French minorities see parity in team’s mix

PARIS – In the French National Assembly, 11 of the 577 members are minorities. In French boardrooms, white men are the rule. But on the French national soccer team, 17 of the 23 players are minorities, and that gave the black and Arab populations here added cause for celebration when France beat Portugal last week to advance to today’s World Cup final match.

“I think the French team reflects the cultural diversity of France,” said Amely-James Koh-Bela, 42, who immigrated here from Cameroon in 1985 and has been seeking French citizenship ever since. “There’s nothing like it in the social, political or business fields. This is why I love the French team.”

France endured weeks of rioting last fall by minority youths protesting deep-seated discrimination and lack of opportunities, particularly in housing, employment and education. But when it comes to supporting the national soccer team, many minority members said they set hard feelings aside, because the team represents multiethnic France at its finest – even if it underscores the country’s failures in other areas.

“I like what they stand for, and I love France,” said Salah Zerouki, 38, who was born in France to Algerian parents. But, he said, “It’s racist to have the feeling that minorities can only make it in sports” and not in fields such as politics. “That showcases the reality of France – a mixed sports team but not mixed politics.”

The French national team had to confront the issue of its racial mix when the former French presidential candidate from the far-right National Front party, Jean-Marie Le Pen, told the daily sport newspaper L’Equipe that “perhaps the coach went overboard on the proportion of colored players.”

“The French don’t feel totally represented, which surely explains why the crowds are not as supportive as eight years ago,” when France won the World Cup, he said. The rallying cry of the ‘98 team was “black, blanc, beur” (black, white, Arab), to celebrate its broad racial mix.

“Hurrah for France – not the one he wants, the real one!” responded Lilian Thuram, 34, a black member of the national team from the French Caribbean island of Guadeloupe.

“Mr. Le Pen is not aware that there are black, blond and brown French people,” he told L’Equipe. “It’s like looking at the U.S. basketball team and being shocked that there are black people in the U.S.A.”

Following the riots last fall, French philosopher Alain Finkielkraut created controversy by telling Israel’s Haaretz newspaper that despite its earlier slogan, “the French national team is in fact black-black-black.” He added: “France is made fun of all around Europe because of that.”

“I think a lot of work remains to be done for this France called ‘black-white-Arab’ to be a reality, beyond the moments of national gathering like great soccer victories,” French government spokesman Jean-Francois Cope said last week on Radio J. “That is our goal.”

In France, it is illegal to collect data on race and ethnicity, and affirmative action is frowned upon.

According to unofficial estimates, about 10 percent of France’s 61 million residents are of Arab or African descent.

But few people dispute that discrimination is rampant across society – French-born children of immigrants suffer unemployment rates as high as 40 percent, double those of whites – and that was one reason why many said they took special pride in the French team.

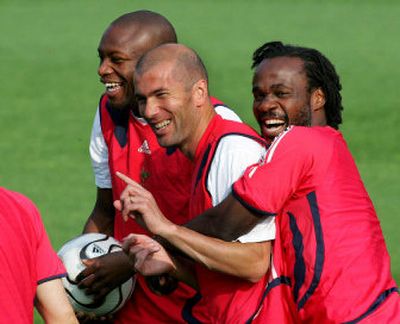

Koceila Bouhanik, 21, a French student from north of Paris whose parents came from Algeria, noted the large number of minorities on the team “who speak and think like me” – including the captain, Zinedine Zidane, also of Algerian descent. He called the team “a model of integration and success.”

But Nicolas Bonachera, 21, a semi-employed white man from western Paris, doubted what practical influence the team can have.

“This team has the power to make a nation dream of diversity and success, but I think it’s an illusion,” he said. “I can’t believe that everybody feels united over soccer, whereas nobody is (united) on other issues the rest of the year.”

“The French football team shows the mix and the diversity of French society as a whole, but it doesn’t represent what is occurring in French society today,” said Dogad Dogoui, 42, president of Africagora, a group that promotes racial integration and diversity.

Especially in business and political spheres, he said, “Power is in the hands of a small ruling minority that doesn’t represent France as a whole. A real cultural revolution has to occur here for the situation to change.”