Chinatown headline San Francisco’s Chinatown

SAN FRANCISCO – It’s Chinatown. You’ve been there and done that, strolling vaguely under the dragon gate at Grant Avenue, dawdling past the kitschy gift shops, then strolling out again – maybe not much wiser, maybe not much merrier.

But this, it turns out, was our own fault. Last month, for reasons that will become clear and for the first time in 30 years of visits to San Francisco, I gave this Chinatown some serious time and attention.

In 48 hours, I left only once, for a 10-minute cable-car ride. In return, Chinatown delivered joy, intrigue, retail temptation, good cheap food and a bracing glimpse into harsh history and contemporary poverty, all in the space of about 24 blocks.

Yes, the storefronts along the first few blocks of the main drag were peddling enough T-shirts, key chains and tchotchkes to bury again the terra-cotta warriors of Xian.

But here’s the solution: You walk a little farther. You sip some premium tea, browse the kite shop, gorge on dim sum.

Or swallow a little pride and sign on for a tour with somebody who knows the neighborhood – preferably somebody who speaks Cantonese, the area’s dominant dialect.

You’re apt to learn where to buy live frogs for $2.99 a pound (Luen Fat Market, 1135 Stockton St.) or discover what waits at the top of the fragrant four-story stairwell at 125 Waverly Place. (It’s the Tien Hau Temple, one of the oldest Chinese temples in North America, its tiny space cloudy with incense, its balcony altar eerily aligned with the spire of the Transamerica pyramid.)

There is, however, a risk to this approach: Much of what you thought you knew about Chinatown may be destroyed.

That atmospheric entrance gate above Grant Avenue, for instance. That always looked to me like a handsome relic from years gone by. Turns out it went up in 1970, about 120 years after the community began taking shape. Most of the 900 buildings in Chinatown are older than that gate.

In leaving behind the violence and hunger of China’s Guangdong Province in the 1850s to join in the California Gold Rush, the first Chinese immigrants here found themselves deterred from mining because of steep taxes on foreigners and barred from many other businesses by less formal means.

Those who didn’t end up working on the railroad often took on other jobs that white men weren’t interested in: running laundries, for instance, and restaurants.

By 1870, the streets around Portsmouth Square were full of Chinese businesses. And by 1905, despite widespread prejudice and federal laws forbidding the arrival of new Chinese laborers and blocking these immigrants from naturalized citizenship, a strange but lively community had bloomed.

Its population was mostly male, its margins occupied by opium dens, gambling parlors and brothels whose customers often were from outside the neighborhood.

Then came the quake and fires of 1906, which leveled the place, and a proposal by San Francisco’s movers and shakers to take over the valuable real estate of Chinatown and move the Chinese elsewhere.

But it didn’t happen that way. Instead, the Chinese family associations that ran the community – you can still see their fancy balconies overlooking Waverly Place – raced to rebuild the district to double as a tourist attraction. Up went tile roofs and street lanterns, curving eaves and stylized facades.

Thus, by the time I showed up with my wife, Mary Frances, and our daughter, Grace Li Qi, the neighborhood had spent two-thirds of its history living a double life as a crash pad for immigrants and a stage set for tourists.

In my house, we’re in the early stages of learning how to be an Asian American family. Grace Li Qi, who will be 3 in May, was born in the Sichuan province and came home with us in July 2005. The more Chinese history we can find and touch, the better.

We wandered amid the 21-string “guzhengs” and two-string “erhus” of the Clarion Music Center on Sacramento Street, where the clerk tutored Grace in drum technique. We dined at the House of Nanking, where the waitress demanded a kiss from her.

We checked out the bricks of Old St. Mary’s on California Street, the first cathedral in California, and browsed a contemporary art show at the Chinese Culture Center in our hotel, the Hilton on Kearny Street.

“What we have in Chinatown is the beginnings of the Chinese presence in America,” said the Rev. Norman Fong, deputy director of the nonprofit Chinatown Community Development Center. “So we have all the ‘oldests’ – the oldest Chinese Christian church. The oldest Buddhist temples. The oldest family associations. The oldest alleyways and streets.”

Looking to promote straight talk about history, create a few jobs and tidy up the neighborhood, Fong’s agency in 2002 created Chinatown Alleyway Tours, in which teens and twentysomethings from Chinatown give visitors an insider’s perspective.

Other agencies, too, are eager to take visitors deeper into the community. We signed on for a three-hour neighborhood tour by Wok Wiz Chinatown Walking Tours, a side venture of celebrity chef Shirley Fong-Torres, who handed us over to guide Lola Hom, who grew up in the area.

