Congo care package

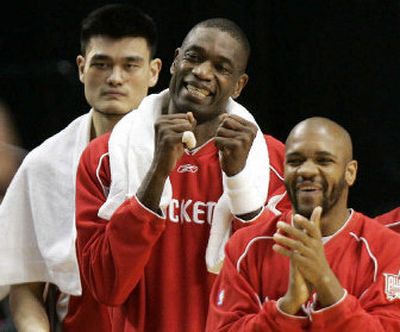

After 15 years in the NBA, Houston Rockets center Dikembe Mutombo has the means to live the life he could only dream of growing up in Kinshasa, capital city of Congo. Mutombo, who will earn $2.2 million for the upcoming NBA season, is able to own multiple homes and drive luxurious cars. But the memories from his youth compel him not to forget his impoverished homeland, the former Zaire.

He paid for the Congolese women’s basketball team’s trip to the 1996 Atlanta Olympics and for the track team’s uniforms and expenses. He regularly sends medicines and equipment back home.

Mutombo’s most daunting undertaking has been construction of the 300-bed Biamba Marie Mutombo Hospital near Kinshasa, where the ceremonial opening is Sept. 2. The hospital hopes to receive patients a few weeks later, pending the last shipment of equipment and arrival of a sterilizer. He has given $15 million of the $29 million cost.

The “air of expectation” at the neighborhood or ward level is incredible, said Joyce Hightower, a Kinshasa-based physician who is a consultant to Mutombo’s project.

“This is what they are calling ‘a jewel,’ an institution of this quality,” she said. “It is giving priority to the people who are the poorest,” what Mutombo desires most.

Mutombo is $7 million shy of the building’s cost and must still raise money to cover operating expenses, which he estimates will be $2 million-$2.3 million a year.

That is why today he is launching a campaign to recruit 100,000 donors who would pledge $10 a month to his foundation for one year. “With this we can reach even the (lower income levels) of the American public,” he said.

“Dikembe could have enjoyed all the luxuries and creature comforts of (the United States) and not been concerned,” said TNT basketball analyst John Thompson, Mutombo’s coach at Georgetown University. “I’m proud … that he’s applying his education, applying the values his parents taught him and helping people.”

Mutombo said the hospital, named in memory of his mother, is in keeping with an African proverb: “When you take the elevator up to reach the top, please don’t forget to send the elevator back down so that someone else can take it to the top.”

The project, begun in 1997 through the Dikembe Mutombo Foundation, is Mutombo’s way of sending the elevator down. “People in my country are dying,” he said, “and I want to save them.”

Dr. Mimi Kanda, director of the National Center of Minority Health and Health Disparity at the National Institutes of Health, left to be Mutombo’s senior adviser for the project. She said life expectancy is 45-47 years in Congo, 79 in the United States. One in five babies, she said, doesn’t reach a fifth birthday there.

Kanda, a pediatrician by training, said children in Congo are still dying of preventable diseases such as malaria, polio and measles. Patients needing magnetic resonance imaging exams or CT scans must travel to South Africa or Europe.

“This hospital is definitely a godsend for the people of Kinshasa,” said Faida Mitifu, Congo’s ambassador to the United States.

Initially, Mutombo encountered numerous “bumps in the road,” even from his NBA brethren. Ground was broken in 2001, but construction didn’t start until 2004 because donations came in at a slower pace than he anticipated, especially from other NBA players.

“My expectations were a little bit higher,” he said. “I was looking at it to be done through the NBA. It might have been a mistake on my part by feeling that way. It was not an obligation or a duty … to commit to my cause. But the guys have given me a lot of money.”

The players have donated roughly $500,000, and the players’ union another half million. Owners have contributed $700,000. Mutombo would not say how much the league, as an institution, has given.

Mutombo learned about his country’s medical deficiencies firsthand when his mother died of a stroke in 1998. The country was in civil unrest, and she was unable to get to a hospital because of a curfew in effect.

His hospital is on a 12-acre site on the outskirts of Kinshasa in Masina, where about a quarter of the city’s 7.5 million residents live in poverty. It is minutes from Kinshasa’s airport and near a bustling open-air market.

Initially, the emergency room, operating room, intensive care unit, outpatient care and internal medicine department will be open. The infectious disease and pediatrics wards are expected to open within two years. Some beds from internal medicine will go to pediatrics.

Louis Kanda, Mutombo’s cousin (and Mimi’s husband) and a heart surgeon in Washington, D.C., designed the hospital and was responsible for all medical aspects, including hiring doctors and nurses. All of the hospital’s facilities are on one level, making for easier movement of patients.

Mutombo’s wife, Rose, also Congolese, sits on the foundation’s board. The four oldest of Mutombo’s children are adopted – Reagan, 22, Pearla, 21, Nancy, 20, and Harouna, 17 – and they volunteer at the foundation office in Atlanta. All have helped while the 7-foot-2 Mutombo, a four-time NBA defensive player of the year and an eight-time All-Star, continued his NBA career.

“He did an outstanding job” with the hospital while playing, said Rockets assistant coach Patrick Ewing, who is also an alum of Georgetown and will attend the ceremonial opening. “I’m sure it wasn’t easy. You can be focused on more than one thing.”

Mutombo also is a spokesman for CARE, the international relief agency, and the first Youth Emissary for the United Nations Development Program, which connects countries to knowledge and resources that help people build better lives.

Mutombo said he has been at the U.N. so much that it’s like “I work for them. They have my ID. They know everywhere I go.”