War correspondents despair as Americans tune out

News of the bombing that felled a CBS news crew washed over Baghdad’s tight-knit media corps like a tempest this week – evoking waves of anxiety, sadness, resolve and more than a little dismay.

American television journalists covering Iraq confronted the difficult irony that it took the deaths of a cameraman and soundman and critical injuries to correspondent Kimberly Dozier to help push the story of Iraq back to the forefront of the nightly news back home.

The amount of time devoted to Iraq on the three television networks’ weeknight newscasts has dropped by nearly 60 percent from 2003 to the first four months of 2006, according to the independent Tyndall Report tracking service.

Even before Monday’s attack, some network television correspondents had reached the unsettling conclusion that audiences and producers had grown weary of much of the war coverage.

ABC correspondent John Berman in Baghdad wrote in his blog recently that he and his colleagues felt like the castaways on the network’s prime-time drama “Lost” – “We have come to the conclusion that no one knows we are here.”

One NBC veteran expressed frustration at the current verities of the nightly news – the demand for ever-more-vivid storytelling to help combat audience “fatigue.”

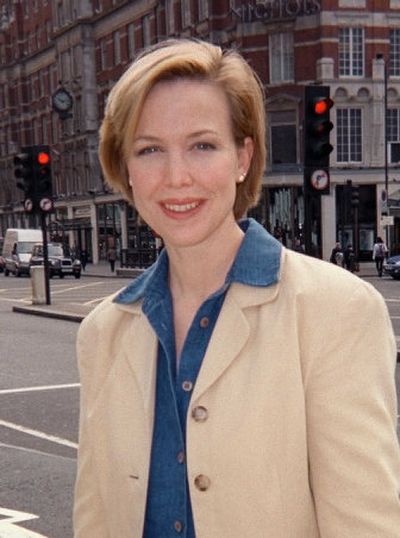

“I think we are all very concerned that the war and Iraq are not getting their due,” said Allen Pizzey of CBS, who recently rotated out of Baghdad to London. “You think, ‘What the hell are we out there for?’ “

NBC News President Steve Capus said the network’s coverage was “extensive,” giving “an accurate depiction of what’s going on over there.”

Coverage of Iraq has also been a political issue, with President Bush and his top aides accusing the media of driving down public support for the war by reporting only the “bad news.”

Yet media critics from differing points on the ideological spectrum voice similar complaints about the decline in the number of stories.

“The idea that the Brangelina baby or some salacious trial might trump coverage of the war is just stunning to me,” said Cori Dauber, a University of North Carolina researcher who has criticized television coverage from Iraq.

Sean Aday, an assistant professor in media and public affairs at George Washington University, reviewed all of the nightly news for NBC and Fox News in 2005 and found that they did not report most U.S. military deaths. Both news outlets also covered an even smaller fraction of violence against Iraqis, he found.

Aday attributed what he called the under-reporting to multiple factors, including the danger faced by journalists reporting the story; that random violence typically occurs outside a camera’s view; the sense among news executives that continuing attacks are no longer “news”; and, finally, political pressure on the networks.

Aday said that the constant attacks on the media for alleged negative coverage “have got to be in the back of their heads when they make these decisions.”

Many journalists who have covered multiple wars around the world agreed that Iraq was their most dangerous assignment. Nearly 100 journalists and their support personnel – the majority of them Iraqis – have died since the U.S.-led invasion in 2003, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Correspondents for all the networks still routinely conduct interviews across Baghdad and the rest of the country. But most try to limit these to well under an hour. “Man on the street” interviews are considered virtually impossible.

Employing such hit-and-run tactics means stories take longer to complete, said NBC correspondent Jim Maceda, who described the long hours and repeated visits it took him and his crew to complete a feature on the Baghdad symphony. “All of the conditions militate against getting the story,” Maceda said.

Still, he and other TV reporters have watched in frustration as stories they do complete from Iraq fail to make the air, or are delayed.

“I think there is a sense among the (producers) that viewers are turned off by stories from Iraq,” said Berman, “so the bar is very high to get stories from there on the air and getting higher all the time.”