Too Much Of A Good Thing

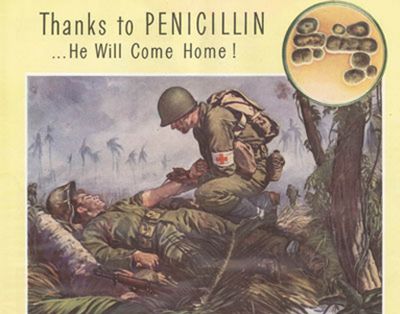

One of the landmark inventions of the 20th century, penicillin and other antibiotics are losing their ability to fight the ever evolving organisms that threaten human life.

The use of antibiotics is a good thing. They have saved countless lives and allowed us to increase our life expectancy dramatically.

Yet the living organisms, the microbes, that antibiotics were invented to battle have been around much longer than humans. Unlike antibiotics, they have the ability to evolve.

In recent years, dangerous microbes have grown more and more resistant to the antibiotics most described by doctors. Sometimes called “superbugs,” these antibiotic-resistant germs are responsible for the deaths of nearly 14,000 Americans each year while making 2 million of us sick, according to World Health Organization statistics.

The main reason antibiotics are starting to lose their effectiveness is human folly. We have too much of a good thing. Doctors prescribe antibiotics routinely, sometimes for viral infections like influenza. Viruses, including the flu virus, do not respond to antibiotics. Another cause for the evolution of antibiotic-resistant microbes is the practice of feeding antibiotics to animals in confined factory meat farms spawning.

When antibiotics are given to living creatures, their systems can only use about 5 percent. The remaining 95 percent is excreted into the environment. Snippets of antibiotic DNA wind up in soil microbes and other bacteria because these tiny creatures “swap” genes, constantly exchanging genetic information and evolving.

A study presented in 2006 to the 106th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology found antibiotic-laced DNA in all water sources tested; from effluent ponds on factory dairy farms, wastewater recycling plants, to drinking-water treatment plants, and even wild river sediments. Amy Pruden, one of the study’s researchers, found the DNA that helps make germs resistant to antibiotics was hundreds to thousands of times higher in water affected by people or factory farms, but still prevalent in smaller quantities in pristine water sources.

A 2001 study by University of Illinois microbiologist Roderick Mackie documented antibiotic-resistant genes in groundwater downstream from pig farms as well local soil organisms that usually do not contain them. His research found that tainted DNA was in bodies, underfoot in the soil, and in the water around conventional feedlots. Mackie noted that soil bacteria around antibiotic-using farms carried 100 to 1,000 times more resistance genes than the same soil bacteria around organic farms.

Making matters worse, feedlots often use their wastewater lagoons to irrigate crops. A University of Kansas environmental engineer noticed a dramatic spike in antibiotic resistant genes living on one Kansas feedlot. He discovered that new calves were given “shock doses” of antibiotics, which they promptly excreted into the lagoons.

That effluent was pumped to the fields to fertilize the cattle feed. They were spraying the crops with highly resistant bacteria from the lagoon, and then feeding it back to the cattle.

Another study of the mouths of healthy kindergartners found that 97 percent had bacteria with antibiotic resistant DNA for four in six of antibiotics researchers tested for. Resistant microbes comprised 15 percent of the children’s oral bacteria, although none of the children had taken antibiotics in the past three months. How the resistant bacteria got past those little lips is cause for much concern. Mackie pulled resistant genes from his deepest test wells, suggesting that the farm’s polluted DNA percolated down toward the drinking water supplies used by surrounding communities.

Another possibility is over-prescription of antibiotics for non-bacterial illnesses, or not taking the full cycle of antibiotics prescribed. The bugs that survive pass on their antibiotic-resistant traits to the next generation, breeding “superbugs.”

Mom’s wisdom is still the best defense:

— A study released in March found standard soap and 10 seconds of scrubbing to be among the most effective ways to get rid of bacteria. With 10 seconds of scrubbing, soap and water gets rid of the common cold virus, hepatitis A, and a host of other illness-bearing germs, the study found.

— Skip the alcohol-based, water-free hand-cleaner, and antimicrobial soaps as they may actually do more harm than good in terms of building up the human immune system, and reducing levels of friendly flora. A better alternative is to get in the habit of regularly washing your hands.

— When your doctor prescribed antibiotics, ask if the infection is bacterial or viral and why antibiotics would help.

— Take the full course of antibiotics that the doctor prescribes, even if the infection disappears and you feel better. Otherwise, the bacteria could evolve resistance to the antibiotic making it ineffective treatment.

— Support small-scale local farms that produce meat using organic practices, and “free-range” or “pastured” methods instead of confining animals (and microbes) to small areas where disease breeds.

Shawn Dell Joyce is a sustainable artist and activist living in a green home in the Mid-Hudson region of New York. Contact her by e-mail Shawn@ShawnDellJoyce.com