House for one a costly curiosity

SEATTLE – It’s an unlikely spot for a home.

There’s no grass in this south Seattle neighborhood, no sound of children playing. Instead, there’s a near-constant overhead rumble of cargo trucks on the Spokane Street Viaduct. The neighbors are foundries, cement silos, warehouses and rail cars.

Yet, every once in a while, a familiar suburban aroma, grilling meat, mingles with the industrial district’s usual tang of diesel exhaust and concrete dust. Those are the days when Joseph Aqui – behind 12-foot-high walls, a 1,700-pound magnetic door and watched by two security cameras – barbecues.

Welcome to King County’s $1.7 million “Secure Community Transition Facility,” a state-run halfway house designed to ease violent sex predators safely back into society.

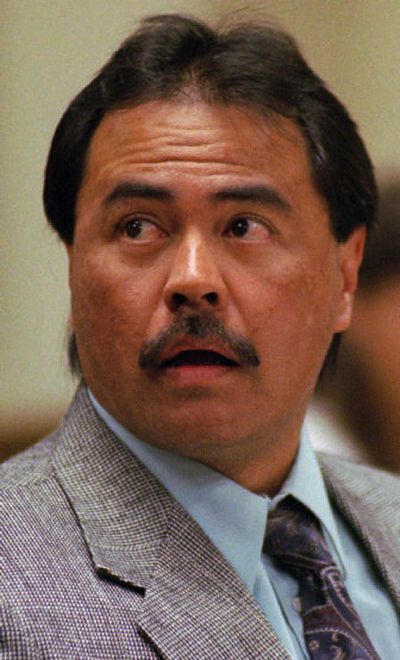

Aqui, a 53-year-old serial rapist, is the building’s lone resident.

Aqui arrived in February, after nearly 20 years in prison and about a decade more in the state’s controversial “civil commitment” program for sex predators deemed likely to rape again if released.

Aqui has admitted to 15 rapes and seven attempts. He typically raped women while burglarizing their homes in Walla Walla, Seattle, Bellevue and on the University of Puget Sound campus in Tacoma. He would cruise apartments, looking for women alone.

After years of holding such men in a secure “Special Commitment Center” adjacent to the state prison complex on McNeil Island, a federal judge in 1999 ordered the state to find a way for treated sex predators to graduate to less restrictive alternatives. A total of 238 sex predators are being held indefinitely in the civil confinement program.

Washington built a first halfway house, totaling 24 beds, on the prison island. But the court, threatening a $10 million fine, insisted on a second home on the mainland. The island halfway house “just wasn’t really a re-integration into the community,” said Allen Ziegler, administrator of the halfway house program for the state Department of Social and Health Services.

After a yearlong search, angry public meetings and rejection of several residential sites in Puget Sound, DSHS settled on the 1940s warehouse building in south Seattle. At the time, it contained a deli and real estate appraisal firm.

“There’s basically no vulnerable areas, no schools, nearby,” said Ziegler. “That doesn’t mean that the people working around this building were not very, very, very upset.”

In the end, the state signed a 10-year renewable lease and spent $1.7 million turning the warehouse into a window-less, earthquake-proof complex with 26 cameras, a backup generator, radio system and a tempered-glass surveillance booth overlooking the home’s central living room. A police officer sits in a cruiser parked outside.

The six-bed home has a $1.9 million budget next year, and approval for 17 staff members. (Twelve work there now.)

Depending on how one of the other sex predators progresses in treatment, Aqui might get a roommate later this year. But for now, the pricey living quarters are all his.

Stocks, and fly-tying

He jogs every morning on a treadmill and uses a stationary bicycle in the building’s central living room. There’s a large TV with satellite channels, some of them cut off to avoid arousing Aqui. A few potted plants dot the room.

He reads a lot. The living room tables are piled with Consumer Reports magazines, the Wall Street Journal, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seventh-day Adventist magazines, Forbes and a book titled “How to Clean Practically Anything.”

Aqui has declined repeated media requests for interviews.

But facility manager Tabitha Yockey said he particularly enjoys stock market research and tying fishing flies, which his wife sells.

Aqui attends a weekly counseling session with a sex offender treatment provider, as well as a weekly group meeting. He is allowed to leave the home – with a radio-toting escort in sight of him at all times – to go shopping, to restaurants, to the library and to look for work. He wears an electronic monitoring anklet at all times. And each time he leaves the home, staffers photograph him, so they can immediately describe his clothing to police if he flees. At night, staffers peer into his bedroom occasionally through a reinforced glass window in the door.

