Haunted dreams

DENVER — A few years ago, Lynton Harris sank $2 million into a Washington, D.C., haunted house that included a room themed “Escape From the Pentagon.”

Two weeks before opening night, terrorists attacked the Pentagon and the World Trade Center. The room was suddenly out of place, and no one was in a mood to hear the words “terror” and “terrifying.” The entire 65,000-square-foot Extreme Scream Park was scrapped. Harris’ Sudden Impact Entertainment Co. took a financial beating. He tried again the next year, and a wave of sniper shootings around Washington crushed him again.

In the business of haunted attractions, it isn’t just the visitors who have to expect the unexpected.

Three decades after the haunted house industry established itself, the business is seeing some dramatic changes. The charity haunts pioneered by the Jaycees and other groups with homemade effects are out. For-profit, big-budget haunts stocked with digital effects and animatronics are in. And as promoters cater to a generation that grew up with ultra-realistic video games and films, they are drawing electronics firms and engineers into what once was a niche industry.

Leonard Pickel, publisher of Haunted Attraction magazine, estimates haunted houses nationwide generate $300 million every year, not including permanent attractions at tourist destinations or haunted nights at big amusement parks such as Busch Gardens, Universal Studios and Knott’s Berry Farm.

For a professional haunt, even small operators can spend more than $100,000. They can also lose that much. But the rewards, too, can be significant, with as many as 15,000 people filing through in a season, paying on average $10 to $13 each.

“Somebody drives by a house on Halloween night and sees a line wrapped around the building, he multiplies that by ticket prices and how many days there are in October, and he thinks this guy’s making a fortune,” Pickel said. “You have know what you’re doing or you’re going to get burned.

“People ask me how much it costs to run a haunted house. I tell them every penny that you can lay your hands on, and then some.”

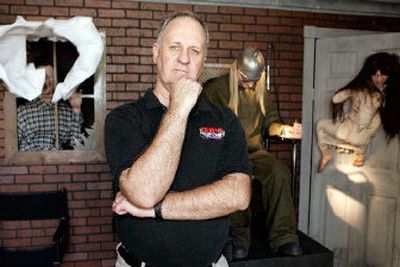

Pickel was one of the hosts at last month’s Hauntcon convention in Denver, along with a list of sponsors that included computerized ticketing systems, a hearse owners club and Internet-based haunted house suppliers.

Conventions are a way for niche companies to find buyers. Pickel said gatherings like his give buyers a hands-on peek at new products, everything from the latest in advertising techniques and Web design to makeup, computer-generated portraits with eyes that follow visitors around the room (only $60 each) and companies such as Distortions, which offers a foam-rubber autopsied body (billed as “disturbing, but in good taste”).

Pickel said he aims to help some of the nation’s 3,000 to 5,000 haunted houses turn a profit in a deceptively risky business. He estimates 40 percent fail in their first year. But through seminars and just sharing stories, newcomers can learn how to save money and create a quality attraction.

Real estate has become a big factor. Rising property values have meant fewer vacant buildings, and fewer landlords will lease a large building for just 30 days. Harris said the lessons of 2001 and 2002 made him stop depending on Halloween, and drove his company into year-round haunted ventures that can sustain the occasional bump.

The difficulties don’t stop newcomers from trying, keeping the number of haunts relatively steady from year to year. The details, however, have changed. Forget bedsheet ghosts, peeled-grape “eyeballs” and cold spaghetti “intestines” — haunters want the latest in 21st century things that go bump in the night.

“What’s happening here is we’re bringing Disney down to the home level,” said Robert Van Deest, an engineer at Blue Point Engineering Inc., a Longmont-based robotics company that uses computers to synchronize sound, light and movement.