Lives, campaign clouded by cancer

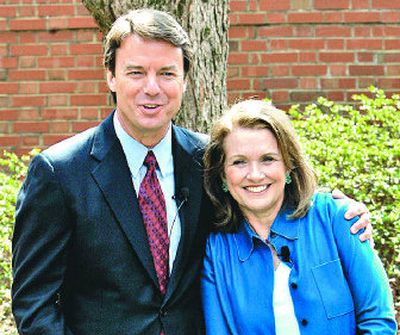

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – John Edwards on Thursday stood beside his wife, Elizabeth, at the site of their wedding reception 30 years ago and said some of the most painful words a human being can utter: “Her cancer is back.”

With that, the 2008 presidential campaign entered uncharted territory: A leading candidate will continue to live the public life of trying to win the White House while enduring the personal ordeal of watching his wife battle a deadly disease.

Thursday’s announcement, at an inn near the university campus where the couple met as law students, provided a glimpse of complex emotions while sparking a debate over whether the couple should focus their energy on fighting the disease or remain in a grueling, around-the-clock campaign that can exhaust even the healthiest participants.

The Edwardses – who were upbeat during their news conference but choked up at points – surprised many people when they announced that the campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination was not over.

“It goes on strongly,” said John Edwards, a former senator from North Carolina. “From our perspective, other than sitting around feeling sorry for ourselves, there was no reason to stop.”

The couple tried to strike an optimistic tone, even while revealing that Elizabeth Edwards’ cancer – first diagnosed in 2004 – had spread from the breast into her bone, indicating it was no longer curable. “Elizabeth will have this as long as she is alive,” John Edwards said.

But, he said, the illness is treatable. “And many patients in similar circumstances have lived many years undergoing treatment,” he said.

Many in the political world – and in the large community of people whose lives have been touched by cancer – responded with an outpouring of emotion.

Laura Farmer, a breast cancer survivor, said she wept while watching the televised news conference from her office in San Diego.

“She’s a role model for coping,” said Farmer, a spokeswoman for Susan G. Komen for the Cure, a breast cancer foundation.

The campaign sent out an e-mail Thursday afternoon indicating the couple still planned to attend a fundraiser this evening in Los Angeles. The candidate also was expected to stick to plans to attend two fundraisers Monday in the San Francisco Bay Area.

But the long-term political implications are uncertain. His wife’s illness may engender sympathy and add an element of human interest to Edwards’ campaign. But there is a risk: Some voters may regard his presidential bid as a misplaced priority, especially if his wife’s condition deteriorates.

Peter Hart, a Democratic pollster, said Edwards will have to strike a “delicate balance … between a loving husband and an ambitious politician.”

What’s more, Edwards’ campaign will be colored by the progress of his wife’s disease. Having promised on Thursday to be with her “any time, any place” that she needs him, Edwards may have to make long detours home from the campaign trail.

Rep. Lois Capps, D-Calif., whose daughter died of lung cancer seven years ago, said she was surprised to hear Edwards say he would continue to campaign. But at the same, she said, it was in keeping with Capps’ own decision to pour back into legislative work after her daughter’s death.

“You retreat or get going with renewed vigor,” Capps said. “I decided to roll up my sleeves.”

While Edwards is not the first politician to cope with cancer or other grave illness in a loved one, Thursday’s announcement marked novel territory for presidential candidates, who already are putting severe strains on family life – and on their own health – by deciding to run.

One Edwards strategist, Dave Saunders, said the couple’s news only motivated him to work harder. “Suddenly I went from 80 miles per hour to 200 miles per hour,” Saunders said.

Saunders said Elizabeth Edwards likely was a driving force behind her husband’s decision to remain in the race. “I know Elizabeth well enough to know that the last thing she would ever want is for John Edwards to step out of a race for her,” he said.

The couple’s news conference, televised near the University of North Carolina, provided voters with a fresh glimpse of an especially close political couple who already had suffered a well-publicized family tragedy. The couple’s teenage son, Wade, died in a 1996 car accident.

Elizabeth, a former lawyer, is widely considered a great asset to Edwards’ campaign. A close adviser, she is engaging – and can be sharp-tongued and irreverent in television interviews. She recently published a book, “Saving Graces,” about coping with the death of her son and her bout with cancer – a sign that the couple intended to talk openly about the disease during the campaign.

“Almost anything that puts the focus, any sort of focus, on Mrs. Edwards or raises the profile of Mrs. Edwards can only help the campaign, because she’s just fantastic,” said Gordon Fischer, former chairman of the Democratic Party in Iowa, a key early-voting state where Edwards seems to be the front-runner. He described her as “down to earth, smart, funny.”

Elizabeth Edwards had found a breast lump during the final days of the 2004 presidential campaign and was diagnosed with cancer two days after the election. She underwent several months of radiation and chemotherapy.

The couple said the spread of the cancer was discovered Wednesday, two days after Mrs. Edwards injured her back while lifting a heavy chest. She then apparently broke her rib the next day while her husband was hugging her.

They said X-rays, biopsies and other tests confirmed a broken rib, and also that the breast cancer had metastasized, or spread.

The Edwardses seemed remarkably upbeat and relaxed for a couple confronting a life-threatening disease that has ravaged the lives of millions of sufferers and their families. Tanned and smiling, they stood side-by-side in the inn’s manicured garden on a sunny spring day. They wore wireless microphones, avoiding the need for a more formal podium in order to address the bank of cameras and reporters that descended on the college town.

“As you can see, I don’t look sickly, I don’t feel sickly,” Elizabeth Edwards said, spreading her arms. John Edwards said his wife would continue campaigning with him. But he added that he would drop everything and rush to her side, “no matter what’s happening in the campaign,” if she were back home in Chapel Hill and needed him.

Reaction to the news underscored that disease knows no party lines. White House press secretary Tony Snow, who underwent surgery in 2005 for colon cancer, praised Elizabeth Edwards for “setting a powerful example.”

Many Democrats were reluctant to discuss the political implications of the development, regarding it as unseemly.