Nothing is getting lost in translation

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — The past few years have shown that U.S. government intelligence goes only so far. One of the biggest challenges is recognizing vital information in foreign languages — and acting quickly on it.

That’s why the military would love software that can listen to TV broadcasts or phone conversations and read Web sites in Arabic and Chinese, translate them into English and summarize the key elements for humans.

But each of those steps has long bedeviled computer scientists. Perfecting them and combining them — well, that is “DARPA hard.” That means it’s difficult even by the extreme standards of the Pentagon’s next-generation technology arm, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Last year DARPA launched a project that aims to create that real-time translation software. It’s called GALE, for Global Autonomous Language Exploitation. And on top of GALE’s technical challenges, DARPA added some twists.

It hired three teams of researchers to chase the problem for up to five years. Each year, their progress would be evaluated, and the worst-performing team could be eliminated. Or the program could be shut down entirely.

DARPA often threatens to cut — “downselect” in its lingo — people from a project. But in the small world of speech-to-text and machine-translation researchers, being booted off the GALE island would be an unfamiliar blow.

That’s because DARPA’s three choices for GALE contestants were among the best of the best: IBM Corp., backed by a $6 billion annual research budget; SRI International, a $300 million, nonprofit research organization based in Silicon Valley; and BBN Technologies Inc., a $200 million research contractor headquartered in Cambridge.

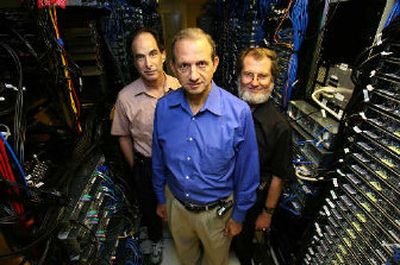

Being ejected would be “unthinkable,” said John Makhoul, the head of BBN’s GALE team.

“I cannot entertain that idea right now,” he said several months before DARPA’s first evaluation.

A display in the lobby boasts that BBN is “where wizards work.” The company — formerly called Bolt, Beranek and Newman, its founders — might best be known for its seminal 1960s work on the computer network that became the Internet.

But the company also is a longtime hub for speech-recognition and translation technologies.

Even with all this expertise, BBN, SRI and IBM needed help. In a frenzy of phone calls and e-mails shortly after GALE was announced, representatives from each site raced to line up subcontractors at top university labs around the world.

“This is a little like the making of sausage,” said David Israel, who headed SRI’s team.

In fact, for all of GALE’s linguistic complexity, it might have paled next to what each team faced merely in combining the work done by the outside people brought aboard.

“We’ve never had a project of this complexity,” BBN researcher Owen Kimball said in April. “You’re going to see people ripping their hair out.”

The GALE evaluation was still months off, but the team — heavily made up of immigrant engineers who had undertaken their own personal language projects in coming to America — was hunkering down.

“Put it this way: You can get your e-mail answered right away at 3 a.m. — by a lot of people,” said computer scientist Long Nguyen.

GALE’s goal is to deliver, by 2010, software that can almost instantly translate Arabic and Mandarin Chinese with 90 to 95 percent accuracy.

That might be impossible. Humans might not even be that precise. Consider all the ways we mishear each other, or fail to grasp idioms, or apply one subjective interpretation instead of another.

Fortunately for the GALE teams, they didn’t have to be near 95 percent right away. In the first year, they were expected to translate Arabic and Mandarin speech with 65 percent accuracy; with text the goal was 75 percent.

How hard was that? Before GALE, DARPA estimated that the best systems could translate foreign news stories at 55 percent accuracy.

To wring improvements from their translation software, the GALE teams fed their computers huge pools of sample broadcasts and texts in Arabic and Chinese. As the machines were exposed to more and more foreign sentences, they analyzed the content and structure, compiling an ever-deeper library of how words are spoken and the rules governing the languages.

The defining element of GALE — the government’s evaluation — was on the honor system. The teams got the test in June — hours of audio and dozens of documents in Arabic and Mandarin — and were expected to turn in their results later.

DARPA judges scored the computer translations by counting the number of human edits that the sentences needed in order for them to have the correct meaning. By this measure, the results largely met DARPA’s demands of 75 percent accuracy for text translation and 65 percent for speech.

But it was not until three months later — after all three teams began working on year two of GALE in case they were picked to continue — that the researchers got DARPA’s ruling about who passed.

So who got rejected? No one.

At least not yet.

DARPA Director Anthony Tether and GALE program manager Joseph Olive decided each team had shown significant progress worth continuing to track.

But they did tighten the screws. In addition to expecting better translation accuracy in each of GALE’s four remaining years, DARPA will measure that performance more stringently.