Whitney’s high

Any excuse will do for Edwin “Wyn” Hill when it comes to plotting an adventure with his family. But now that his oldest daughter, Whitney, has branched off to college at Whitworth, the Spokane financial planner is rising to the challenge of being even more creative. “It’s fun to set some goals that can become high points (in our relationships),” he said in February after faxing wilderness permit applications to the Inyo National Forest in California. In the lower 48 states, there’s no higher point than Mount Whitney, he pointed out. “I’ve always wanted to take my Whitney to Whitney,” he said, clearly delighted that he’d conjured up a justification even more compelling than “Because it’s there.” On Sept. 20, the Hills were boosting their relationship up a serious mountain.

Mount Whitney is the highest peak in the contiguous states, angling up from the Sierra Nevada Range to 14,497 feet. The barren granite mountain was first climbed in 1873 by three local fishermen.

Nowadays, about 30,000 people a year attempt to climb Whitney. The number would be considerably higher if the Forest Service hadn’t set a quota to keep human impacts in check.

The overall odds of getting an overnight permit to climb the peak in the lottery drawing are roughly 2 to 1. The odds are better if you apply for shoulder-season dates or harder routes or do the 22-mile round-trip odyssey in a single day. The odds are worse if you limit your options to the main trail during the peak season from late June through early September.

Even though there’s a trail to the top that can be negotiated in sneakers in the right conditions, only about a third of the climbers succeed, according to summit register counts.

This year, about 9,700 people have signed in at the summit. That’s down about 500 hundred from recent years, probably because of the huge snowpack in the Sierras that delayed the hiking season, Forest Service rangers said.

Altitude is the main culprit in keeping success rates around 30-40 percent, and the Hills didn’t underestimate it.

They arrived in Lone Pine, Calif., elevation 3,733 feet, and allowed themselves two days to acclimate before the date on their climbing permit. They increased their exposure to rarified air with a dayhike in the Sierra Nevada from Horseshoe Meadow up to a head-throbbing, lung-stressing 11,000 feet.

Then they came down to Whitney Portal trailhead and camped at the relatively comfortable elevation of 8,300 feet. There they rented the required bear-proof food storage containers at the small but popular Portal Store.

The following day, they took their time backpacking up from the end of the road, into the John Muir Wilderness, through the scattered wildflowers and weathered foxtail pines, past gin-clear mountain lakes and into the naked granite above timberline.

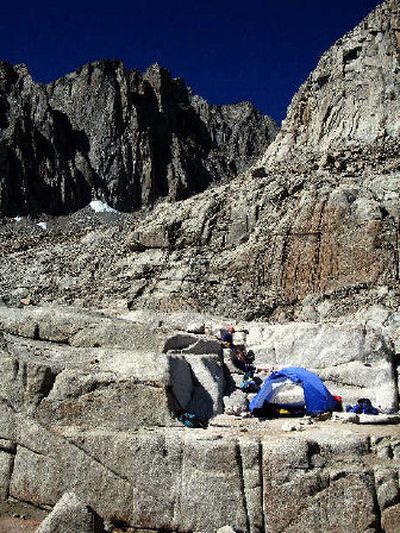

They pitched their tent a short way from the transient nylon village at Trail Camp, where the only lingering structures are the stone walls stacked by climbers to protect their tents from wind and the solar latrine.

However, the latrine, as usual, wasn’t able to keep up with the season’s demand. By September, every climber was given a “Wag Bag” for packing out his own human waste. The sturdy bags contain a chemical that deodorizes feces and transforms it into a gel.

If your tail isn’t dragging on Mount Whitney, it’s probably Wagging.

The Hills joined a couple dozen other Trail Campers as they lounged, read and drank plenty of water at 12,040 feet to give their bodies one more acclimation day before the ascent into another world.

At 14,000 feet, the average hiker performs at about 60 percent of normal sea level capacity.

In many cases, however, high altitude can be incapacitating.

The sometimes insidious symptoms of altitude sickness can vary from person to person and trip to trip. The ailments range from lethargy and mild headache to much, much worse. Cerebral edema contributed to the death of a Mount Rainier hiker at the seemingly innocuous elevation of 7,000 feet.

“We don’t keep records on how many people get altitude sickness,” said Nancy Upham, Inyo National Forest spokeswoman. “Most people recognize the symptoms and take care of it themselves by heading down before they get too bad off.”

