Descendant seeks return of artifact

Storied medal has place in Nez Perce history

SPALDING, Idaho – From the rolling Clearwater Valley to New York City’s concrete canyons, a silver medal that may have been given to a Nez Perce Indian chief by Lewis and Clark in 1806 has made an improbable journey.

Its provenance isn’t ironclad, but some historians believe this Jefferson Peace Medal minted in Philadelphia went up the Missouri River, was buried in an Indian grave, later plundered by railroad workers, and eventually landed with Edward Dean Adams, the New York financier and J.P. Morgan contemporary.

Long considered stolen, it surfaced around 2002 in the American Museum of Natural History.

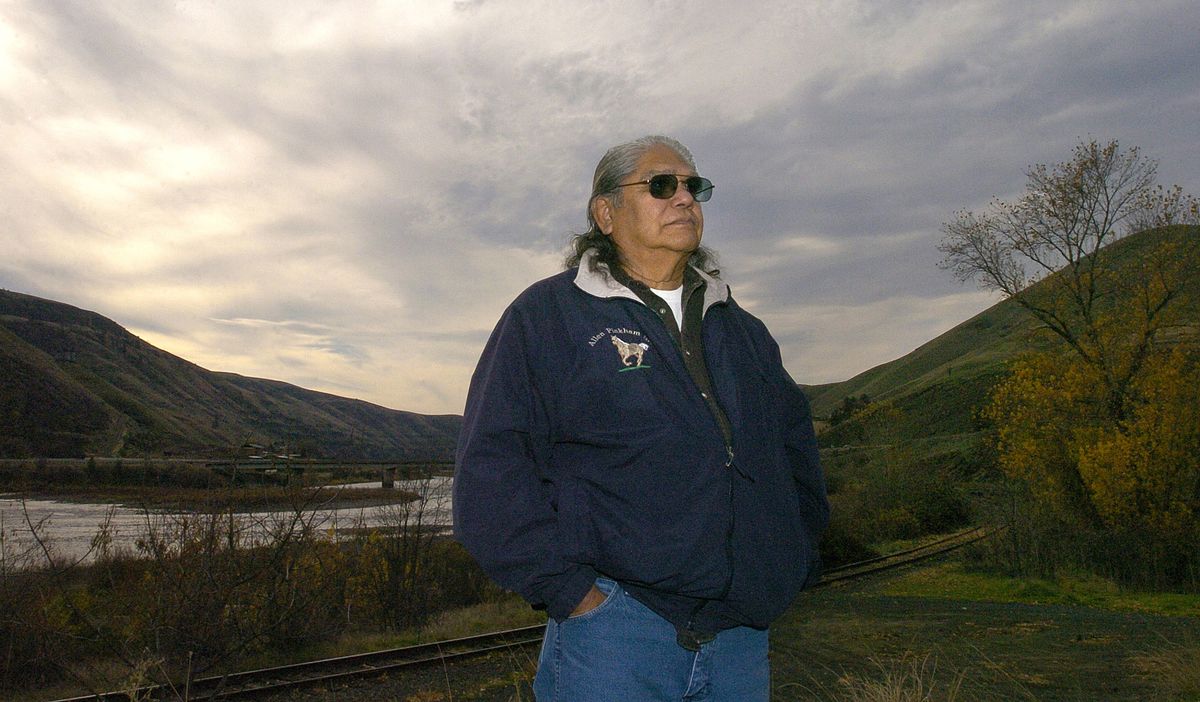

Allen Pinkham, a distant nephew of Cut Nose, the chief believed to have received the medal, is pushing for its return to Idaho. Pinkham sees it as a step in correcting two centuries of injustices since the “extreemly hungry and much fatiegued” adventurers – Lewis and Clark’s own words and spelling – tromped into his great-great-great-great-uncle’s village.

“When we quit stealing from one another, then we become one people,” he told the Associated Press. “This is also part of that recovery.”

Historians say the medal, with President Thomas Jefferson’s image on one side and hands clasped in friendship on the other, is a numismatic Forrest Gump that bore witness to Manifest Destiny in action: the opening of the frontier, the laying of the rails, Edward Adams’ Wall Street – in short, America’s rise to power, and Indians’ fall from it.

“It’s this portal to all these stories,” said Mike Venso, a former Idaho journalist now living in St. Louis who helped trace the medal to museum storage at New York City. When Lewis and Clark departed St. Louis May 14, 1804, they brought about 90 medallions to impart a clear message on the Indians who received them: A U.S. juggernaut spanning the North American continent was rising to replace the French, Spanish and British.

“These objects were very much delivering the message that there’s a new and dominant government overseeing these areas,” said Robert Miller, a professor at Lewis & Clark College in Portland and author of “Native America, Discovered and Conquered.”

After wintering on the Pacific Ocean, the explorers had just entered present-day Idaho when they encountered a Nez Perce village on the Clearwater. Though first unimpressed by its leader, they gave him “a medal of the small size with the likeness of the President,” according to a May 5, 1806, entry describing the scars on Cut Nose’s face, which had come from a lance wound in battle.

Their estimation likely grew – especially after Cut Nose helped bring about the return of a stolen tomahawk that belonged to Charles Floyd, the only expedition member to die along the journey.

In fact, Lewis and Clark’s encounters with Nez Perce like Cut Nose left them with a glowing impression of the tribe, especially after the petty thievery and harassment the exploration party suffered from Indians downstream on the Columbia River, said Gary Moulton, a University of Nebraska historian and Lewis and Clark journal editor.

“In the Nez Perce, they found people that were distinguished, welcoming, generous and friendly,” Moulton said.

In all, the journals mention Cut Nose on 12 dates – including a June 12, 1806, entry describing how the chief borrowed one of the explorers’ horses to capture young eagles to raise for their feathers.

After the June 23 entry, Cut Nose made what under ordinary circumstances might have been his last cameo in documented western U.S. history: He was at an 1834 rendezvous with Protestant missionary Jason Lee, according to the book “The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest,” by Alvin Josephy.

But in 1899, workers building the Northern Pacific Railroad where the Potlatch River runs into the Clearwater some 15 miles east of Lewiston unexpectedly unearthed several Indian graves. Items exposed included beads, a flintlock rifle, rusty hatchets – and the peace medal with President Jefferson’s likeness “carefully wrapped in many thicknesses of buffalo hide,” according to a 1919 railroad history written by Olin Wheeler.

Given the grave’s proximity to where Lewis and Clark put Cut Nose’s village, historians surmise the medal was the one that changed hands in 1806.

“This is the joy and frustration of researching historical objects and history in general. We weren’t there, and the people who were aren’t here. They leave us only little clues,” Venso said. “I believe very strongly that the medal found at the Potlatch River was given by Lewis and Clark to Cut Nose.”

Adams, a railroad president and Wall Street banker featured on the May 27, 1929, Time magazine cover, eventually took ownership before giving the medal to the American Museum of Natural History in 1901, according to the museum’s records.

Pinkham, a former Nez Perce tribal chairman and storyteller, first learned of it around 1998, while serving on the board of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., amid preparations for the Lewis and Clark bicentennial. An anthropologist friend at the American Museum of Natural History told him it had been stolen in the 1930s.

About four years later, however, the same friend had better news.

“He all of a sudden tells me, ‘Hey, we found the medal,’ ” Pinkham said.

Laila Williamson, a museum anthropologist, confirmed this week that the medal remains in storage.

Pinkham has asked tribal leaders to push for its return, possibly under the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, the 1990 law governing American Indian cultural items and human remains.