heartfelt gift

As far as Kathy Cochran is concerned, she received the best valentine of her life last November, from a man she never met.

And her husband, James Mehling, agrees.

Married 18 years, the Mead couple figure they’re able to celebrate together today only because of the final act of a Northwest auto-body repairman named Bob.

Or more precisely, Bob’s family, who chose to donate the heart that now beats in Cochran’s chest.

“It’s hard to wrap your mind around it,” said Cochran, a 43-year-old former social worker and mother of two. “You’re so grateful and so overwhelmed by the gift of love they gave.”

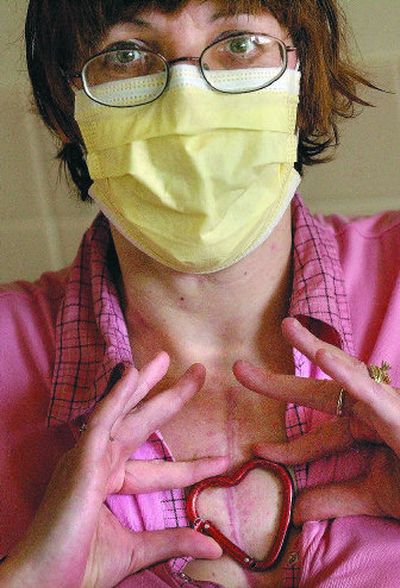

Cochran, wearing a yellow face mask against infection and a pink top that slightly revealed her 10-inch scar, agreed to discuss what it means to live with the literal gift of a heart on this day of mostly symbolic sentiment.

“Your life isn’t your own anymore,” said Cochran. “When they give that, unknowing, they give in faith, hoping that you’ll do right to honor that donor.”

There’s a lot riding on Cochran’s new heart, which replaced an organ diseased by cardiomyopathy – or weakness – and congestive heart failure.

She’s the recipient who nudged the number of heart transplants over the 200 mark at Spokane’s Sacred Heart Medical Center, hospital officials said.

That makes her something of a milestone in the program that began in 1989 and now posts survival rates that routinely exceed national levels, said Dr. Timothy Icenogle, the 54-year-old cardiac surgeon who directs the program.

One of 32 patients died after receiving heart transplants at Sacred Heart between January 2003 and June 2005, according to data released last month from a national transplant registry.

That’s a success rate of nearly 97 percent after one year, compared with nearly 88 percent nationwide, and more than 95 percent after three years, compared with less than 80 percent nationally, according to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR).

By 10 years after transplant, the local survival rate is 72 percent compared with the national rate of 53 percent, Icenogle said.

“Obviously, our survival rates compare favorably to the national averages,” he said.

Icenogle isn’t boasting, however. Survival rates can drop – and do – as they did at Sacred Heart in 1997, the year they lost three transplant patients in a row, he said.

The surgeon, who insists on inspecting potential donations himself instead of leaving it to a junior doctor, said Tuesday he’s acutely aware of the fragility of success in his field.

“I don’t believe in the providence of luck,” Icenogle said. “I believe in mathematical probability and the providence of the Lord.”

Cochran’s transplant was one in a program that averages about a dozen a year. At any time, there are about 45 regional patients awaiting hearts, including the dozen or so local candidates on a paper list that’s updated daily and kept neatly folded inside Icenogle’s jacket pocket.

About half of patients receive a transplant a little more than four months after being placed on the waiting list; nationwide, that same average is nearly seven months, SRTR figures showed.

Cochran was much luckier than most. After three years of medication, operations, a titanium valve, a defibrillator and a pacemaker, she was placed on the waiting list on Nov. 20. A week later, on Nov. 27, she got the call.

“She said, ‘Can you be here in an hour?’ ” Cochran recalled. “I didn’t expect it to go that fast.”

A dozen hours later, a stranger’s heart was pumping in Cochran’s body.

The surgeon who placed it there said he remains no less awed by the 201st transplant than he was by the first he assisted with a quarter century ago.

“We’re always amazed,” said Icenogle, who noted that the most common operating room response is: “Wow.”

“It can be stunning at times even for us who are jaded and old.”

Many transplant recipients never hear from the families of their donors, but Cochran received a two-page letter from her donor’s sister. From that, she learned that he had the same name as Cochran’s father and her son: Bob. And that his sister had the same name as Cochran’s sister: Kim.

The kinship didn’t end there. From pictures, Cochran believes that the 30-ish man, whose death remains a mystery, looks a bit like her oldest boy.

She thinks that the fan of ZZ Top and Creedence Clearwater Revival, a man who bagged his first elk in October 2006, a month before his death, shared the same good humor and sense of adventure that runs through her family.

“You can tell he had that boyish charm, that sense of life,” she said.

Still, all parties in this unusual triangle – donor, recipient and surgeon – remain conscious of the loss that shadows Cochran’s second chance at life.

Bob’s family lost a brother and a son. Cochran gained her life, but at the price of nearly every material possession she once owned – and with medical debt that tallies more than $250,000, even with insurance from her former job as a social worker in Billings and Missoula.

At least twice a week, Icenogle receives the calls that say another heart is available. He personally examines the organ – often selecting those that other programs won’t use, because his experience tells him he can.

And then he puts what he calls this “big risk business” to the test again.

“We have the greatest victories and we have the worst defeats,” Icenogle said.

“When we win, we win big. And when we lose, we create a smoking hole.”