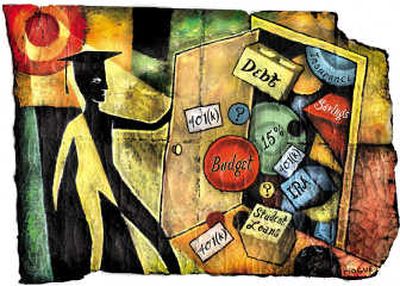

Degrees of difficulty

Worried about getting a student loan?

Some financial aid experts say college applicants shouldn’t fret about recent reports of a student loan crisis.

But they acknowledge that the atmosphere seems scary.

Some lenders have quit offering federal student loans since Congress made that business less profitable last fall by reducing subsidies to lenders of the federally backed loans. And most recently, the credit market catastrophe has left some lenders without the money to make new loans. But, the optimists say, fallback options will protect students.

We asked them to explain.

Q. Recent news reports have said it’s going to be harder and more expensive to get student loans. What’s going on?

A. Roberta Johnson, director of student financial aid at Iowa State University in Ames, says one must first distinguish between federal and private loans.

“I don’t always think that the media is doing a good job of explaining between the two, when the headline says there’s a student loan crisis.”

Depending on the school, federal loans are provided either directly from the government or, more typically, by banks, credit unions and other financial institutions. All are considered federal loans because the government guarantees payment for any lenders providing them.

The most popular student loan is the federal Stafford loan, on which the interest rate is set at 6.8 percent (the rate will fall to 3.4 percent for the neediest students by the 2011-‘12 school year). Students qualify for a Stafford regardless of credit rating.

Because of the government backing, Johnson says, “there should not be a challenge in the federal loan program.”

Incoming freshmen can borrow up to $3,500 in Staffords. Sophomores can get $4,500, and juniors and seniors can take out $5,500. Congress is considering proposals to raise those ceilings.

Separate from federal loans are private loans for which banks and other lenders can set higher interest rates and stricter terms because they, rather than the government, are assuming the risk of a default. With the credit markets slumping, these private loans are the ones likely to become more expensive. And lenders who continue to offer them will be pickier about who qualifies.

Q. If more lenders stop making federal loans, won’t it be harder to get them?

A. Applicants for aid submit a federal form that describes their family finances. This information determines how much college expense students and parents can be expected to bear, and it helps schools judge how much financial aid to offer to help make up any shortfall. Aid packages typically mix grants, loans or work-study jobs.

Eileen O’Leary, director of student financial services at Stonehill College in Easton, Mass., says financial aid officers work to help accepted students pay for their education. If loans are necessary, the advisers suggest federal loans first.

At schools where students take out federal loans from banks or other financial institutions, financial aid staff monitor lenders constantly, O’Leary says. If some quit making such loans, “Any financial aid officer worth his salt should be able to find another lender,” she says.

True, about 50 lenders have stopped making federal loans. But there are roughly 2,000 lenders in the federal loan program and those that remain will fill the demand.

O’Leary says: “We have to differentiate between: Is it a lender crisis? I would say that it is. Or a student crisis? I would say that it isn’t.”

Q. What is the federal government doing to make sure loans will stay available?

A. Robert Shireman, executive director of the Project on Student Debt in Berkeley, Calif., says, “There are good backstops in place to make sure that everyone who is eligible for a federal student loan can get a federal student loan.”

First he cites the direct-loan program, in which the government is the lender. Shireman notes that the U.S. Department of Education is working to increase the availability of that program, which only about a fifth of colleges use now. The rest invite other lenders to make federal loans to their students.

Second, he points to the government’s promise to land federal loans for any students who somehow find themselves without an available lender.

Because the federal government is less vulnerable to market fluctuations than private lenders, it can pick up the slack, Shireman figures. “There is no reason for students to worry about the availability of federal loans,” he says. “They should get ready for college.”

Q. Where does the federal loan fit into a student’s college payment strategy?

A. Luke Swarthout, higher education advocate at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group in Washington, says federal loans complement other financial aid.

Students and parents should compare aid offers from different colleges, considering how much it would cost to attend each school. They should minimize loan debt, says Swarthout, to avoid hauling tens of thousands of dollars in debt into entry-level jobs.

Students who want to attend schools beyond their means should reconsider, maybe choosing a community college at first or a state school, Swarthout says. “There are good, more affordable options.”