Lure of the ring

For Favio Medina, the path to boxing began in an alley behind an apartment complex in Anaheim, Calif. Curious about the rhythmic pummeling he was hearing, the 9-year-old followed the sound into a neighbor’s garage, where a man was punching a vinyl bag.

The skinny immigrant kid threw punches, too. In his mind, they landed with the skill and accuracy of blows delivered by Julio Cesar Chavez, one of the great Mexican boxers his dad watched on pay-per-view.

Favio and his younger brothers watched the fights as well, soaking up cultural pride.

“You watch all these Mexican fighters and it’s their heart,” Favio later said. “It’s like they’ve got something bigger to box for.”

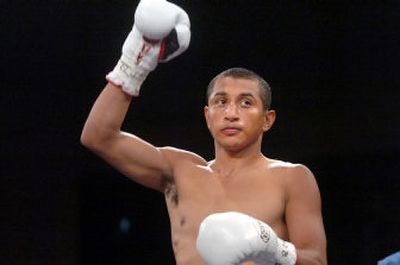

At the Coeur d’Alene Casino’s House of Fury last month the spotlight followed a wiry, dark-haired man into the ring. He removed a rosary from around his neck and crossed himself before facing his opponent. Fans in the crowd of 2,000 chanted “Fa-vi-o, Fa-vi-o.”

They had come to watch a Mexican boxer: him.

Boxing revival

The two fighters circle warily, feeling each other out. Favio, 25, is matched against 37-year-old Rudy Lovato of Gig Harbor, Wash., a gaunt-faced veteran of nearly 60 professional fights. Favio is fast and aggressive but has only fought professionally 13 times.

“When you fight Favio, you have to fight,” says Moe Smith, the House of Fury’s promoter. “He comes right at you like a bulldog.”

But Lovato is cagey, flicking quick, light jabs that keep Favio at arm’s length. He resists Favio’s efforts to back him onto the rope, where Favio typically scores with a flurry of punches. The crowd shifts restlessly at the defensive posturing, eager for more action. “Oh c’mon. What’s with the love taps?” one woman yells.

The bell rings, signaling the end of the first three-minute round. Favio’s trainer, Clint Anderson, gives earnest advice in the corner.

“You’ve got to get busier, Bud,” Anderson tells him. “You’ve got to let your hands go. …Work on cutting him off, don’t just chase him around the ring.”

Favio listens intently. Dreams are at stake. Last year, he was breathing Fiberglas dust at New Hampshire construction sites, his hopes for a boxing career fading.

At the urging of his future wife, Favio returned to Sandpoint, where he’d spent his high school years. He reconnected with Anderson, his former trainer, who drilled him on defense. Suddenly his career was on the upswing.

The casino’s House of Fury, the Inland Northwest’s largest live boxing venue, recently offered him a six-month contract to fight. Favio receives up to $3,000 for each fight, plus a monthly stipend and health insurance.

Tribal casinos are helping revive live boxing, offering venues outside Las Vegas and Atlantic City. They’ve become fertile ground for young fighters getting into the sport, says Jerry Armstrong, head of officials for the Idaho Boxing Commission.

But the odds of achieving fame are as brutal as a well-planted right hook. Fighters peak physically between age 25 and 30. The window of opportunity is short, and only a select few make it into big-money fights.

“There’s very little room at the top,” says the House of Fury’s Smith, whose own professional dreams were cut short by a detached retina.

Favio’s aspirations run high. “A world championship,” he says without hesitation. Julio Cesar Chavez won five world titles, and his 87 knockouts remain the stuff of boxing legend.

Smith, who promoted fights in Las Vegas and Reno, has spent 40 years assessing talent. Favio, he says, is still an unknown. “It takes about four years to find out what you’ve got,” Smith says.

Unlike some of the boxers he fights, Favio has no amateur background. He got his start in Tough Man contests at local bars. “He knew how to fight, but he didn’t know how to box,” Anderson says.

Since then, Favio’s gone on to win 10 professional fights, with two losses and a draw.

“Tough Mexican,” says Smith, summing up his latest fighter.

Favio and Lovato face off at the beginning of the second round, focused and intent. Tonight, two tough Mexicans are in the ring.

