Wounded soldiers next face legal fight

FORT LEWIS, Wash. – A sniper shot Sgt. Joe Baumann on a Baghdad street in April 2005. The AK-47 round ripped through his midsection, ricocheted off his Kevlar vest and shredded his abdomen.

The bullet also ignited the tracer magazine on his belt, setting Baumann on fire.

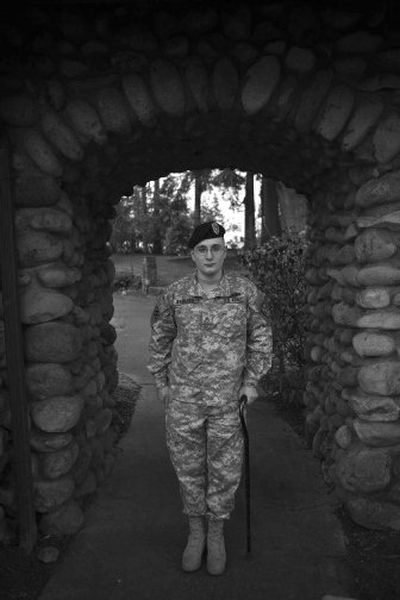

Almost two years later, the 22-year-old California National Guard soldier walks with a cane, suffers from back problems and has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder that keeps him from sleeping and holding a job.

“He can’t even go to the grocery store by himself,” said his wife, Aileen, also 22.

The question pending before a military review board here is whether to grant Baumann a military disability pension and health care or cut him an $8,000 check for his troubles.

It is a tense bureaucratic triage faced by thousands of wounded U.S. soldiers as they negotiate their way back to civilian life. If they are rejected by the military disability system, they can try their luck with the overwhelmed Department of Veterans Affairs – another lengthy process with uncertain results.

A 2006 analysis by the federal Government Accountability Office showed that for National Guard and reserves, the process takes much longer and is less likely to result in full disability benefits.

Baumann’s case remains very much in limbo – despite the extraordinary assistance of two of his former commanders, who took time from their civilian careers to come to his aid.

In a preliminary ruling last month, the three-officer Physical Evaluation Board reviewing his case opted for the severance check, rating Baumann’s disability at only 20 percent and characterizing his PTSD as “anxiety disorder and depression.”

If he accepted the $8,000 check, Baumann still would be eligible to apply for disability benefits under the VA. But VA benefits do not include retirement pay, family health care and military post exchange and commissary privileges. In what many soldiers regard as the ultimate Catch-22, if he were accepted by the VA, he would have to pay the Army’s $8,000 back.

“The Army acts like they just want you to get out the door as fast as possible at the lowest possible cost without taking into account how you are going to live for the rest of your life. Here’s your $8,000, you go, just go,” Baumann said.

Maj. Jesse Miller, one of Baumann’s former commanders, who in civilian life is a San Francisco tax litigator for the Reed Smith international law firm, acts as Baumann’s attorney, commuting regularly from his high-rise office to the dilapidated brick building at Fort Lewis where the Army Physical Evaluation Board hearings are held.

“Look, I love the Army,” Miller said. “I wouldn’t do this if I thought he were gaming the system. But from Day 1 in this case I’ve felt that the system was stacked against getting a just and fair hearing.”

Capt. Kincy Clark, a Silicon Valley software executive who was Baumann’s company commander in Iraq, cut short a business trip to Italy to testify at a Feb. 28 hearing. Both men have dipped into their own pockets to help their former soldier. At Miller’s urging, Reed Smith contributed its resources pro bono.

“The system was designed for a peacetime army to ferret out malingerers,” said Clark, “but they haven’t updated it to accommodate the huge influx of wounded soldiers. Sgt. Baumann is no longer physically or, at this point, mentally fit to go to war. I believe he deserves the full retirement.”

Staccato bursts of small-arms training fire sounded in the distance as Baumann talked about his case recently over lunch.

“If it hadn’t been for Capt. Clark and Maj. Miller I would have just taken the check like everyone else,” Baumann said.

Instead, Baumann is one of a small percentage of wounded soldiers who take their case to a formal board hearing where they have the right to counsel.

As recent congressional testimony revealed, the fates of wounded and injured soldiers such as that of Baumann are in the hands of overwhelmed Army Physical Evaluation Boards, or PEBs, located at Fort Lewis, at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio and at Walter Reed in Washington, D.C. Navy, Marine and Air Force evaluations are handled separately.

After lengthy review by a Medical Evaluation Board to determine if the soldier is still fit for service, the Physical Evaluation Board sets the degree of disability for each soldier, from zero percent to 100 percent. A rating of 30 percent or higher means the soldier can receive military disability retirement. Anything under 30 percent is settled with a check or nothing at all.

Even in seemingly similar cases, determinations vary.

Pfc. Jessica Lynch, the celebrated supply clerk who was taken captive during the initial invasion of Iraq in 2003, was granted 80 percent disability for her extensive injuries, including two spinal fractures and a shattered right arm. But fellow prisoner of war Spc. Shoshana Johnson, who was shot in both ankles, received a rating of 30 percent.

According to the Army Physical Disability Agency, 90 percent of soldiers accept the boards’ initial rulings, forgoing their right to a formal hearing.

Rep. Betty McCollum, D-Minn., who sits on the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, which heard some of the Walter Reed testimony, contends that soldiers suffering from PTSD or traumatic brain injuries might not be fully capable of making such a choice.

“Once they sign that document, they’re making a fundamental decision that will affect them for the rest of their lives,” McCollum said. Other critics note that soldiers are trained to follow orders, not to objectively review decisions made for them.

Some veterans groups say that, faced with unanticipated high casualties, the boards are increasingly guided by budget considerations.

“The Army is shortchanging soldiers by assigning lower disability ratings than they deserve. In some cases, the Physical Evaluation Board misinterprets, reinterprets or even disregards the Medical Evaluation Board findings,” said David E. Autry, deputy national director of communications for the Disabled American Veterans organization.

Army officials acknowledge the increased wartime caseload but say they are doing their best.

“Our cases are now tougher – they are more complicated – as a result of the types of injuries soldiers are sustaining from combat operations,” said Brig. Gen. Reuben D. Jones, commander of the U.S. Army Physical Disability Agency.

Jones said the military disability agency is “currently reviewing how we do our business to better serve the soldier.”

All of this is little solace to Baumann and others as they make their way through the process.

After the Feb. 28 formal hearing at which two psychiatrists testified by phone about Baumann’s PTSD and Capt. Clark testified in person, the board sent Baumann back to the Madigan Army Medical Center hospital for more evaluations.

Miller hopes the medical review will boost Baumann’s disability rating above the 30 percent he needs for full retirement.

“Things seemed to go well in the most recent medical examinations,” Miller said. “I’m hopeful they will make the right decision.”