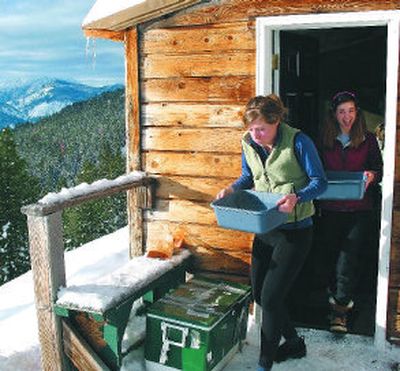

Getting cabin fever

Cabins have been losing their meaning in the past few decades. Instead of a small simple structure providing basic shelter for brief stays, “cabins” have trended toward eyesore mansions infested with all the comforts of home. The biggest pity is that without real cabins, we are deprived of a real cabin experience.

My notion of “cabin fever” has changed from an urge to get out of the house to the occasional need to venture beyond the roads by muscle power, split firewood, melt snow for water, eat by candlelight and draw cards with partners to see who will brave the frosty morning to light the first fire of the day.

A friend shook his head and called me “brave” for joining another dad and skiing six miles into a forest cabin with a group of teenagers this winter. The more I thought about it, the more sorrow I felt for adults who have never had the luxury of being in a primitive setting with young people.

Without cell phones, iPods, computers or TV, even teenagers become human.

They talk to you in complete sentences; they offer to help with chores; they make you laugh; they dazzle with brilliance. They work out issues and help each other through hardships such as blisters and midnight sprints through the snow to the outhouse.

I wish every adult could sample the simple pleasure of eating a long winter meal with a group of young people six miles from the nearest road or electrical outlet. A real cabin has enough magic to bring out qualities that go dormant in city kids.

They’ll relish vegetables.

They’ll manage without a shower or makeup.

They’ll giggle at hat hair and forget about a life packed with schedules.

Teens enjoy the freedom to be enthused about bundling up and heading out into the cold for a moonlight ski. They’ll feed on the group initiative, stamp a trail through the snow, break a sweat and savor a white-cloaked forest so quiet you can hear each other breathe.

With rosy cheeks they’ll return to the glow of lantern light. The cabin brightens as their hats and jackets are hung around the walls and the shelter listens to their stories of mysterious shadows, screaming descents over tree-stump jumps and other adventures in the night.

The energy fades with the glow of the last log in the stove.

They sleep like bears in winter.

That’s what I call living the high life.