The Hills woke at 4 a.m. on summit day to get a head start on the possibility of afternoon thunderstorms, the other major threat to Whitney climbers. They were on the trail at 5 under a full moon that illuminated the granite landscape in a surreal blue-gray hue. They never had to switch on their headlamps as they headed into the 99 switchbacks up to the Sierra Nevada crest and the border with Sequoia National Park.

Whitney’s hands were numb with cold when they started, but soon the climbers settled into a steady pace that left them gobbling up elevation and glowing with more than warmth. The wind was unusually calm and the mountain was silent, aside from the crunch of grit under their boots, the click of hiking poles on the trail of stone and the occasional sniffle from cold noses.

They reveled in the quiet until sunrise flooded the mountain with orange, the full moon still beaming above. “It doesn’t get any better than this,” said Wyn, snapping photos.

At least 13 routes lead to the summit, ranging from technical rock climbing to weeklong backpacking trips. The 11-mile Mount Whitney Trail from the trailhead to summit is the easiest and most popular route. The original trail was built in 1904 by the citizens of Lone Pine who could see the tourism potential.

Indeed, the tiny town the size of Davenport, Wash., lies 10,000 feet below in the shadow of Whitney and includes three sporting good shops in a block, plus a main drag with five motels, numerous busy restaurants and two federal visitor centers.

The Forest Service re-aligned and improved the trail after World War II, blasting some sections out of a rock buttress. The route is extraordinarily well-maintained, complete with a chain railing that helps climbers negotiate a 40-foot stretch of trail on which seeps often freeze into a scary bulge of solid ice along a vertical ledge.

People seeking solitude resort to more difficult cross-country travel, such as the Mountaineer Route that John Muir pioneered two months after the first ascent in 1873.

But the Hills found plenty of wilderness on the main trail.

From Trail Crest, they traversed a rocky ridge for 2.5 miles. They looked down on alpine lakes and through a series of rock needles to the west and open slots or “windows” that let the wind and morning sunlight stream in from the east. Despite a few photo frenzies, the father-daughter team was high-fiving on Mount Whitney’s summit before 8 a.m.

A handful of climbers were already on their way down, leaving only two other persons with the Hills on the top of one of American’s most-climbed major peaks.

Mount Whitney was named in 1864 by a field crew working for the California survey initiated by JosiahWhitney, a former Harvard geology professor who became the California Geological Survey chief. He had organized a team of geologists and geographers to survey the entire state of California.

The Sierra Nevada Range runs north and south and forms California’s backbone. It includes 11 peaks higher than 14,000 feet. Five of them are within a six-mile radius of Whitney. Whitney follows the flow of the terrain, with the summit flanked by a broad gentle slope to the west and a vertical cliff to the east.

The Sierra Nevada, which includes three national parks — Yosemite, Sequoia and Kings Canyon — is considerably larger than the Alps that stretch through France, Switzerland, Austria and Italy.

The Hills tried to absorb as much of this stunning landscape as possible during a wonderfully clear, calm morning on the top of their game.

For a while, the only distraction from the view was a rosy finch pecking around their boots looking for snack crumbs.

Suddenly a climber popped up out of the thin air, his head at Wyn’s knee-level as he paused to catch his breath after making a solo ascent of the mountain’s precipitous east face.

Then a few more hikers showed up from the main route. The rush had begun.

The Hills were among the first eight to sign in that day at the summit register, which is attached to a small, cold, stone hut built in 1909 by the Smithsonian Institution for scientific research. Dozens more summiteers would follow.

While Whitney Hill had learned she has a remarkable capacity for climbing in the thin air above 14,000 feet, going down was surprisingly effortless compared with going up. The Hills spread the word of encouragement as they descended, passing a stream of climbers, some of whom looked as though each step might be their last.

“Is it worth it?” a woman asked without lifting her eyes from the trail.

“Yes! Absolutely!” Wyn encouraged.

Some climbers avoid this parade of the human condition, but the Hills found new faith in humanity at the sight of young and old, fit and not-so-fit pilgrims stepping out of the comfort zone for the dream of a Whitney high.

For the Hills, the experience was so perfect, they decided to add a low point by driving 135 miles from Lone Pine to Death Valley. Within 25 hours of standing atop Whitney they were flooding their lungs with oxygen and the lowest spot in the country at 282-feet below sea level.

Now Wyn Hill has to top it with Whitney’s two siblings.

Second daughter, Paige, may want to set her sights on the peak of that name in Antarctica.

And by the time youngest daughter, Hayley, comes of age, maybe they’ll shoot for the comet.