Scientists fight for remains

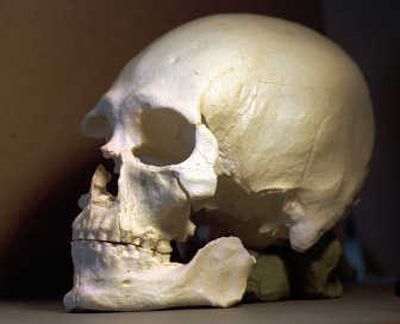

WASHINGTON – Scientists hoping to study the ancient skeleton known as Kennewick Man are protesting efforts on two fronts that they say could block them from examining one of the oldest and most complete skeletons ever found in North America.

For the third time in four years, the scientists oppose a Senate bill that would allow federally recognized tribes to claim ancient remains even if they can’t prove a link to a current tribe.

They also are contesting draft regulations issued by the Bush administration on disposing of culturally unaffiliated remains.

Both measures could end up with the same result, scientists say: preventing an improved understanding of North American history and the role of the continent’s first inhabitants.

If adopted, the proposed changes could “result in a world heritage disaster of unprecedented proportions” and “rob our descendants of the unique insights concerning the shared heritage of all people that physical anthropological studies of culturally unidentifiable human remains can provide,” the American Association of Physical Anthropologists said in a statement.

Supporters call such concerns overblown.

They say the changes are intended to clarify the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, to ensure that federally recognized tribes can safeguard the graves of their ancestors.

Neither the Senate bill nor the draft regulations would affect the 9,300-year-old bones known as Kennewick Man, they said. The skeleton was discovered in 1996 along the Columbia River near Kennewick and has been a bone of contention ever since.

A federal appeals court ruled in 2004 that scientists can study the ancient bones, and teams of anthropologists and other analysts have begun poring over more than 300 bones and bone fragments at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle, where the remains are housed.

A spokesman for Sen. Byron Dorgan, D-N.D., chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, said the Senate bill would clarify what process should be followed for future discoveries of ancient remains.

“The court ruling said it’s not clear” what should happen, “so Congress wants to clarify what its intent was – and its intent is that tribes that believe they have a connection (to ancient remains) either through descent or cultural affiliation, have an opportunity to make that case,” said Barry Pyatt, a Dorgan spokesman.

The Bush administration opposes the Senate bill, which mirrors legislation proposed in 2004 and 2005. In testimony before the Indian Affairs Committee in 2005, Paul Hoffman, a deputy assistant interior secretary, called the proposed change too broad and said it would loosen the Indian graves law to include remains that might not be connected to a tribe.

“We believe that NAGPRA should protect the sensibilities of currently existing tribes, cultures, and people while balancing the need to learn about past cultures and customs,” Hoffman said. In cases where remains are not significantly related to any existing tribe, people or culture, they should be available for appropriate scientific analysis, he said.

The administration did not testify on the current Senate bill – which was approved by Indian Affairs Committee on a voice vote – but its views have not changed since 2005, said Sherry Hutt, manager of the Interior Department’s NAGPRA program.

“The position that the secretary took at that time … was that science is a good thing, and NAGPRA is not administered to be a death knell to science. That remains our view,” she said.

But scientists said the Sept. 27 committee vote – coupled with the Oct. 16 publication of draft rules on disposition of culturally unidentifiable remains – shows there is a deliberate effort to quietly change the NAGPRA law. The Senate bill was approved without a public hearing two days after it was formally proposed.

The draft regulations and the Senate bill assume that any remains found belong to federally recognized tribes, said Cleone Hawkinson, a founding member of the Portland-based Friends of America’s Past. That includes remains from small bands of people who died out and left no ancestors, and remains of indigenous ancestors to modern-day Latinos, including those who died just a few hundred years ago.

“By changing the definition to include everything found as Native American, NAGPRA automatically applies to everything, before any scientific study. Then tribes can decide if they want to allow study,” Hawkinson said.

Hutt disputed that, saying the proposed regulations were not related to the Senate bill and in any case would not affect Kennewick Man. The regulations have been under development since 2001, Hutt said, calling any relationship between the draft rules and the Senate bill coincidental.

Rep. Doc Hastings, R-Wash., who represents the area where the bones were found, has introduced separate legislation to block the Senate measure.

“The quiet Senate effort to extinguish scientific research has to be challenged, and my bill makes it absolutely clear that ancient remains should be studied,” said Hastings, whose bill would clarify the Indian graves law to specify that it was not meant to apply to remains as old as Kennewick Man.

Rob Smith, a Seattle lawyer who represented a group of Northwest tribes in the Kennewick Man case, said the Senate bill would not “allow Indian tribes to make wild claims to any newly discovered remains,” as opponents contend. Tribes still would have to prove a cultural connection with the remains.

“The amendment simply makes it easier for NAGPRA to apply in the first place,” he said.