New Veterans Memorial Museum honors all

It’s a place of bravery at its best. Within the walls of a museum in Chehalis, Wash., American veterans of all wars and from all walks of life are honored in a special way.

Unlike other military museums that focus on the heritage of our nation’s Armed Forces, the Veterans Memorial Museum is all about the individual stories of ordinary people who preserved with their lives the freedoms we have as Americans.

“It isn’t about the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, Coast Guard or National Guard,” says Lee Grimes, founder and executive director of the museum. “It’s about the soldier, sailor, marine, airman and guardsman who deserve remembrance for defending our rights.

“That’s why the museum’s motto is ‘They shall not be forgotten.’ “

Grimes’ journey to open a museum began at his church, where a patriotic program was produced every Fourth of July to honor veterans.

After one production in 1995, a man approached Grimes and his wife Barb to express gratitude. Then he said, “You know, we’re the forgotten ones.”

Hearing that hit Grimes hard and he wondered if all veterans felt that way.

“Within their own little circles at places like the American Legion or VFW, they’re remembered,” he says. “But once they walk out those doors, we don’t know who they are and that really bothered me.”

Three months later, Grimes says, he awoke at 3 a.m. and felt God’s presence prompting him to go out among the veterans and get their stories.

Buying a video camera, he first talked with his wife’s uncle, who was in World War II, then the uncle’s friends.

“These veterans were relieved that someone finally sat down and listened to them,” he says.

Along with stories, personal war artifacts were also given to Grimes, which he stored in his home until launching the museum.The first museum opened in 1997 in a converted 2,000-square-foot electrical warehouse in downtown Centralia. It quickly outgrew the space, so a fund-raising campaign was launched in 2000 for a new facility.

By the time the 20,500-square-foot Veterans Memorial Museum was completed in July 2005, the $1.4 million construction cost was paid in full.

“That in itself was a miracle,” Grimes says.

The first room you see beyond the entrance is the USO, a place of tables and chairs, cookies, cupcakes and coffee, where veterans and family members gather during the day. Visitors are welcome to sit and hear their stories.

“We always have vets in here because if feels safe,” Grimes says. “It’s like a second home to many, especially those whose spouses are deceased, to be with others who served beside them.”

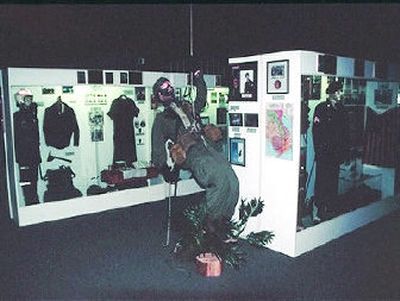

Just beyond the USO, the Main Gallery makes you pause, a sense of reverence filling the vast room. Except for the soft voices of veterans giving guided tours, the Gallery commands a respectful silence.

“This is both a sacred hall and a hall of tears,” says Grimes. “Everyone who serves our country, the ones who survived war and the ones who died in battle, deserve our tears. Within these walls they’re tears of honor.”

Beginning with the Revolutionary War, displays line the aisleways, visual narratives from past conflicts up to the present war in Iraq. Though the nation’s earliest wars lack personal testimonies – those start with World War I – there are uniforms and weaponry, including a large collection of guns sectioned into those used by Americans, British, Germans, Japanese and Russians.

From World War I, there’s a three-star flag dated 1917 – each star representing one son in the service – with a mother’s handwritten prayer: “Three sons I’ve sent off to this war, there’s no more that I can give, Jesse’s star is now of gold, please Lord let the others live.”

A display on the sinking of the British ship H.M.S. Tuscania in 1918, with American troops on board, details the rescue of eight men from Lewis County (where the museum is located) – including Harry R. Truman, who later died during the 1980 volcanic eruption of Mount St. Helens. With the stalwartness of a soldier, he refused to leave his cabin on the mountain.

The World War II section offers numerous profiles of courage. Two soldiers from that war each have a special room named for them at the museum.

The library is dedicated to Laurence Mark, an historian by profession and Army infantryman who fought in the Battle of the Bulge. He also had a brother in the Army who was killed in Korea, his body never found.

The Stan Price Viewing Room – with more than 500 videotapes of veteran interviews and documentaries – honors a man who was captured by the Japanese at Bataan and was a prisoner of war for three and a half years. Though he endured and witnessed many atrocities at the hands of his captors, one Japanese guard helped him and other POWs return to American troops at the end of the war.

Other World War II tributes are given to women who served as Army WACS and WAFS, Navy WAVES, Marine MCWRS and Coast Guard SPARS, plus those in the Red Cross and Cadet Nurse Corps; to Native American code talkers; and to the four chaplains – one Jewish rabbi, one Catholic priest and two Protestant ministers – who went down with the U.S.A.T. Dorchester in 1943, arms linked and praying.

The tears flow on through Korea and the Cold War to Vietnam. In 1968, Jim Kinsman from Onalaska, Wash., saved the lives of seven men by jumping on a hand grenade. Suffering severe head, shoulder and chest wounds, he survived because of a flack jacket and received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Then there’s Doug Houghton, the grandson of a World War I vet, who never received a warm welcome home from Vietnam.”When Doug saw his uniform and pictures encased behind glass, he started crying,” Grimes says. “He told me that the last time he wore his uniform, he was spit upon at the airport when he arrived home in 1968. He never believed he would be honored for service to his country. Finally, he was being thanked.”

Before leaving the gallery of gallantry, you’ll pass by the 30- by 60-foot American flag from the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln hanging above the last display – a moving memorial to the 90,000-plus POWs and MIAs who never came home.

Outside the museum, next to vintage war vehicles, the Wall of Honor has hundreds of tiles with names of veterans, both living and deceased, that families can purchase with money going to the museum’s Endowment Fund.

Grimes is not a veteran himself, though several of his family members have served. But he was recently made an honorary member of the 50th General Hospital, a medical unit that served in France during both World Wars as well as the Gulf War.

“I was told that they were healers of the body,” he says, “and I was a healer of hearts.”