Hearing set on rehab center

An alcohol and drug addiction treatment center that receives more state money for inpatient treatment than any other center on this side of Washington is moving to Spokane Valley, and a hearing Thursday will give its new neighbors a chance to say what they think about it.

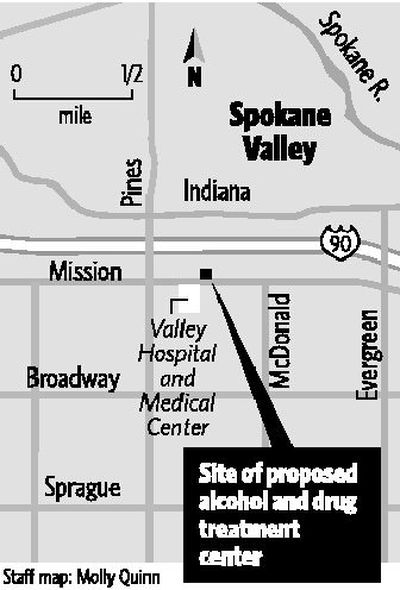

People living near Mission and McDonald have already told city officials they don’t want addicts coming and going from their neighborhood.

But some addicts are already living there.

The company received permission to begin treating people at the site near the Valley Hospital and Medical Center in March, and city officials say they don’t have the legal authority to prohibit it from operating there.

Last year Spokane County commissioners declared American Behavioral Health Systems an “essential public facility,” a designation under state law used to help find locations for things like jails and airports that usually meet with resistance from neighbors.

After public hearings, the commissioners recommended three potential sites for ABHS to expand its operations, with the former Good Samaritan nursing home on Mission at the top of the list.

“The only thing left for us to decide was what conditions to impose,” said Spokane Valley City Attorney Mike Connelly.

The city’s hearing examiner will take testimony to that end Thursday and determine if the company needs to install things like fences or other improvements to reduce its impact on the surrounding community.

The conditional-use permit at issue would allow up to 200 beds for inpatient substance abuse treatment.

The private company can operate up to 50 beds before the permit is granted, according to an agreement in place between the city and ABHS.

The facility accepts both local and out-of-town patients. Most are referred through state agencies, and the company receives $40 to $90 per day from the state for their treatment.

Some enter treatment programs through the courts.

“What we’re worried about is these guys wandering around,” said Roy Basler, a neighbor.

The building is not locked. Patients are free to leave if they want to, which Basler said will create safety concerns for older residents and children at bus stops a few blocks from the center.

The limited liability company also has a checkered past when it comes to running its 117-bed treatment center in north Spokane.

In 2000 the Department of Health took steps to revoke its license after numerous complaints that patients were living in objectionable conditions and that their basic medical and nutritional needs were going unmet.

Last fall the company again was accused of mistreating patients and discharging people rather than tending to their medical needs.

Another state investigation did not substantiate a number of those allegations, though former employees maintain they are true.

ABHS founder and CEO Craig Phillips said then that his company had done nothing wrong.

Demand for state-funded treatment far outstrips the supply of beds in the state, and the new building will allow ABHS to treat more people.

Phillips has said that the new center would have a minimal impact on the neighborhood, adding that there have been few problems with the treatment center operating in its current location.

The former nursing home where ABHS is moving closed in 2004 after Good Samaritan consolidated its operations at a facility in Greenacres.

A permit was filed in March for the first phase of remodeling there, worth about $100,000.