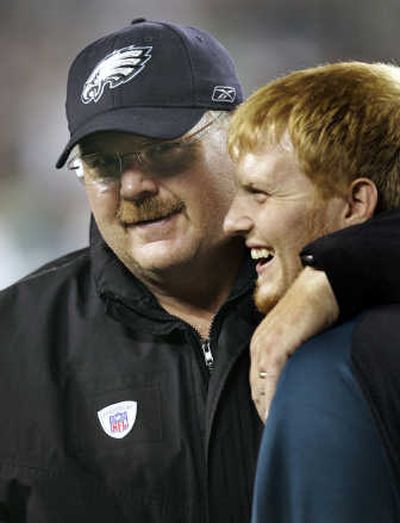

Reid family in dire straits

PHILADELPHIA – As coach of the Philadelphia Eagles, Andy Reid has excelled at keeping the lid on, brushing off questions about team controversies with a countenance as stony as Mount Rushmore.

That lid grew airtight when it came to problems at home, with Reid bolting from briefings when anyone dared to broach his sons’ legal woes.

It therefore fell to a Montgomery County judge last week to publicly reckon with the dynamics of what he deemed “a family in crisis.”

In skewering the structure and supervision in the Reids’ home, Judge Steven T. O’Neill raised the conundrum facing countless other homes in which drug-addicted adult children still live: What is the parents’ responsibility – let alone their ability – to monitor and control their grown children?

“You’ve got to take accountability of what goes on in the house,” O’Neill told Reid and his wife, Tammy, in an extraordinary lecture Thursday at the Montgomery County Courthouse in Norristown, Pa.

His remarks came as O’Neill sent the Reids’ two oldest sons – Garrett, 24, and Britt, 22 – to county prison for up to 23 months each on gun- and drug-related crimes.

The sentencing hearing also laid bare the depths and duration of the Reid brothers’ drug dependencies.

A presentence investigation revealed Garrett Reid to have been a street dealer in North Philadelphia and on the Main Line. Britt Reid’s addiction, the investigation found, began at age 14 with painkillers prescribed after he hurt his back lifting weights at Harriton High School in Lower Merion Township.

He remains addicted to painkillers.

O’Neill reviewed those histories before a courtroom audience already stunned by news that 89 pills had been found that morning in Garrett Reid’s jail cell as he was being brought to court.

Investigators concluded he had concealed them in his rectum before arriving at prison Tuesday evening. He had been ordered there after failing a routine drug test, and now faces additional charges of smuggling contraband.

“I have some real difficulty with the structure in which these two boys live,” O’Neill said, noting the guns, ammunition and assortment of drugs that at various times had been in the Reids’ home and cars. “What is the supervision?”

Mike Wood, a family therapist at the Livengrin Foundation for Addiction Recovery in Bensalem, noted that addicts are very manipulative and creative, good at concealing things. It may be unfair to hold parents accountable for them into adulthood, he said.

“They are adults,” Wood said in an interview Friday. “There is really is no responsibility” on the parents’ part.

A search of the Reids’ home Thursday night – an effort to trace the drugs found in Garrett Reid’s cell – found nothing that had not been prescribed, Montgomery County District Attorney Bruce L. Castor Jr. said.

O’Neill, however, scolded the brothers in court for not taking enough responsibility for their recoveries.

O’Neill suggested that Andy and Tammy Reid, while “loving and supportive,” may have coddled their sons too much. And that their repeated efforts to put the two through drug rehabilitation may have backfired, leaving them dependent on a “cocktail” of prescribed medications.

Using a phrase that dominated the news, O’Neill likened the Reids’ house to a “drug emporium,” where the parents doled out the prescribed daily doses for their sons, who swallowed them blindly.

At Thursday’s sentencing, Andy and Tammy Reid kept the lid on at the courthouse, declining to speak to reporters jamming the halls. But a day later, at his regular Friday news conference, Andy Reid briefly broke his silence.

Without specifically addressing O’Neill’s criticism, Reid said he had “huge concerns” for his sons, and had prayed for their futures.

“This has been a battle we have dealt with here for a few years,” he said, adding that he prayed that “they can live a normal life down the road.”

A normal life – as normal as the grinding, all-hours life of a football coach can be – is what the Reids always said they had sought.

In his early coaching years in Green Bay, Reid would go into the office at 4 a.m., work a couple of hours, and then go home to help get the five kids up and off to school.

Even before entering the pressure chamber of the Eagles, Reid’s time at home was at a premium. As a low-paid assistant coach who never bought on credit, his wife once said, he “worked five or six jobs because he knew I didn’t want to work and wanted to be home with our kids.”

Hired by the Eagles in 1999, the untested Reid quickly built a reputation as an obsessively organized, no-nonsense coach. Reid’s devotion to detail led to many nights on the floor of his office, catching some sleep on sofa cushions.

He built his teams on discipline and tried to draft only players of unblemished character.

The boys were expected to become Eagle Scouts – and Garrett and Britt did so, Tammy Reid said. Piano lessons were required through age 18. Other rules were bent to accommodate the crazy hours of a coach. If her husband “got home at 9 o’clock, you’ll bet the kids are up to see him,” she said.

As Mormons, the Reids did not allow even alcohol in their home. And Tammy Reid has described her husband’s determined efforts to carve out time with Garrett, Britt, and the three younger children – to be present at their sporting events, to take them to movies, to cut down a tree and sing together on Christmas.

Their parents hoped that would be enough.

“There are temptations everywhere,” Andy Reid said in 2001, the year Garrett set off for his father’s alma mater, Brigham Young University. “You hope you raised them right and they take what you’ve given them and try to make sense of it and, once they’re on their own, they can make good decisions.”

Behind the wholesome public image, however, Garrett’s troubles already had started.

Garrett was viewed as the more lighthearted of the two, a comedian who kept things light, like his mother. Britt in high school was more serious, quiet and brooding, spare with words like his father, and disconsolate when his team lost.

By 2000, Garrett had begun selling cocaine, according to his presentencing report, and was abusing drugs and alcohol at 18.

By 2006, he was being treated in a Florida drug rehab facility.

His younger brother first encountered drug addiction at an even younger age, the painkillers prescribed after he cracked a vertebra while lifting weights.

Early this year, the depths of the brothers’ troubles went public on one bizarre winter day.

On the morning of Jan. 30, Britt Reid pointed a handgun at another motorist with whom he had argued while at a stop in West Conshohocken.

About six hours later, a police officer spotted Garrett Reid speeding in an SUV through Plymouth Township, Montgomery County, and gave chase. Reid ran a red light and slammed into a Ford sedan, injuring a 55-year-old woman inside.

When police found drug paraphernalia in the car, Reid admitted using heroin before the accident. Also in his vehicle were a pellet gun and ammunition. Subsequent police searches of the Reids’ home and vehicles found two guns, ammunition and illegal drugs.

The arrests of his sons prompted Andy Reid to take a five-week leave of absence from the Eagles. When Britt and Garrett Reid checked into a Florida drug-rehabilitation program, he accompanied them.

The results have not been stellar.