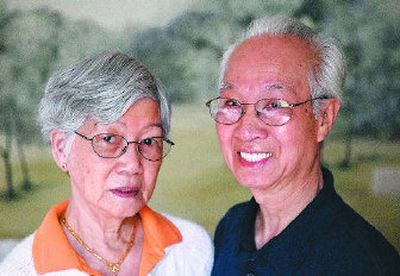

Arranged marriage thrives 57 years

Eddy Eng saw his future bride for the first time, across a crowded marketplace in a small village 90 miles southwest of Hong Kong.

The next day they were engaged.

Eng’s grandfather, and later his father, had immigrated to the United States as young men. In those days only men and children could immigrate. Women were not allowed.

Eng joined his father in Seattle when he was 9 years old, leaving his mother behind.

In 1947 his grandfather returned to China with Eng and his brother.

“He wanted us to learn our Chinese language and to read and write it fluently,” Eng recalled. They lived with Eng’s mother in Hong Kong.

When he was 19, his mother took him to their village to meet a wife. No one asked him if he wanted one.

“We didn’t have independent minds,” Eng said. “My mom said we’re going to the village to get a wife, so I went.”

Cynthia, his future bride, came to the market with her parents. She stood across from him and didn’t say a word. Eng arrived, accompanied by his mother.

“We didn’t get to visit,” he said. “We just stood and looked at each other. After that, the parents agreed we’d marry.

“The next day the parents had a luncheon, and I gave Cynthia a ring my mom had given me for her.”

Fifty-seven years later, his shy wife still has little to say. When asked what she thought the first time she saw Eddy, she shook her head and smiled.

“I was too young,” she said. “I didn’t know what to think.”

In China, this was simply the way things were done. Young people did what their parents told them to do, without question

On Jan. 29, 1950, three months after they first glimpsed each other, they were married. The black and white wedding photo of the 19-year-old groom and his 17-year-old bride reveals an incredibly youthful couple.

In his North Side living room, Eng fondly caressed the photo.

“She’s my little doll,” he said.

For two years the newlyweds shared a three-bedroom flat in Hong Kong with his mother and his younger brother and sister-in-law.

At the time of their engagement, all the family’s land in the nearby village had been taken over by the communists.

“We had no home to go back to,” Eng said.

The immigration laws had recently changed to allow women to accompany their husbands to the United States.

“I decided on my own to bring my wife to the States,” Eng recalled. “It was the first decision I ever made in my life.” He was 21 years old.

He paused, ooked across the table at his wife, and said: “I think I made the right decision.”

The Engs docked in San Francisco on Jan. 6, 1952. The next day, Cynthia delivered their first child, a son they named Dennis.

A few days later they flew to Seattle, and three months after that they joined Eng’s father, Tom, in Spokane. Tom Eng had opened the Cathay Inn on Division Street in 1950.

Eddy joined him at the restaurant, taking over in 1960.

The Engs added three more children to their family and raised them all on the North Side.

“Cynthia stayed home with the kids,” Eddy said. “We never hired a baby sitter in our lives.”

Eng worked hard at the thriving restaurant, often working 12 to 14 hours a day.

“I never stopped,” he said.

When asked if she wished her husband had been home more when the children were young, Cynthia seemed surprised by the question. She ducked her head shyly.

“I don’t know,” she murmured through her smile.

At the grand reopening celebration of the Cathay Inn in 1998, Eng acknowledged his wife. He said to the assembled crowd, “Most of all I thank Cynthia for keeping the home fires burning,” he said, growing tearful at the memory. “Without the home fires burning, what’s the point of all the hard work?”

Noting the huge differences in culture and tradition between East and West, Eng said, “I think people grow up too fast here.”

He feels luckier than his sons because he had the benefit of being raised in the traditions of past generations.

“On a scale of 1 to 10,” he said, “the old ways are better, hands down.”

He feels marriage has been easier for him and Cynthia because they hadn’t formed independent minds or their own identities before they married.

“We formed our identities together,” he said.

Eng’s son now manages the Cathay Inn. Eddy and Cynthia have lots of time to enjoy each other’s company.

His philosophy of marriage is simple.

“We accepted the roles that God has given us as a man and a woman,” he said. He believes there’s no room for selfishness in marriage.

“I live for her, and she lives for me,” he said. “We don’t live for ourselves.”

And across the table, Cynthia smiled.