We stopped at the last fortune-cookie factory in Chinatown, a dim, cluttered space at 56 Ross Alley in which a pair of weary women stamped and stuffed cookies next to a sign that urged a 50-cent tip from anyone planning to use a camera.

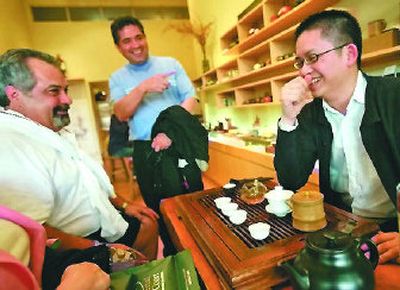

Hom led us inside 831 Grant, the longtime home of an apothecary and tea shop formerly known as Yau Hing Co.

For years, this family business’ display area featured ‘70s paneling, linoleum floors and tea canisters labeled only in Chinese. Then about five years ago, siblings Peter and Alice Luong stepped up and decided to focus the storefront on one specialty – tea – with a contemporary presentation.

Now the sign in front says Red Blossom Tea Co., and the space is all blond wood, muted hues and sleek teapots.

With ambitious Asian families supplying University of California, Berkeley, with 40 percent of its undergraduates, it’s reasonable for an outsider to wonder: How many Chinese still live in Chinatown?

The answer is a lot, because this remains a first stop for new immigrants and a haven for holdovers. In the roughly 24 square blocks that make up Chinatown’s core, 22,000 to 30,000 people reside (depending on who’s estimating), most of them Cantonese-speaking Chinese, many in one-room apartments or government-subsidized public housing.

Chinatown remains among the poorest and least-educated neighborhoods in San Francisco – a “gilded ghetto,” in one author’s phrase.

“Most of our people here, in the core of Chinatown, live below the poverty line,” said Rose Pak, general consultant to the Chinese Chamber of Commerce in San Francisco. “This will always be a haven and orientation point for newcomers, because of the language and the availability of social services.”

Certainly, the neighborhood’s celebrations are more spectacular than its troubles. First there’s the two-week spring festival that culminates with the lunar new year parade, an epic night of marching and fireworks that typically takes place under cold, rainy skies in late February or early March.

In September comes the Autumn Moon Festival, which features hourly lion dances, drummers, martial arts demonstrations and moon cakes with bean-paste fillings.

Still, once you’ve been briefed, it’s certainly easy enough to see workaday Chinatown.

At First Incense Corp., 753 Jackson St., you can check out the symbolic paper models that mourners burn as a gesture to provide comforts for loved ones in the next life.

Would the departed enjoy a Mercedes? Fifty-five dollars. A pair of servants in red and green outfits? Sixty-eight dollars. (And if you come upon a creeping hearse and marching brass band here, you’re not having a New Orleans hallucination. It’s a Chinatown funeral tradition that goes back a century.)

The second-best public place to see unvarnished Chinatown may be Portsmouth Square. This was the center of San Francisco immigrant civilization when the first Chinese arrived, and it remains busy.

“This is their living room,” Hom told us.

Those thousands of Chinatown residents of single-room abodes that share bathrooms and kitchens come here by day to chat, smoke and play cards or Chinese chess. Especially the seniors. And I have to say, they made me feel about as welcome as I’d make them feel if they showed up uninvited in my living room.

We felt far more comfortable – and found seats – a few blocks away in the Willie “Woo Woo” Wong Playground on Sacramento Street near Grant, a public space that dates to the 1920s. For decades, it was known simply as the Chinese playground, and it incubated neighborhood legends like that of Willie Wong, a basketball star in high school and college despite standing just 5 feet, 5 inches. He died at age 79 in 2005. Soon afterward, Chinatown leaders persuaded the city to rename the park for him.

The highlight of our visit came on the sidewalk outside the Hilton on Kearny Street.

This was the second night of our stay, an unusually warm and dry Saturday night, and as luck would have it, the night of the Chinese New Year Parade. Welcome, Year of the Boar. (Or pig, depending on your preference.)

All day long, the three of us had pounded Chinatown’s pavement, looking, sniffing and listening. Now, as we stood on the curb, Chinese San Francisco washed over us, the dancers and drummers fortified by marching bands, the bands followed by beauty queens, the beauty queens chased by Board of Equalization officials, the Board of Equalization officials trailed by dragons.

And these were not small dragons. The longest measured 201 feet, with about 100 feet of men and women inside from Leung’s White Crane dance and martial arts school.

Drawing upon more than two millenniums of tradition, it writhed wildly enough to fill every lane of Kearny Street, its many-colored flanks lighted from within like the granddaddy of all glow worms.

When it lurched our way, as immense and wonderful as anything Grace had ever seen, she had to reach out and touch it, and we were happy to help.