Libraries try outsourcing

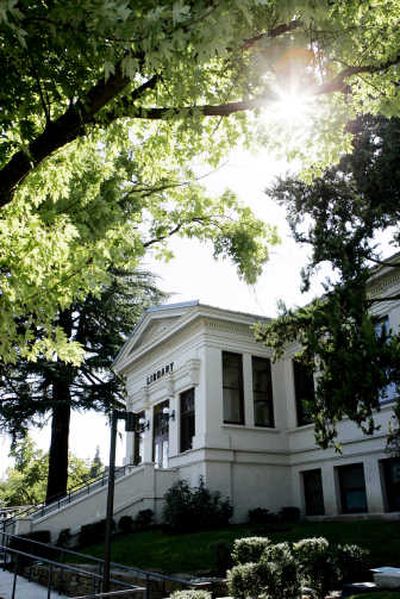

MEDFORD, Ore. – A big, red “Closed” sign has been plastered across the front door of the library here since mid-April, when Jackson County ran out of money to keep its 15 branches open.

In a few weeks, though, the sign will come down and the doors will be flung open again, now that the county has come up with an unusual cost-saving solution: outsourcing its libraries.

The county will continue to own the buildings and all the books in them. But the libraries will be managed by an outside company for a profit. And the librarians will no longer be public employees and union members; they will be on the company’s payroll.

Library patrons might not notice much difference, but the librarians will, since the company plans to get by with a smaller staff and will have a free hand to set salaries and benefits.

“The average citizen, when they walk into the library, they will see well-trained, well-educated, customer-service-oriented people working in the library,” said Bob Windrow, director of sales and marketing at Germantown, Md.-based Library Systems and Services, or LSSI, the company taking over. “They won’t know who is paying their salary, and they won’t care. They care whether the library is open adequate hours, and are they getting good service.”

For years, state and local governments have been privatizing certain functions, such as trash collection, payroll processing and road maintenance.

But contracting with an outside company to run a library is a relatively new phenomenon, one that has been gaining in popularity as communities in states from Tennessee to California look for ways to save money.

The practice has generated a backlash from those who argue that municipalities are employing a backdoor method of union-busting, and those who say that such profit-making ventures go against the notion that libraries are one of the noblest functions of government in a democracy.

“This is a shift from the public trust into private hands,” said John Sexton, an out-of-work Jackson County librarian who has interviewed with LSSI for his old job. “Libraries have always been a source of information for everyone and owned by no one.”

Most of the 15 or so U.S. municipalities that have outsourced their libraries have signed on with LSSI, which is the biggest player in the field but is privately held and does not disclose earnings.

Jackson County lost 36 percent of its budget in one fell swoop last year when Congress failed to renew the rich subsidies designed to help parts of the country where logging has been hurt by endangered-species regulations. Rather than cut back on, say, law enforcement, county officials closed the libraries. (Congress later approved a one-year extension of the logging subsidies.)

Book lovers complained bitterly about the closings, but two ballot measures to raise taxes and reopen the libraries fell short. Then LSSI offered to run the libraries, underbidding the public employees union.

The contract with LSSI will be worth around $3 million a year; the county will also budget $1.3 million to maintain the buildings. Combined, that is about half of the $8 million a year the county previously spent on its libraries.

However, the libraries will be open a total of only 24 hours a week, compared with 40-plus hours for most branches before the shutdown. And LSSI plans to hire 50 to 60 full-time employees, down from 88 under county management.

The county will retain control over certain policies, such as late fees, the cost of a library card or how long library patrons can keep a best-seller.

But LSSI will be in charge of buying books and says it will use its muscle to obtain deep discounts from suppliers. It will also be responsible for hiring, and says that while its salaries will be comparable to what the employees were making previously, the benefits will be less generous. The workers will lose the right to participate in Oregon’s pension system for public employees and instead will qualify for a 401(k) program.