood surges to your larger muscles, less goes to your hands and feet. Fine motor control is affected. “Touch on the football can be lost,” Morse said. Remember Manning, his feet stuttering like jackhammers, struggling to control his throws?

Simple acts you’ve performed unthinkingly your whole life suddenly, under fear of making a mistake, become studied. Now your mechanics are off, as well as your touch. With shallow breathing and an elevated heart rate, less oxygen flows to your brain, and your decision making is altered.

But if your constitution is able to tolerate all those firing chemicals and blood surges, as Brady’s apparently is, you perform better. In his case, much better. So while Brady may not be bulging with muscles or arm strength, he may have a less obvious but important physical gift: a fortunate temperament.

Think about it. How many times have you seen Brady make a truly bad decision or poor throw under pressure? Last week, he had third-and-10 on the Patriots 6. He completed a perfect pass to Kevin Faulk for a first down that probably sealed the win. “The number one thing is, he’s never overwhelmed in the pocket,” Esiason said. “His anxiety doesn’t rush him to make bad plays. He’s not so flawless that he doesn’t have a bad game. But his pocket presence is an amazing thing. Compare him to Peyton Manning, who was all over the place. Brady is the model of composure and poise. And he’s always that way.”

Response to pressure, of course, is not entirely genetic. It’s also about a self-possession learned through discipline and experience. According to Morse, temperament can be refined, it’s also a mental “skill” and you can practice it. As a consultant to University of Maryland Medical Center, Morse works with athletes on various ways to control their responses. Breathing exercises, for instance, can stop the cascade of hormones. You can also learn how to fix “cognitive distortions” that occur under pressure. A common cognitive distortion is “catastrophizing,” which is to immediately think of the worst thing that could possibly happen.

Brady’s greatest strength may be his avoidance of those cognitive distortions. He implements a game plan and makes the right throws without worrying unduly about consequences. “He’s focused more on the process as opposed to the outcome,” Morse said. “When you’re not worried about throwing an interception, you just focus on throwing it where it’s supposed to be thrown.”

For whatever reason, whether chemical or cognitive or some combination, while others dread pressure, Brady thrives on it. Consequences to him are performance enhancers. In the postseason, “your mistakes are magnified,” he said. “You’re playing the best teams in the league, teams that have played the best under pressurized seasons. If you take a bunch of sacks, throw an interception, the other team is so much more capable of taking advantage.” But that doesn’t make him nervous? “The nerves come from not knowing what to do,” he said. “When you know what you can do, that’s supreme confidence. It’s like in school when you know all the material before a test.”

Now that’s an interesting comparison. So how did Brady do in school? Ask him, and he tosses his head back and laughs. “I wasn’t as good as my postseason record,” he said.