Bill would limit landlords’ liability

OLYMPIA – Evicted from her Spokane home a couple of weeks before Christmas in 2003, 81-year-old Irene Parker saw her belongings – a bed, four chairs, pet food, dishes, flower pots – hauled out of the house and stacked at the curb.

As she returned over and over that day, the pile shrank, presumably from passers-by carting things off.

With the help of Gonzaga’s University Legal Assistance, Parker sued her landlords, and last month – appealing an initial loss – she won. A three-judge appellate court said that her landlords had a duty to store her belongings. Her lawyers value the missing items at $15,000.

That ruling has spooked landlords across the state, raising the prospect that they may be liable for loss or theft when – as has long been common practice – they toss the possessions of evicted renters to the curbside. Now, worried about two years’ worth of potential claims for lost property from people they’ve evicted, landlord groups want state lawmakers to protect them from that expensive liability.

Legislation inching its way through the Capitol this year would make it clear that while landlords could choose to store evicted tenants’ property, they are under no obligation to do anything other than simply deposit the belongings on the nearest patch of public property. Most of the time, that’s a sidewalk.

Eric Stevens, a Spokane attorney whose entire workload consists of evicting people, said landlords shouldn’t have to risk shouldering the cost of boxing, moving and storing an evicted tenant’s belongings.

“What this means is ultimately we’re going to have increased rents,” Stevens said of the court ruling. “This is a gigantic problem.”

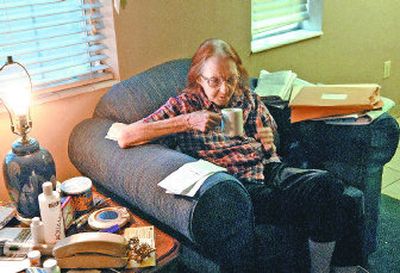

Parker, now 84 and living in a converted motel in Airway Heights, says her problems began with repeatedly unanswered requests for repairs to the small Augusta Street home she was renting in Spokane.

The backdoor lock broke, she said. Phone jacks didn’t work. A large family of cats kept clambering in through a hole in one wall.

After three months of that, Parker said, she started withholding rent from her landlords, a Gig Harbor couple named Glenn and Kim Taylor. A court eventually ordered Parker to pay $1,210. Nearly a month after the court’s deadline, Parker wired $1,000 to the landlords.

It was too late. The following morning, her landlords showed up at the home, along with a sheriff’s deputy. He ordered Parker off the property. She took a cab to a friend’s house but was unable to carry off her furniture or to pay someone else to do it. In addition to the possessions piled up at the curb, she said, she never recovered any of her clothes, a rented washing machine she’s still paying for, kitchen items or anything else.

Ten months after she was removed from her home, Parker sued the Taylors for not storing her belongings until she could retrieve them. There’s no way to account for the sentimental value, she said. Among the things that are gone: her mother’s wedding and engagement rings, her parents’ marriage license and photo albums with pictures of her parents.

“I don’t know what they’ve done with them,” she said. “They’re gone, is all I know.”

She hadn’t moved her belongings or herself, she said, because she still thought the Taylors were going to fix the problems. The Taylors, who had no attorney in the Superior Court case, did not return a call seeking comment.

Spokane Superior Court Judge Salvatore Cozza initially threw out Parker’s lawsuit, saying the law doesn’t require landlords to store evicted tenants’ belongings.

But last month, an appeals court reversed that decision. The law “creates a landlord duty to ‘store the property in any reasonably secure place’ ” unless the tenant objects, the appeals judges said.

It’s one thing, they ruled, if a tenant vacates the home or apartment and leaves some things behind. In such a case, the renter “may be presumed to have taken the belongings he or she desires,” the appeals court said. But it would be a mistake to assume the same thing in so-called writ of restitution cases like Parker’s, where police are brought in to physically remove a renter.

Rep. Brendan Williams, D-Olympia, is the prime sponsor of House Bill 1865, which would make it clear that while landlords may store evicted tenants’ goods, they don’t have to. It would be enough – as landlords and sheriffs have long believed – to simply put the belongings “on the nearest public property.”

“And the public place, of course, is the sidewalk?” asked Rep. Pat Lantz, D-Gig Harbor.

“It could be the sidewalk,” said Williams.

Williams said he’s sympathetic to renters, but that “evictions don’t occur at the whims of landlords, and they don’t occur overnight.” At a bare minimum, Stevens said, an eviction takes 17 days and repeated notices to tenants.

Proponents of the bill also say that landlords wouldn’t necessarily be doing tenants a favor by storing their stuff. The law allows landlords to require repayment for wrapping, boxing, hauling and storage, and that may just be another unpayable bill for someone who already can’t make rent, they said.

Also, they say, tenants typically get their valuables moved once it becomes clear that eviction is imminent.

“About half the time we get there, the people have just left and left some garbage behind,” said Joe Gaddy, a King County sheriff’s detective.

“It’s not uncommon for tenants to leave ratty old couches that they have absolutely no intention of coming back for,” said Stevens.