Indians to get resting place

Spokane’s urban Indian population can soon choose to be buried in an all-nations Indian cemetery that will be ready in January.

The All Nations New Beginning cemetery is the first official burial site of its kind in Spokane – in modern times of course. There was a time when all the land in Spokane was occupied and used solely by American Indians in pre-settler history.

Since settlement and the formation of defined Indian lands, many Native Americans have chosen to be buried on their home reservations. As some families moved off the reservations, they made permanent lives in Spokane. Until now, there wasn’t a cemetery in town dedicated to American Indians.

“My whole life is here, but I will still be with my people,” said Julie Sleep, a Cheyenne Indian, who plans to be buried at the new cemetery. She’s a pre-planning specialist at Fairmount Memorial Association, which will be caretaker at the new cemetery.

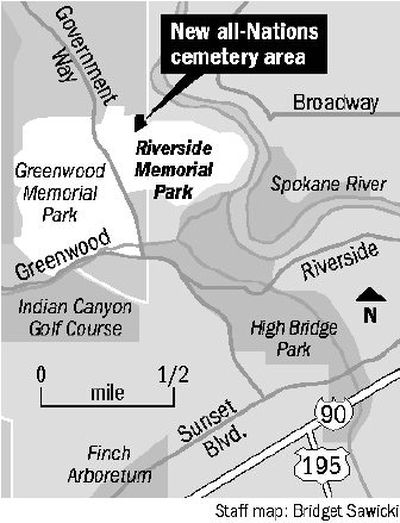

For $700, Indian people who choose to be buried here can be placed among other Indians on a bluff in Riverside Memorial Park. The idea is to begin with at least 30 plots. Up to 200 plots can be added, and more depending on demand.

Sleep had been working with a small group of volunteers in forming the idea. She’s also gotten support from James Konitzer, marking director for Fairmount Memorial Association.

“We consider our cemeteries community owned,” Konitzer said. “Our philosophy is memorialization whether it be cremation or traditional burial.”

The idea originally came from Marge Stasso, a Kootenai from the Salish-Kootenai Indian reservation in western Montana. She left the reservation to live on her own before she was a teenager. Her father was killed when she was 3.

Now, at age 78, Stasso is seeing a long-held dream come true.

The idea jelled for her when she was working on arrangements for a relative’s burial and she saw that different groups had their own areas. In the Fairmount Memorial Association cemeteries, the Chinese had a section marked off with round stones. The Baptists, Jews and Mormons also had a section dedicated to their faiths.

“It’s a beginning,” Stasso said while standing on the 50-foot-by-100-foot section of land facing south. Foliage and small pines covered the undeveloped land.

Stasso also envisions a longhouse on the land for people to hold burial ceremonies that are true to their particular tribe’s traditions. She hopes the lodge will come in time.

As she walks over the uneven ground, she reaches down for a fuzzy green plant that she holds up to her mouth and explains that the leaves were once used to help people with sore jaws. The whole site is covered with medicines, she said.

She takes the hands of the three women with her and falls silent as Sleep leads a prayer asking that the idea be successful.

“I think this is a huge deal,” said Toni Lodge, when she heard about the project. She is director of the NATIVE Project, a nonprofit organization for American Indian families in Spokane.

The cemetery is a much needed addition to the community, she said. Some American Indians don’t have close tribal connections and their tribes won’t pay for them to come home when they die, she said.

“There’re so many people here who die and don’t have the cash to go home,” Lodge said. “A lot of tribes don’t have the money to pay for that trip home.”

Lodge said the urban Indian population in Spokane is 10,212, representing 85 tribes in the United States and Canada.

Some had come for the good health care in Spokane. Others lived on the streets. Some have been here since World War II.

Now they’ll all have a place of peace to rest, Sleep said.

“All nations can come to rest and come together as one,” Sleep said.