Demons no match for Tapia

Johnny Tapia, by his own count, has died six times.

That didn’t count the time he wanted to die but couldn’t pull the trigger of the pistol he had stuck in his mouth fast enough. When that didn’t work, he ran into the kitchen, grabbed a knife and stabbed himself.

Funny, because Tapia always did things fast. In the ring he threw punches nonstop from every angle. Outside it, he was just as quick to take solace with a drug or a bottle.

He fought with fury, and lived his life just as furiously.

“I had a power plant inside me. I was lit up all day long like a nuclear reactor,” Tapia said. “Don’t nobody know where that comes from. And ain’t nobody known how to turn it off.”

He nearly drowned one day while trying to swim the Rio Grande on a bet even though he couldn’t swim. Five other times, doctors had to bring him back from the dead after various overdoses.

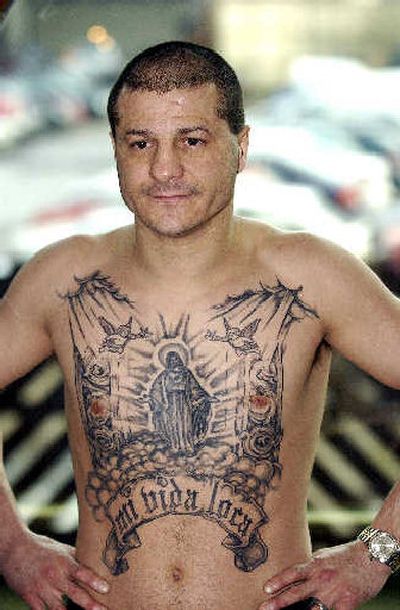

The craziest thing about “Mi Vida Loca” is that Tapia is still around to tell about it at all. Even crazier is that he has written a book of that title with the hope it might save others.

“God works in mysterious ways,” Tapia said. “I’m a big believer in that.”

The fact that Tapia is alive, reasonably coherent, and around to believe after years of boozing, bingeing and taking thousands of punches to the head is a miracle by itself.

This, however, isn’t the classic boxer gone bad story. This runs far deeper.

Back to when Tapia was a little boy in Albuquerque, N.M., who idolized his mother. Back to the night she never returned from a date. Back to the next day when she was found with 26 stab wounds from a screwdriver, another seven from a pair of scissors.

Tapia has been fighting for 19 years as a pro, 30 years all together.

He’s fought the demons inside even longer.

He kept winning fights because he fought with a fury no 115-pound man should have. He fought for his mother, looking at the face of every man across him in the ring as if he might have been the one who got away with her murder.

Tapia remembers his mother, Virginia, as the most beautiful woman he could imagine. He remembers living with her and their dog, Whiskey, in a little house in the barrio with the Christmas lights up on the roof all year.

Her death shattered him, destroyed his life. Tapia lived with his grandparents and 15 uncles and cousins, sleeping at night on the porch floor. Breakfast was most often a piece of white bread with mustard on it. On a good day there might be some Dr Pepper in a cup.

You didn’t complain or you got a beating. Tapia got lots of beatings, but there was something different about this boy. He didn’t mind getting hit, and soon he was taking on bigger kids and giving beatings himself.

At 9 years old, his uncles would take him to street corners or back alleys to fight bigger guys. If he won, he would get a dollar. If he lost, he would get a beating from an uncle.

“Pretty soon I’m not losing any more,” Tapia wrote. “It wasn’t worth losing.”

He became an amateur fighter two years later, a 56-pounder who put rocks in his pockets so he would weigh the minimum 70 pounds to fight. Tapia overwhelmed opponents, but life was often overwhelming itself.

His pro career had just begun when he discovered cocaine.

He fell in love with it. It made him numb, made him forget the demons.

On his wedding night, his new bride got a call from the hospital that her husband had overdosed and might not make it. Teresa Tapia, who would become his manager and his strength, got a lot of calls like that.

The only other outlet for Tapia was the ring. He was relentless, staying undefeated for 11 years and winning titles five times.

When the fight was over, though, the darkness returned. Tapia binged on drugs and alcohol, not caring if he lived or died.

He felt responsible for his mother’s death, was tormented by the fact her killer had never been found. But when police reopened the old investigation and found out how she was killed and who killed her, the pain got worse.

The man police identified as his mother’s killer had been run over and killed six months earlier.

Tapia felt cheated once more.

“I wish I could have gotten him, but I wouldn’t be at the place I am now if I did,” he said.

That place is clean and sober and ready to fight again. Tapia finally hit bottom after one last suicide attempt left him in a coma for 36 hours in a Las Vegas hospital and he spent six weeks in a rehab center.

The book bares all – or almost all. Tapia said he left out some of the darker parts because they were so bad no one would want to read it.

He said he’s taking one day at a time, and on this day he was speaking to young inmates in Philadelphia telling them his story. At age 39 his best days are behind him, but he plans to fight two more times before calling it a career.

The demons still haunt him, and he can’t guarantee they won’t overwhelm him again. For now he has them under control.

“Mi Vida Loca” is never far away.

“I’m able to find some peace with myself,” Tapia said. “And if I can help somebody else, it’s a blessing for me.”