Working in high places

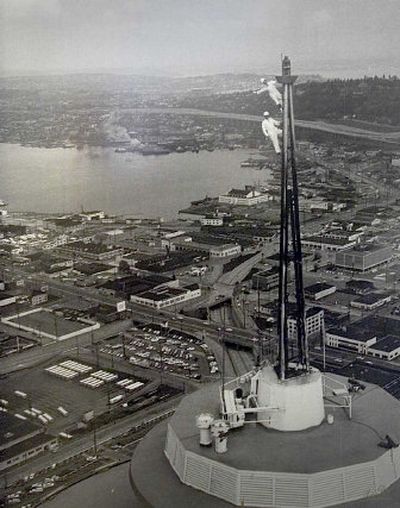

One of the high points in his life, Warren Hinrichs says, was when he and his dad, Bill, had their picture taken on the top of the Space Needle in Seattle by a photographer in a passing helicopter.

Actually, both Warren and Bill had numerous high points in their lives. They both worked as steeplejacks, Bill until he was 73, shortly before his death, and Warren right up to today.

You don’t know what a steeplejack is? Well, many people don’t. (Try finding one in the Yellow Pages.) “My dad used to say it’s a jack who works on steeples,” Warren laughs.

Simply, it’s a person who works on either painting and repairing flagpoles, radio towers, water towers, high bridges and steeples, of course, or any other edifice that most other people are reluctant to climb upon.

“People ask me how high do you go? I tell ‘em how high is the job, that’s how high,” Warren says. He started at 18 right out of high school, working with his father, painting a pair of 200-foot radio towers in Aberdeen, Wash.

“Right after I graduated, my dad asked me if I was ready to go to work. I got $2.50 an hour for that job,” he recalls. “I think minimum wage was like 50 cents an hour then. A pretty good deal.”

Eventually he and his father worked together in a variety of projects and were photographed by a number of publications while at work, including that trip to the tip of the Space Needle.

“He suggested I get on his shoulders for the picture when the helicopter came. Then we were worried about getting blown off,” Hinrichs laughs. “We were 607 feet off the ground. The people below looked like they were on a postage stamp.”

In that era father and son and the Hinrichs family were also featured on the television show “Real People.”

Warren Hinrichs is 65 – he’ll be 66 in March – and not ready for retirement. He’s preparing for his busy time of the year.

He travels in all states west of Mississippi, he says, plus Wisconsin. He avoids big towns, Hinrichs said. “I go to the little towns, where the real people live.”

Hinrich is preparing his state maps with past customers highlighted with colored markers along with the county seats in each state – county seats equal courthouses with flagpoles on top.

Getting jobs is no problem, he says. Word of mouth is important, and “I shake a tree, a nut falls out and I paint it,” he jokes.

He’s a bit more organized than that. He has a record of all of his jobs three years back and many of them will need updating this year. He keeps records of individual clients on 4-by-6 file cards.

Hinrichs is reviewing his logbooks and has “four or five pages of notes” ready for reference when he hits the road, probably in March, with his small dog, a Yorkie cross, as traveling companion.

He’ll go through Southern Idaho first, he said, then drive to New Mexico and the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles and beyond. At the end of August or the first part of September he’ll start working his way back to the Northwest.

“I’ve got a half a dozen jobs in Iowa, three in Missouri, and two in Arkansas,” he says. He zigzags all over states, he says, and studies his maps evenings in his motel rooms.

An outgoing man, Hinrichs obviously enjoys an audience when he’s working and tells of lasting friendships he made throughout the West.

Teachers often bring classes to watch his various projects and he teaches children arithmetic: This pole is this tall and I get $9 a foot, how much is that? And the children get to pick the colors for the flagpole and ball on top. Invariably, the colors turn out to what’s been ordered, he laughed.

Hinrichs sees his work as carrying on a family tradition. His father was a steeplejack for 51 years and he’s been at it 47 years. “That’s coming up on 100 years,” he says..

The late Bill Hinrichs got into steeplejack work because he saw something that intrigued him and then never looked back. He was working as a harvest hand in Minnesota during the Great Depression for $1 a day when he saw a crew painting a water tower in Crosby, Minn. When the crew left for the day, he climbed the water tower, then applied for a job the next day.

“He got hired at 40 cents an hour,” his son recalls. “When they finished the job, the boss said he could travel with the crew if he wanted to and get 50 cents and hour.” Attractive money in 1935.

Warren Hinrichs was born in Colville in 1941, and his father later moved the family to the Aberdeen-Hoquiam area. “Lots of bridges out there, lots of smoke stacks with all those mills,” he says, citing the opportunities for steeplejack jobs.

He recalls that first radio tower job with his father. “Little hook chairs, no safety belts, up to the top, paint on the way down, he was on one side, I was on the other. I was holding on with one hand and he kept painting my glove. I got the message.”

Since that long-ago day, Hinrichs estimates that he painted 4,000 flagpoles. (“Sand and scrape on the way up, paint on the way down.”) Add to that total some 100 water towers.

And he’s proud of his career. “I learned from the best,” he says. “Now I’m the best.”