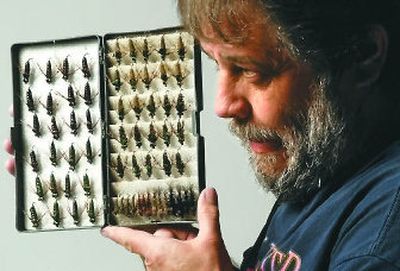

Fly tyer’s effort emerges

Hen-pecked for a couple of decades, John Newberry of Chewelah has finally been freed to find peace and honor from the art of fly tying.

Newberry, 51, recently was named the inaugural member of the Washington Federation of Fly Fishers Fly Tying Hall of Fame. Twenty years ago, he might have had trouble finding the time to go to Ellensburg to accept the plaque.

“I took up fly fishing in 1977 and then I started tying flies in 1978 because everybody said it was cheaper to tie your own,” he said. “Maybe it is, for some people.”

But not for a man who became fascinated by art from beginning to end.

“I got into raising the birds for feathers,” he said. “I mean I really got into it. At one point I had 37 different varieties of pheasants alone, not to mention the peacocks and everything else.”

At the peak of his obsession, the feather purveyor said he was hauling 300 pounds of feed a day to nourish more than 3,000 exotic game birds from all over the world.

“My monthly feed bill was $1,200,” he said. “I finally realized I was working for 17 cents an hour.”

Life is calmer now that he’s whittled down the flock to a more manageable 35 peacocks of three varieties and a few other colorful birds. All are bred for producing hackles that ride dry flies high in the water or wiggle and pulsate beneath the surface as realistically as the legs of aquatic creatures.

Virtually everything a fish eats can be imitated in excruciating detail by fly tying artists who fashion fur and feathers with a meticulousness rivaling the Creator’s.

Find a comfortable chair and gather snacks for sustenance if you’re going to ask Newberry about his craft.

“Look closely at this sand shrimp,” he said, bringing the four-inch pattern close enough to my nose to verify it wasn’t real. “I pulled apart a real sand shrimp to see how it was put together before I came up with this. See how the hackle quills wiggle?”

Like all fly tiers, Newberry borrows from the work of nature and the work of other fly tiers to concoct his own patterns. He created the Wiggle Damsel and Peacock Spider patterns in 1985. More recently, he came up with the Erv Emerger, a tandem caddis pattern he named for the man who introduced him to the fly fishing for big rainbows in the Columbia River.

“I started fishing there in 1982, and I consider it my home water,” he said.

The challenge came after a frustrating day of fishing for finicky rainbows that seemed to be attracted to caddis on the surface but taking only emergers in the surface film. He got back home at midnight, pulled out fly-tying books and studied until 2 a.m.

He came up with few ideas and found encouragement from the late Gary Lafontaine who told him, “I think you’ve got something there,” Newberry said.

After refinement, the pattern incorporates a soft-hackle pattern coupled – “hinged” – closely to an Elk Hair Caddis dry fly with a hidden strand of 38-pound-test steel line.

“The first time I tried it out I caught five fish in five casts,” he said. “One guide beached his boat and walked down the shoreline with a net offering to help me land the fish. Hah. He just wanted to see what I was using.”

Fly tiers try to look at bugs from a fish’s point of view, which is generally from under water.

“You’ve heard of the Traveling Sedges (big, skittering caddisflies) at Whitetail Lake in British Columbia? This floating pupae is deadly up there,” he said holding the fly with its head up and its bottom angling down. “It’s mostly deer hair, but there’s wool at the tail end to make it sink for the proper angle.”

Being the first fly tier inducted into Washington’s hall of fame doesn’t have so much to do with the 65-plus flies Newberry has published on the cover of books and magazines.

“There’s a lot of good fly tiers in the state, but John is always participating, demonstrating skills, sharing information and donating flies to good causes,” said Washington FFF board member Vern Jeremica of Seattle. “He’s a very giving person.”