Story of Valley Forge

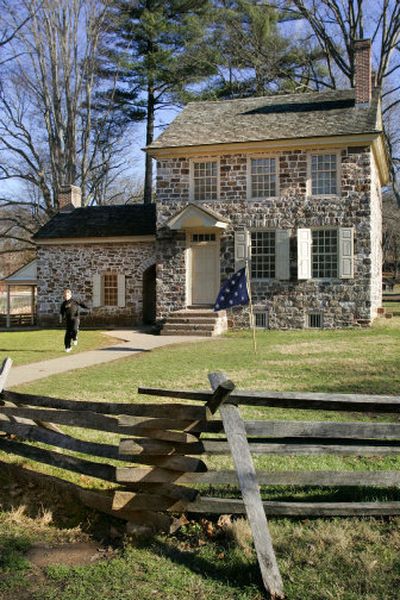

VALLEY FORGE, Pa. – George Washington’s headquarters may be the most important interpretive site at Valley Forge National Historical Park.

The tiny house served as ground zero for planning and coordinating for the Continental Army during its winter encampment at Valley Forge from December 1777 to June 1778.

But officials say the building is hidden in an uninspiring setting, and they’re taking steps to change the way visitors experience it.

The $6 million project is designed to put the story of Gen. Washington back into the home that was the tactical center for his army.

“Now visitors arrive in a parking lot that’s out of context and looks like it belongs in front of a Wal-Mart,” says Deirdre Gibson, chief of planning and resource management for the park. “Then they have to figure out where to go. It’s a confusing experience and one that they often find underwhelming.”

No battle was ever fought at Valley Forge, but it remains a well-known name in American history because of the hard times endured by the troops there. Estimates vary, but most accounts say that 10,000 to 12,000 soldiers spent a cold and snowy winter there amid severe shortages of food and clothing.

Disease was rampant, morale was low, and 1,500 to 3,000 men died. But as winter gave way to spring, food and supplies began to arrive; a mercenary named Baron von Steuben began training the men; and by May, France had agreed to support the colonists’ cause.

The army survived the harsh winter and went on under Washington’s leadership to continue the struggle against the British.

The planned improvements represent the largest single federal investment in the park since it became part of the National Park Service on July 4, 1976.

Changes will start with a new entryway. Visitors will arrive via a rustic road along the Schuylkill River and walk down to the site. The large parking lot that first greets them now will be removed.

The train station overlooking the site, built in 1911 by Reading Railroad, is scheduled to reopen in 2008 as an orientation center for the headquarters.

The station will house a multimedia presentation to introduce guests not only to Washington and his headquarters, but to the village of Valley Forge. The spot was carefully picked for the troops as an encampment site because it was a day’s walk from the British troops in Philadelphia, and because it guarded agriculture to the west.

The iron forge that gave the village its name, along with most of the industrial buildings that comprised it, was torn down when a private group bought the headquarters to preserve it as a historical site in the late 19th century.

“A common notion at the time was the best way to commemorate a site was to beautify the landscape,” Gibson says. “But they took it back to something it never was – a few revolutionary buildings in an open landscape. So now when we try to tell visitors about the village, they think, ‘What cotton mill?’ “

Details are still being worked out, but Gibson foresees features like cell phone call-in sites and podcasts around the grounds to educate visitors about the village and headquarters.

The main focus, of course, will be the headquarters itself. The two-story stone building with four rooms, plus a kitchen, was “the Department of Defense of its time,” Gibson says.

Washington rented the house from a private citizen and lived there with 28 of his senior aides, corresponding frequently with Congress by means of couriers on horseback.

“People are stunned at how small and crowded it was,” says Gibson. “It would have been extremely busy.”

Part of the project’s aim is to break the Valley Forge story down into small chunks, so visitors have a variety of traditional and multimedia options for learning history at their own pace.

Especially in the orientation, Gibson says, much of the focus will be on Washington himself.

“Washington’s leadership is really the story of Valley Forge,” she says. “It’s about the way he kept the Army together even when everybody thought it was over.”