‘He took on anyone’

House of Fury fights draw an eclectic crowd. Friends and relatives of the boxers map out their own sections of the 2,000-seat arena. Others come to watch a good fight.

At the Worley casino, Smith’s efforts to develop local talent have increased the draw. The crowd chants the boxers’ names, as loyal as fans at a hometown football game.

“They’re from Sandpoint, Worley, St. Maries and Coeur d’Alene. We feel like we’re fighting, that’s what’s fun about it,” says Brad White, a friend of Anderson’s.

Favio was born in a small town near Guadalajara, Mexico, and spent his childhood in Southern California. But to the crowd, he’s a Sandpoint boy. After his dad, Bernie, got a job offer from a local ranch, Favio’s family landed in North Idaho. He was 13.

At Sandpoint High School, Favio signed up for small-scale bouts called “smoker fights,” winning every one. “Spar with me!” he begged bigger classmates.

“He was 120, 130 pounds. I was over 200,” says former schoolmate Matt Smith. “He took on anyone who’d fight him.”

Favio matured at 152 pounds. With a tapering torso and ropey muscles, he impressed Ashley Kearns, the girl he met on a construction site in 2002. Favio and his dad showed up to hang Sheetrock. They were startled to see two young women in hardhats working for their dad, the contractor.

“They were putting up trusses,” Favio says. “I told my dad, ‘One day, I’m going to marry a girl like that.’ “

Ashley, red-haired and normally outspoken, was suddenly shy. The 18-year-old begged her dad to sneak her into one of Favio’s fights at Coeur d’Alene’s Cotton Club.

A few months later, the House of Fury called Favio. A boxer had canceled. Would he fill in?

“It was his first professional fight. My sister and I spent so much time getting ready that we almost missed the first round,” Ashley says. When North Idaho’s construction industry cooled, Favio and his family moved to New Hampshire. Ashley went, too. The couple spent two difficult years in Tilton, a small New England town.

Favio worked at drywalling with his dad and two younger brothers, rushing off in the evenings to work out at the gym. He thought the populous East Coast would offer him more opportunities to fight, but he boxed professionally only three times. Injuries sidelined him.

Favio strained muscles lifting 200 pounds of Sheetrock over his head. He also developed a dry cough from breathing in the Fiberglas dust that seeped past his protective mask. Favio’s stamina started to slide. Aerobic conditioning is the basis of boxing, the foundation that sustains fighters during grueling rounds. His dreams of boxing were slipping away.

“I knew he had to get out of that job,” Ashley says. “It was killing him.”

They fought about whether he should quit. Favio didn’t know how they’d live without his $20 per hour earnings. “I’ll give up boxing,” he told Ashley.

“You’ll regret it,” she replied. “You’ll be an old man saying, ‘Oh, I could have been the best; I almost was.’ “They were still arguing when Ashley went home to Sandpoint to visit her family. She decided to stay and asked Favio to join her. They could live in an apartment above her dad’s garage. She would work, so Favio could train full time.

He moved back to Sandpoint and proposed.

Fight-card regulars

Round three ends. From the crowd’s perspective, it’s hard to tell who’s ahead. Favio is blocking most of Lovato’s punches, but Lovato is frustrating Favio’s efforts to score.

“Favio’s got the quicker hands, the stiffer punches,” Brad White says. Lovato’s experience, however, shows in his evasiveness.

In the corner, Anderson gives another “step it up” talk to Favio, whose breathing is still relaxed and easy, though rivulets of sweat run down his back.

Ashley is in the audience, sitting next to her dad. She’s Favio’s staunchest supporter, but matches are still hard on her. A punch can end a career, inflict permanent head injuries. Favio seldom dwells on that. Two black eyes and a twisted ankle during sparring are the worst he’s encountered.

For Favio’s parents, pride competes with trepidation on fight days. In Mexico, Maria Medina lights a candle for her oldest son. Bernie Medina prays. “Wear your rosary every day before you fight,” he tells Favio, who follows his advice.

Favio is also wearing new trunks for this match – a shimmering gray, classy but understated. Anderson and his son, Skyler, razzed Favio about them earlier in the evening. “They’ll be bad luck,” Anderson teased.

Ribbing is part of the landscape for the four boxers who appear regularly on the casino’s fight card. They train together at Anderson’s Newman Lake gym – a pole barn structure with a woodstove, a ring and a buzzer that marks three-minute rounds.

