Beekeepers to the rescue

A honeybee is a little thing, but it is bringing big changes to a village in Kenya, thanks to David and Jamie Ziegler.

During a chance conversation with their guide while on a mud-bound safari last December, the Zieglers learned that honeybees can help lift people out of poverty.

The Zieglers keep bees to pollinate their fruit trees at their place above Cougar Bay.

When their Masai guide, Tumate Olesana, marveled at how quickly a fellow villager had been able to sell two jars of honey, Jamie Ziegler got an idea.

After that trip to Africa, she led a fundraising effort to pay for 10 Masai men to learn how to keep bees with the hope of making money from the sale of honey and of lighting their huts with beeswax candles instead of kerosene.

“A small thing maybe to us but a very big thing to them,” she says.

Jamie Ziegler says she is more appreciative of her life and all she has as a result of helping people who possess very little of the world’s riches.

Like others who travel to Africa, the Zieglers saw the plains of the Masi Mara, teeming with wildlife, and they have the pictures to prove it – a pride of lions, a band of baboons, a rhino and calf. Jamie Ziegler even kissed a giraffe on the nose, and she and David rode camels.

The couple also discovered that at the time they were in Kenya, near the end of the rainy season, the unpaved roads turn to sticky, sucking mud, which sometimes alters travel plans with unexpected consequences.

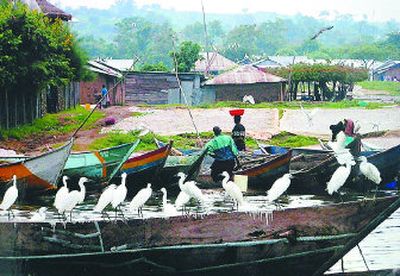

The Zieglers, who visited Lake Victoria, have a picture of their guide and David holding a 20-inch Nile perch he caught.

They also flew to villages where they were greeted by people in traditional dress. For example, they photographed five young, smiling, handsome Samburu women with shaved heads crowned with beaded headdresses and wearing modest, brightly colored costumes.

Jamie Ziegler says one of their favorite places was a small airport in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi – not the international airport.

“There were all sorts of people, native and foreigners,” she says. “You would see produce and crates with live chickens. Walking around in the mix, you would see the tourists all geared up in fancy safari clothes.”

But the Zieglers also saw the dark side of Kenya.

The country suffers from overpopulation – there are an average of 150 people per square mile, and much of the land is arid.

Then there are the slums of Kibera, near Nairobi, with a population of nearly 1 million.

And then there are the AIDS orphans. On Rusinga Island in Lake Victoria, David Ziegler snapped pictures of some of those children, playing in the dusty streets.

“Their grandparents care for them,” Jamie Ziegler says, pointing to the children in the picture. One of every two children in the country has been orphaned by AIDS, she said.

Then Jamie Ziegler points out the metal, windowless buildings in the picture.

“These are the houses where they live – perhaps eight people to a tiny house, and right next door are the metal sheds where they store the sardines, which they caught and dried on nets. Can you imagine the smell?

“These dried fish were to be sold, and the people of the village, as poor as they are, were buying and building, brick by brick, an orphanage for these children who had lost their parents to AIDS,” she said.

“They love their children and value education.”

It was while thinking of these children that Jamie Ziegler had an epiphany.

“That night, on the island, there was a storm with sheets of rain and continuous thunder and lightning that was really frightening,” she recalls.

“But here we were, guests at a resort, in the lap of luxury with everything we might want. I could reach out and flip on the lights if I wanted to.

“And then I thought of the people and children we had seen and talked to during the day in those metal buildings in an electric storm.

“I had thought about my good fortune in life before, but never before had the contrast between those of us who have and those who don’t have been so sharp,” she said. “I have come to appreciate my life more and am more aware.”

In retrospect, that storm and the next downpour seem serendipitous because the foul weather brought unexpected awareness and an opportunity to do something positive and help make a difference.

With the rain-soaked ground turned to gumbo, the Zieglers decided to stay in camp and out of the mud instead of going on safari.

It was then that they had a chance to really talk to Olesana, their guide. He told about a villager who had two containers of honey that he had sold immediately.

Jamie Ziegler thought of her own beehives and knew that they could be the beginning of something good for her new friends in Kenya.

She returned to Coeur d’Alene with a plan to raise enough money from friends, her church and businesses to send some of the villagers to the Baraka Agricultural College at Molo, Kenya. The college, founded in 1974 and owned by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Nakuru, is dedicated to sustainable agriculture.

Jamie Ziegler raised enough money – about $3,500 – to send 10 men to beekeeping class.

She learned the results from Olesana.

It was a life-changing experience for the 10 villagers who went away to college.

They saw more people in one day than they had seen in all their days until then. They saw gas stations, small stores and supermarkets.

In his accounts, Olesana said he was afraid at times the experiment would fail because the students had not been in school since they were 10 or 12 years old. Taking notes was a challenge. He said via e-mail: “It’s a disaster. They can’t stay awake.”

Then, on the third day, he wrote: “In the beekeeping yard, they suited up, but when the bees came out, the men ran away.” After all, these were the notorious African bees. “It doesn’t look good,” said Olesana.

But the men would learn that even these fierce bees can be handled.

On the fourth night, the would-be beekeepers had dinner with regular college students, who told them, “Cattle are your wealth, but bees are income.”

“Coming from their own people who were college students, this meant something. They got the picture,” says Jamie Ziegler.

“On day six, they came, ready to learn.”

What the men learned is that not only would the bees provide income through the sale of honey and wax, but bees also would be good for the environment and increase food production.

Olesana added an e-mail postscript, writing that upon their return home, the men proudly told their wives, “You will be able to burn beeswax candles instead of kerosene lanterns to light the house.”

The family hut, the manyetta, is only about 15 square feet with 6-foot ceilings but is home to as many as eight people, Jamie Ziegler said.

“Can you imagine the smoke from lanterns? On the other hand, beeswax candles burn cleanly.”

According to Jamie Ziegler, the people now have big plans to sell honey and beeswax to their own people and maybe eventually to the tourists who come to the resorts and safari camps.

But for now, the new beekeepers are getting started. Once they establish their hives and the bees have the production of honey up and running, the men will need to return to college to learn how to process the honey.

Jamie Ziegler says she is pleased and hopeful about them, a people she sees as joyful and whom she describes as “having a richness of life if not life’s riches.”