‘Green’ houses get cold, hard cash

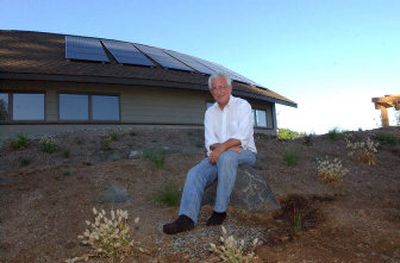

For a family with five cars, an artificial waterfall and a 2,400-square-foot hilltop home, the Garsts have a surprisingly small environmental footprint.

Their vehicles – including a large camper van – average 42 miles a gallon. Their home is a model of high-efficiency construction. And even in often-rainy Olympia, about two-thirds of their power comes from a $27,000 array of solar cells bolted to the roof.

Now the Garsts and more than 100 other Washingtonians are about to get a little of their investment back. Under a new law, alternative power producers who sign up with the state can get up to $2,000 a year in payments from their local electric utilities.

These aren’t payments for selling power to the utility. The checks are delivered even if a family – as the Garsts do – uses every watt of power they produce.

“All you have to do is produce,” said Mark Bohe, a tax policy specialist with the state Department of Revenue.

The signup deadline is nearing for the first year’s payment, which covers power produced from July 1, 2005, through June 2006. The one-page forms for state certification are at www.dor.wa.gov. A second form goes to participating utility companies. The deadline for a state certification request is July 31, although the agency may extend that a couple of months.

In Cheney, John and Bonnie Mager have already signed up for the state program. They have a small $8,000 solar system: a dozen panels atop the roof of their barn.

“It’s more psychological than financial,” said John Mager. “It was kind of the right thing to do.”

State lawmakers, led by the political odd-couple team of conservative Sen. Bob Morton, R-Orient, and liberal Sen. Eric Poulsen, D-Seattle, approved the alternative-power program last year. The goal was twofold: to spur in-state manufacturing jobs while decreasing the need for more power plants. The program lasts through the summer of 2014.

Washington is home to several major alternative energy companies. Moses Lake’s fast-expanding REC Silicon plant is now the largest producer of solar-grade silicon in the world, according to Mike Nelson, who runs Washington State University’s Northwest Solar Center. Two companies in Arlington and one in Bellingham make inverters, which convert solar cells’ DC current to the AC used in homes.

The new law gives utility companies tax credits in exchange for paying people who install wind-, solar- or manure-to-methane setups that produce electricity. Applicants can be individuals, businesses or local governments. The amount is also based on how much power a system produces, with bonus points for system components made in Washington.

“It’s not 100 percent payback yet, but it makes it feasible for people in the middle class,” said Bohe. “The whole goal is to have thousands – maybe hundreds of thousands – of cottage-industry systems generating energy.”

Most of the certified systems so far are in Western Washington, where the climate demands an extra 15 percent of the panels to get the same power as in sunnier Eastern Washington.

“We wanted to see if it would work,” said David Purtee, a retired state worker who installed a $16,000 solar system on his roof in Olympia. “People in the Northwest kind of pooh-pooh it and say this is a foggy place. They’re right, yet we’re able to generate 20 to 25 percent of our power.”

Still, as the neighbors’ trees grow and shade their panels, he and his wife Karen joke about midnight timber harvests. In reality, Purtee said, they hope to eventually move to 20 acres they own on a hillside near Moscow, Idaho. They’ll take their solar panels with them. Purtee said it’s also an ideal site for wind power.

An average home solar system using Washington-made inverters and panels costs $28,000 to $35,000, according to the Department of Revenue. The state payments for such a system would total $18,000 over nine years. A federal income tax credit, local power company incentives and Bonneville Environmental Foundation payments can shave thousands of dollars more off the cost. Plus, the electric bill – when there is one – is much lower.

“It’s a hell of a deal,” said Garst, a retired businessman and former federal energy official.

It’s a deal – at least the state part of it – that relatively few people know about. Nelson, who approves the certification requests for the state, said that about 130 systems have been certified, almost all of them homeowners.

Among them is Garst, who’s taken his green home far beyond what most applicants do. A heat pump draws heat from the ground. Rainwater collects in a massive cistern behind his home. A solar array powers a 10-foot sunup-to-sundown waterfall beside his home, next to a tiny private sand beach.

The kitchen floor is made of recycled tires. The landscaping includes “rain gardens” to catch runoff and drain it down through crushed glass and crumbled concrete. And the driveway is made of a special “pervious concrete,” to avoid runoff. Closet lights are connected to motion detectors, so no one accidentally leaves them on. A special exchanger captures the heat in air exhausted from the home.

And even in Olympia, where clouds and rain dominate the forecast for months each year, there are some additional perks to a home designed with the sun in mind. A sunroom serves as a greenhouse, where heat-loving cucumbers and peppers grow atop water-filled barrels. The barrels capture daytime heat for cool evenings.

“I’ve got an orange tree on order,” Garst said. He’s thinking about grapefruit and banana trees as well.