Rafael Cansino, 24, is a former high school football player who dropped 50 pounds to box.

Anderson’s son, Skyler, also competes. He’s 19, the youngest, and goes by the nickname “Baby Boy.”

Luke Munsen is the casino’s main event fighter. At 200 pounds, he’s a solid presence who takes blows like a shock absorber. Luke’s wife, Roxy, comes to practice once a week with the couple’s 3-year-old daughter and 18-month-old son. Their third child is due any day.

The evening’s card features five fights – Anderson’s four boxers plus an exhibition match. The local fighters are performing well. Rafael scored his first professional win.

Skyler knocked out his opponent in the second round. He’s working the crowd now – shaking hands, thanking people for coming, signing autographs. “You won’t be able to wipe a smile off his face for the next week,” Brad White says.

Skyler’s mom, Dawn, is grinning, too. “I get a great big old frying pan in my stomach when he fights,” she says, “but I’m fine now.”

Roxy, Luke’s wife, is sitting in the bleachers, hugely pregnant in a pink-and-white maternity smock. The couple is preparing for a home birth. After a bruising fight, Luke could speed home to deliver a baby.

The winner

Round four. Lovato’s mouth is hanging open, a sign he’s tiring. Favio is more confident, quicker to capitalize on his opponent’s mistakes – catching Lovato with his hands down, landing left hooks.

Boxers are like racehorses, Anderson says. Some are fast out of the gate; others start slowly, but finish in a sprint. Favio’s a slower starter. “It takes him about four rounds to warm up,” Anderson says.

The pressure of performing in front of a packed auditorium has faded. Favio’s less aware of the crowd, more focused on cutting off Lovato, pushing him back, crowding him.

“This guy isn’t as tough as I thought he was,” Favio told Anderson during the last break.

“You’ve been giving him too much respect,” Anderson replied. “Put the pressure on.”

Lovato is what Anderson calls an “old veteran.” From locker room chitchat before the fight, Lovato’s learned that Favio won’t stop punching. He’s trying to avoid those blows.

“He’s lost three times as many fights as Favio’s won,” Anderson says. “He’s been around the block.”

Smith, the House of Fury’s promoter, chose Lovato for Favio to fight with that in mind. Selecting boxing opponents is called “match-making.” Like a good marriage, an evenly matched bout will go the distance.

As the action picks up, the crowd resumes chanting “Fa-vi-o, Fa-vi-o.” Lovato still has a few tricks, grabbing and clutching at Favio – dirty defense intended to keep Favio from delivering powerful close-in blows.

At the end of eight rounds, however, an official lifts Favio’s arm high in the air, signaling victory. The crowd roars.

According to the scoring by three judges, Favio won seven of the eight rounds. “He took a lot of blows on the gloves,” one judge says.

Anderson thinks the match was actually closer. Favio is pensive. Lovato’s the kind of fighter who can make other boxers look bad winning.

The crowd’s attention has shifted to Luke, who is slugging it out with Tim Shocks, a theatrical fighter from Seattle.

‘People will know who he is’

Suddenly, the evening’s glitter is gone. The arena’s lights snap on, revealing a floor littered with discarded programs. The crowd is swarming the exits, and the clatter of cleanup crews has replaced the smooth baritone of the announcer.

Favio’s disappointment in his fight is palpable. Skyler, still euphoric from his knockout, grabs Favio in a bear hug and croons, “I love you, man.” Everyone laughs, the mood lightens.

Two kids hover at Favio’s elbow, waiting for autographs. Dawn Anderson is taking a head count of who’s coming over for a celebratory lasagna feed the next evening.

Favio draws a deep breath. His silver shorts are packed away; a baggy sweatshirt hides his boxer’s torso. He’s got hard work to do before his next fight in August.

Anderson will watch the fight video a half-dozen times, analyzing each move. He’s already decided that Favio needs to work on his straight right hand, an offense that could have shut down Lovato’s left jabs sooner. Favio will practice until the moves are instinctive.

Both men put their faith in the long hours Favio spends in the gym.

“Favio’s got a heart a mile long,” Anderson says. “In about two or three years from now, if he stays on the same course, people will know who he is.”