He’s trained as a baker, landscaper, sheet metal worker and data entry clerk, but so far, no one’s been willing to hire him. If they did, he’d have to be in view of a state escort at all times. By law, 15 percent of any earnings would go to the state as a token payment toward the costs of his confinement.

“Jobs are a bit of a challenge,” said Yockey.

‘It’s just crazy’

Even some of the most ardent backers of tougher sex-offender laws question the expense of the program.

“When you see this beautiful building – one guy, the cost, law enforcement, the TV cameras – it’s just crazy,” said Jim Hines, a Gig Harbor man who has pushed lawmakers for years to enact tougher penalties. “Nobody’s comfortable with these guys getting out, but even to me, this doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

Instead, Hines would like to see all Level 3 sex offenders – thousands of men – on electronic GPS monitoring and released into communities after they serve their sentences. The bracelets would tell monitoring officials where they are at all times.

“We owe it to our kids and communities to keep those most dangerous people on a short leash,” Hines said. “But to put them in a halfway house like this, I think, is silly. Does society feel safe that we’re spending $2 million on one guy? We could spend that $2 million on 50 or 1,000 or 200 guys who have equally scary backgrounds. I think it’s kind of a no-brainer.”

New, tougher laws

The number of civilly committed sex predators will likely start to shrink by the end of the decade, due to new state sentencing laws approved by the Legislature in 2000.

From 1983 through 2000, sex offenders received set sentences. Once the time was served, they walked out the door, unless the state considered them so dangerous that it tried to persuade a judge to civilly commit them as sex predators.

But in 2001, state lawmakers reverted to a parole-style system. Under this, sex criminals serve their sentence. But even after that there’s no guarantee that they’ll get out of prison. Instead, they petition periodically for release. If a person’s a threat, the state says no.

“On almost all sex offenses now, the state can continue to hold you for up to life in prison if you’re likely to sexually re-offend,” said Assistant Attorney General Todd Bowers.

And even with the tougher sentences, the state will likely continue to seek civil confinement for sex offenders who commit a “recent overt act” suggesting that they’re dangerous. In one recent King County case, for example, a sex offender was leaving explicit little notes on area playgrounds.

“Clearly, that’s a guy who’s deep into his offense cycle,” said Bowers.

A home without windows

Aqui’s planning a 4-foot by 4-foot vegetable garden in the concrete courtyard where he barbecues. His family – a wife he married while in prison and two children he fathered during conjugal visits – visit him sometimes in a conference room near the front entrance. Sometimes staffers will toss a football with him or play chess or Scrabble.

“When he first got here, he was kind of going stir-crazy,” said Yockey. There are no windows – the only natural light comes through a living room skylight high overhead and through “solar tubes” which direct sunlight from the roof into each resident’s small bedroom.

A small kitchen has a fryer, a rice cooker, blender, stove and refrigerator. A couple of cookbooks – “Cooking with 5 Ingredients” and “Low-fat Cooking for Dummies” – are perched on a shelf.

The exercise machines, cooking equipment and other amenities for residents are paid for by the state.

“It’s part of the institutional care program,” said Ziegler. “And we didn’t go out and buy the best of the best.”

Aqui’s requests are vetoed if the places are considered likely to trigger his sexual instincts. He wouldn’t be allowed to go to a park full of young women, for example. And although Safeco Field is just 10 blocks away, “we probably wouldn’t go to a ballgame,” Ziegler said. Aqui has asked to go see the new Superman movie, but the request won’t be approved until staffers look at reviews and check with people who’ve seen the film.

No one has ever confronted or even apparently recognized Aqui on his public trips to Fred Meyer, a local Asian grocery store or other places.

So far, 11 sex predators, including Aqui, have been placed in halfway houses or other community homes. Four live in the halfway house on McNeil Island. Three others share a home in Snohomish County. One, suffering from severe medical problems, is in an adult family home in King County. The other two are in Mason and Kitsap counties.

There are no immediate plans to build more halfway houses, Ziegler said. Between the one on McNeil Island and a potential six-bed expansion at the King County site, he said, the state can accommodate more than 30 transitioning sex predators before reaching capacity.